When Singapore fell to the Imperial Japanese Army in February 1942 and Java surrendered in the following month, thousands of Allied servicemen serving in the South-East Asian theatre became prisoners of war. For the first few months, they were treated relatively well and were largely left to their own devices. It was only later that the primitive, brutal work camps established along the jungle route of the Burma-Thailand railway would come to characterise life as a POW and cause the death of thousands.

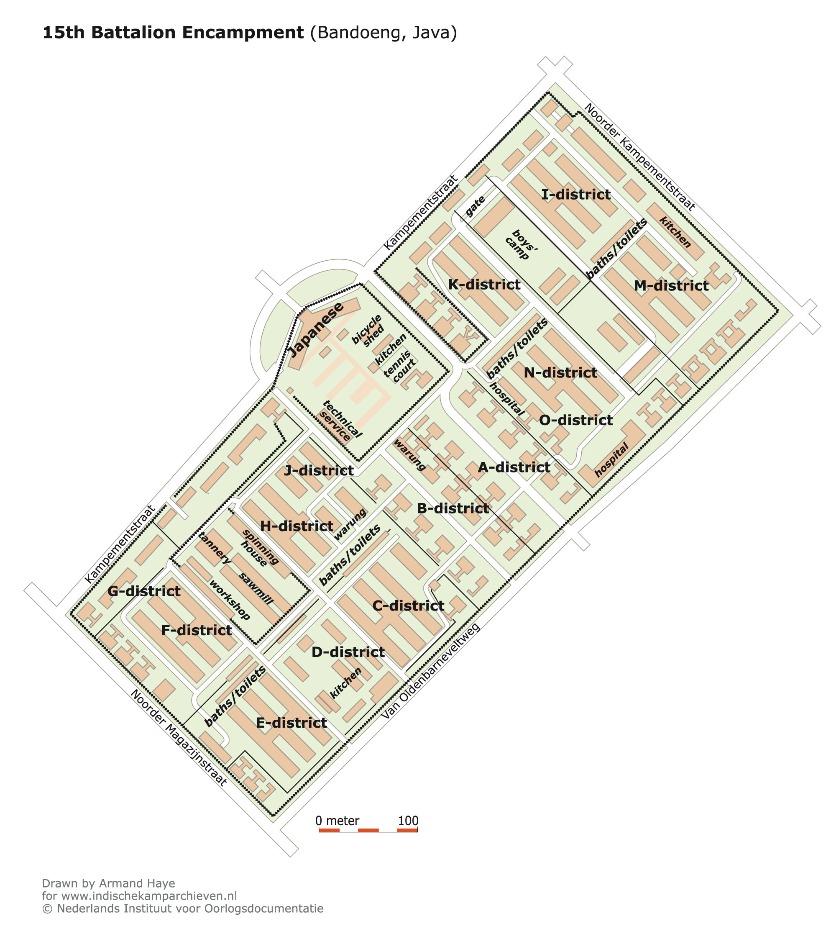

The posters in the de Crespigny exhibition were created by prisoners at the No. 12 Bandoeng Camp in West Java, and by some of the same group who were later moved to camp No. 5, Makasura in Batavia in November 1942. The camp at Bandoeng housed a multi-national mix of British, Dutch, Australian, New Zealand, and Canadian servicemen, plus Portuguese, Ambonese and Menadonese soldiers who had been serving in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army. Records show that by mid-June 1942 there were more than 3,500 men interned here in substantial brick-built facilities. Much of the camp administration fell to the Dutch officers who had local contacts in the town and the Japanese initially allowed a certain amount of interaction and commerce between the camp inmates and the townspeople. There was adequate room for the prisoners themselves, but restlessness, boredom and ennui were an ever-present threat to maintaining discipline and morale during the first few months of their captivity.

Following a series of meetings held by the senior officers in each national group, it was decided that educational and vocational lectures, sporting events, plays, musical performances and other creative activities would be introduced in the camp. There was certainly no lack of academic and artistic talent among the men, and the Bandoeng barracks provided offices, lecture rooms and a large outdoor theatre space, which was fondly referred to as ‘Radio City’. By June 1942, a ‘camp education scheme’ – also known as the ‘camp university’ had been set up, as had a large and thriving lending library and a flourishing arts and crafts school. From basic elementary instruction to the heights of university standards, the educational courses included English language and literature, arithmetic, geography, history, and ancient and modern languages. Other, more technical classes were also provided, such as publishing, architecture, and even agriculture and various skilled trades. In his diary, Lt Col Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop, the Camp Commandant recorded that by September 1942, over 1200 students had enrolled in 30 subjects, with 144 classes being taught weekly by 40 instructors.[1]

Major John de Crespigny with a small band of talented cartoonists, amateur artists and sketchers working under his creative direction, made hundreds of brightly coloured posters to advertise what activities and events were happening in the Bandoeng camp. That some of these posters survived and made it back to Australia after the war is extraordinary. We don’t know for certain how they were preserved. Perhaps they were buried and later dug up? Or maybe they were stashed away in a cupboard in one of the camps classrooms and retrieved after the war? What is more assured, is the intimate snapshot and visual record that these posters reveal about camp life and the strength, resilience and hope of the men who created them.

Read more on John Chauncy Champion de Crespigny

[1] E. E. Dunlop, The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop; Java and the Burma-Thailand Railway 1942-1945, Nelson, Victoria, 1996, Diary entry, Tuesday 3 September 1942, p 85.