Morale was also boosted by having something to look forward to – be it a play, a musical extravaganza, a sports day or the traditional celebration of Christmas. The staging of exhibitions, such as an arts and crafts exhibition involved great planning with the formation of a guiding committee and regular meetings. The very nature of an arts and crafts exhibition also challenged the prisoners to get creative with whatever materials they could find, whilst also affording them a chance to show off any hidden talents they might have.

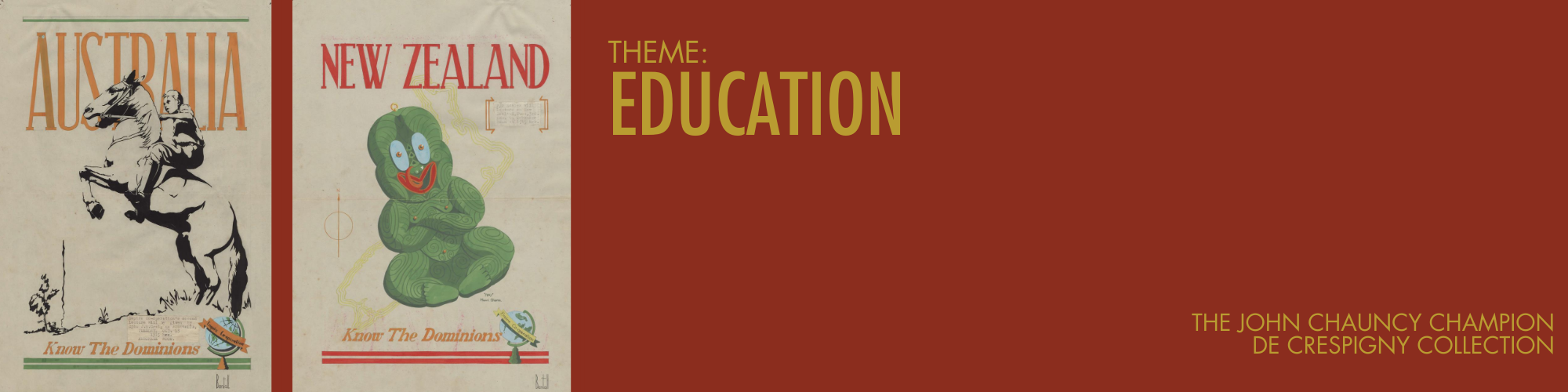

In August 1942, an arts and crafts exhibition was held in the school block at Bandoeng. It was a roaring success. Art, needlework and embroidery, wood and metal carving, model making, sketches, paintings and many other handicrafts were all displayed. The exhibition included work from British, Australian, Ambon, Dutch and Menado contributors and it was greatly praised. De Crespigny was delighted to note that the show had been ‘voted a huge success by the camp’, so much so, that due to popular demand, it was extended for an extra number of days.[1] Plans were tentatively made to hold another one before Christmas. In late October however, unsubstantiated rumours that a ‘move was on’ began to be whispered around the camp. According to de Crespigny, ‘everybody dreads like hell the idea of a move – I am afraid it would mean death to some, they are in such a parlous state of health.’[2] A few days later, the prisoners at Bandoeng learnt that 1000 Australian officers and men were to be relocated. De Crespigny deeply lamented the breaking up of the thriving community of teachers, scholars, artists and creative collaborators. In his diary he mournfully noted, ‘Goodbye Education Scheme, Arts and Crafts, Library, Baseball and all the familiar activities and odd little comforts of this camp.’[3] Yet within weeks of arriving at their new camp at Makasura, Batavia, the men had resumed many of the artistic, educational and theatrical activities which had characterised life at Bandoeng. Another arts and crafts exhibition was held here in early December as a ‘pre-Xmas event’. This time, due to the nationalities of the Makasura inmates, it was a purely Australian and British affair. Having been approached by two British prisoners about holding an exhibition, de Crespigny immediately called a meeting ‘of the old gang’ from Bandoeng to make plans. Enthusiasm was rife and the lads were ‘as keen as mustard’ because it ‘gave them an interest and helps to pass the time’.[4] He immediately set to work crafting this poster to advertise the exhibition (being careful to also make a copy for the Memorial Book.) On Thursday 3 December the show opened and was again deemed a resounding success with a constant stream of visitors throughout the day. ‘Outstanding among the exhibits’ he wrote ‘were models in perspex - a malleable plastic glass used for aircraft windscreens. The articles made of this new material were ingenious and of excellent workmanship. Several wood carvings and a chess board drew considerable attention.’ Lt Col Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop was similarly impressed with the RAF exhibits and the art works

Staying busy and occupied through creative pursuits and finding beauty in the natural world when the daily reality was all rather bleak, gave many prisoners a sense of purpose, a belief in the future and a gentle reminder that where there was life, there was still hope.

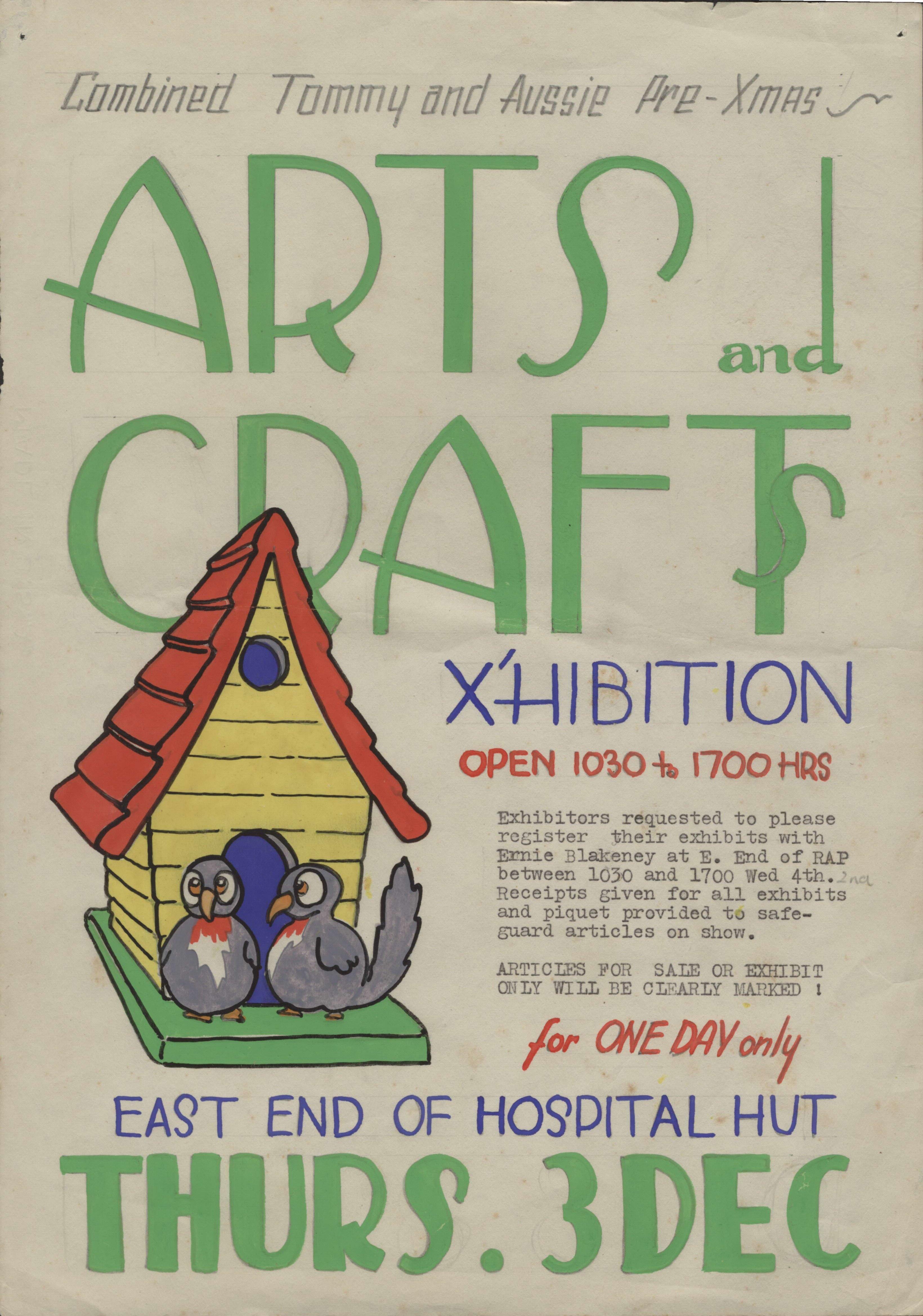

This poster neatly encapsulates the strength, resilience and meaningful purpose that the men involved in creating these posters found in their artistic endeavours. Astonishingly, designs for Christmas posters for the camp commenced as early as September 1942 and by October, de Crespigny was working on writing Cinderella as a pantomime and a ‘small gang of chaps’ were busy working on making 1500 Christmas cards from the pulp paper made in the camp.[5] The men were clearly determined to celebrate the traditional festive season as best they could, despite their circumstances. When the news of their move to Makasura was confirmed in early November 1942, de Crespigny deeply regretted the dashing of all the plans that had been made for the festive season. As he sadly noted, ‘Goodbye to all our hopes of Christmas celebrations together. Pantomime, fete, sports and Xmas dinner.’[6] Yet camp life at Makasura was little different to camp life at Bandoeng and on 5 December de Crespigny rather flippantly wrote in his diary ‘only 20 more shopping days before Xmas!’ By 24 December however, his mood had become a little more solemn and brooding; So here we are on Xmas Eve. This is the third Xmas I have spent abroad – 1st in Palestine – 2nd in Army of Occupation in Syria and now a POW in Java. I hope to God the next will be as a civilian in Australia.

By all accounts however, Christmas Day 1942 was in fact a rather memorable one.

Lt Col Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop recorded that the Christmas festivities continued long into the night;

In December 1942, thousands of Allied troops spent Christmas as prisoners of the Japanese and many made the most of their situation. Some would have longed for their loved ones back home, others might have reminisced of Christmases past and all would have wondered what 1943 was going to bring. Sadly for too many, 1942 would in fact be the last time they celebrated Christmas.

FOOTNOTES

[1] John de Crespigny, Diary entry, Saturday 29 August 1942.

[2] John de Crespigny, Diary entry, Tuesday 27 October 1942.

[3] John de Crespigny, Diary entry, Monday 2 November 1942.

[4] John de Crespigny, Diary entry, Monday 30 November 1942.

[5] John de Crespigny, Diary entry, Thursday 29 October 1942.

[6] John de Crespigny, Diary entry, Monday 2 November 1942.