Some were quickly produced to make sudden announcements such as the visit of a Japanese dignitary or an imminent medical inspection. Others were long term camp rules and orders concerning behaviour, language, dress and decorum. A few announced an upcoming quiz night, a ‘mock’ trial or a spelling bee. On occasion, these cheerful, brightly illustrated, hand-drawn posters attracted souvenir hunters. On Wednesday 7 October 1942, de Crespigny noted in his diary that the posters were now being covered in wire netting to protect them because ‘someone pinched a copy of the South Africa poster last night – blast them!’

Posters required paper and paper, together with other art and craft supplies such as watercolours, crayons, brushes and paints, were naturally in short supply at the Bandoeng Camp. On Friday 18 September 1942, a corvee (a work party) of prisoners were sent to clear out a large Dutch school.

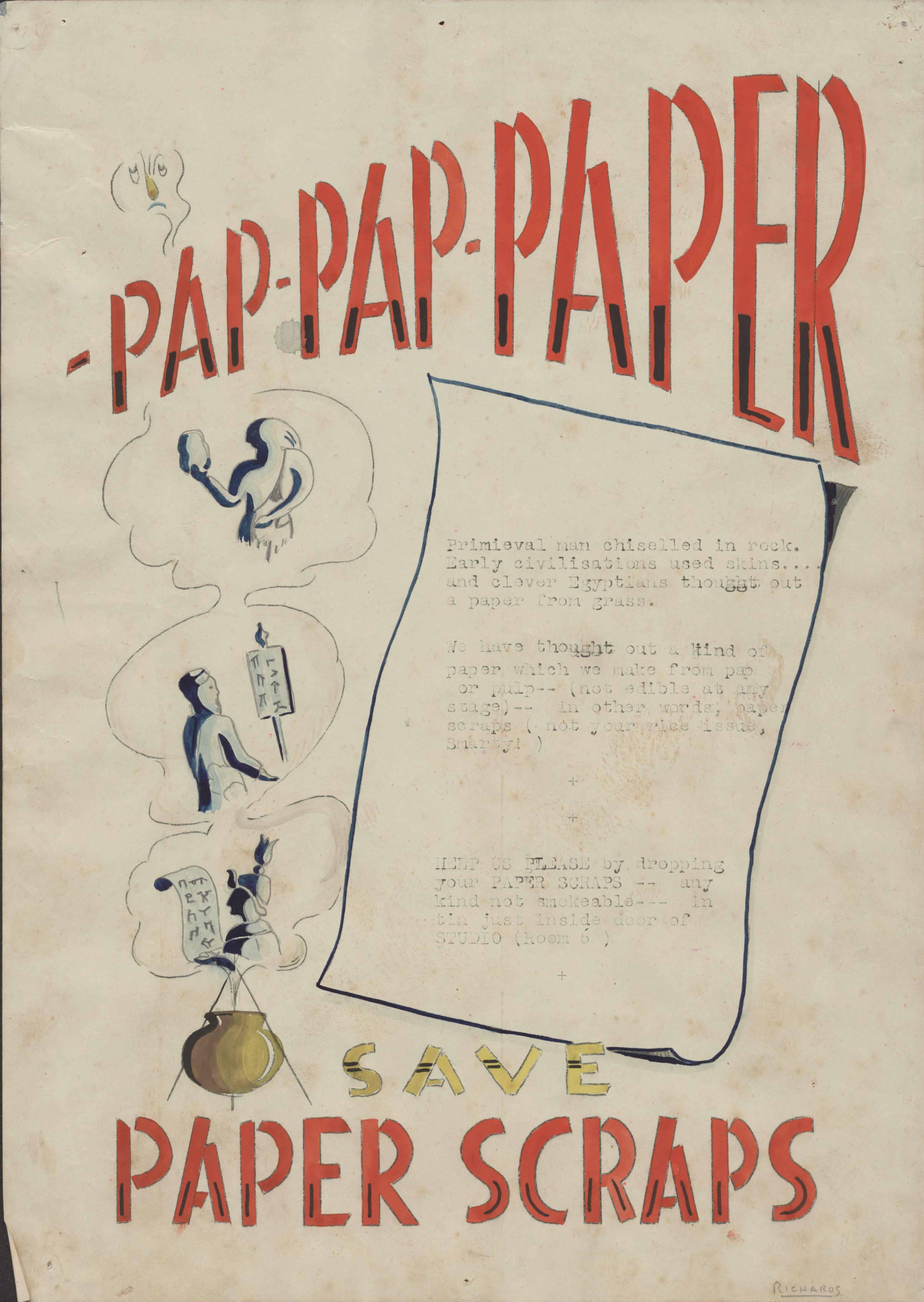

Permission was sought to go and salvage some of the precious materials because there was ‘tones [sic] of it’ - alas, to no avail. For the most part, de Crespigny’s small poster team – made up of Cpl Arthur Bentall, Pte Fred Simpson and Pte Dorando Richards relied on what they could scrounge or find and also upon the generosity of the officer class in purchasing paper and materials on their behalf. In July 1942 de Crespigny was utterly delighted to record that ‘Colonel Van der Post has purchased with his own funds a quantity of pencils, drawing paper, drawing blocks and a box of water colours. Wack ho!’[1] ‘Yet astonishingly there was also a quaintly titled ‘Paper Manufacturing Department’ set up in the camp which made a rough and ready sort of thick pulp paper from paper scraps. On viewing the first batch of the camp made paper, de Crespigny called it a ‘thrilling moment’ and was ‘amazed’ because the paper was ‘excellent’ and ‘success was at least in view!’ With just a little more refinement with rice, a few chemicals and more waste paper he was confident they could continue to improve their ‘local product’.[2] This poster was created to encourage the men to save every last scrap of paper they could find for the ‘pap’ making project.

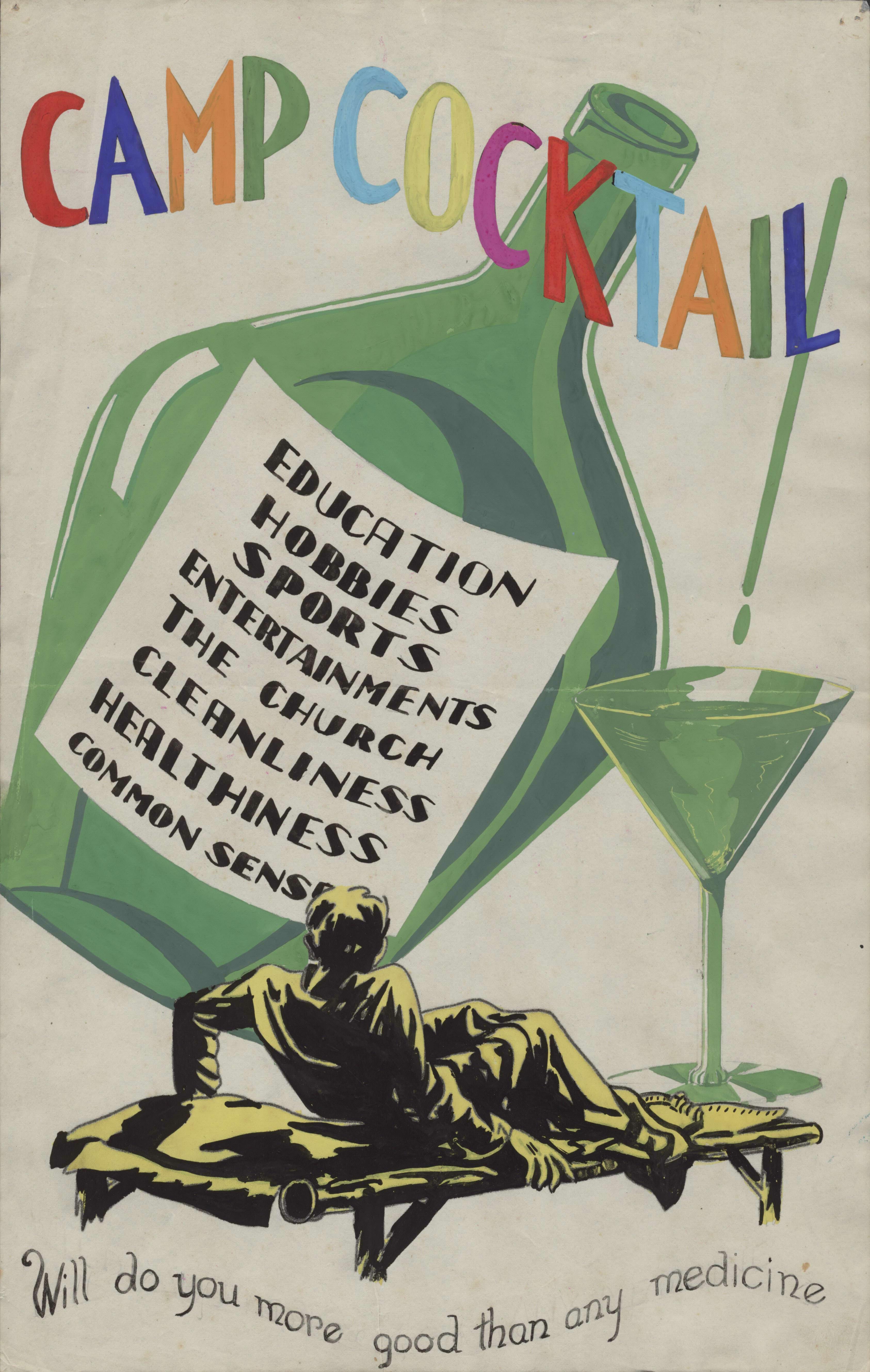

Despite the relative freedoms the inmates at Bandoeng had, they were often made to labour for long hours, morning and evening roll call and parade (tenko) was strict and regular, and there were few comforts to be found in the living quarters for the majority who ranked below the officer classes. More serious however, was the insufficient nutrition the men received as meals were mostly rice (also known as 'pap') boiled with little else but sugar and maggots that had infested the food stores. The paucity of sufficient medical supplies raised the dangerous spectre of contagious diseases, which in such confined conditions might spread like wildfire. Beriberi, pellagra, dysentery and malaria were rife. Boredom threatened mischief, whilst fear might lead to desperate attempts to escape, both of which would be severely punished by the representatives of the Imperial Japanese Army who were guarding the camp. And with scant news of how the war was going and with no international post or Red Cross comforts parcels being permitted into the camp, the mental health of all was of deep concern.

In such potentially explosive and depressive circumstances - posters such as ‘Camp Cocktail’ sought to raise spirits by exhorting the men to keep busy and stay as healthy as possible. Minds and hands could be occupied with classes and hobbies, bodies could participate in the many sporting activities that were available and, as far as possible, all should exercise common sense when it came to habits of health and cleanliness. Religion and Sunday church service also had a significant role to play in fortifying men’s hopes and beliefs for the future. All these activities would ‘do more good than any medicine’ which was possibly an allusion to the fact that there was not much medicine available, if in fact, any at all. We don’t know who created this poster although in September 1942 de Crespigny noted in his diary that he had ‘started the boys off on the Health Posters’.[3] De Crespigny himself was a firm believer in keeping busy, the importance of mental and creative stimulation and the taking of regular exercise. He took great pleasure in watching the inmates of the camp immerse themselves in the lectures, the arts and crafts classes and the sports and entertainment opportunities that had been made available to them. Both individually and collectively, camp activities provided temporary escapism and allowed them all to live ‘as if no barbed wire, guards or war existed.’[4]