Photo: View of the ruins of Messines, in Belgium. The foreground is littered with debris. AWM E01291.

At 3.10 am on 7 June 1917, nineteen giant mines were detonated under German trenches along the Messines-Wytschaete Ridge to the south of Ypres in Western Belgium. In the largest secret operation of the Great War, British and Commonwealth mining companies (including the 1st Australian Tunnelling Company) had placed more than one million pounds of ammonal beneath and behind enemy lines. In little more than twenty seconds, thousands of German soldiers disappeared.

Watching from his vantage point high on Mount Kemmel some seven kilometres away, the British war correspondent Phillip Gibbs described the scene as ‘the most diabolical splendour I have ever seen.’[2] And, as the mushroom shaped clouds flung huge clods of earth and debris back to the ground, and dust and smoke shrouded the landscape, the British Second Army, including Australian and New Zealand troops were readied to advance across no man’s land to storm the ridge.

The Battle of Messines was the first large-scale action involving the AIF in Belgium. During the battle the Australians encountered for the first time the German innovation of concrete blockhouses, which they dubbed ‘pillboxes.’[3] Messines also marked the entry of the newly formed 3rd Australian Division commanded by Major-General John Monash. The other Australians in the 4th Division under Major-General William Holmes contained a high proportion of Gallipoli veterans and had been fighting on the Western Front for over a year; they had been badly mauled at Bullecourt just six weeks earlier. This time however, the tactics for Messines had been meticulously planned and the troops on the ground were heavily supported by great volumes of artillery fire, armoured vehicles and an air force in the skies above.

Photo: Messines, Belgium, 1917. A German Army trench near Messines Ridge which had been destroyed by the advancing British Army. The bodies of two German soldiers are still in the trench. AWM H09212.

The huge explosion, followed by a well-planned and well-coordinated attack (known as the ‘all arms’ offensive model) left the German strategy of static defence vulnerable and the remaining Germans were dazed and outnumbered; many subsequently surrendered. By the end of the day, one of the strongest positions on the Western Front had fallen with relative ease. Although another ’72 hours of hell’ endured on the reverse side of the ridge, the Battle of Messines was the greatest British tactical victory in almost three years of war, a war which up to date had been one characterised by deadlock and stalemate. It came with a heavy price however; the 3rd Division alone lost 6,800 men killed or badly wounded, which was almost two thirds of its strength.

Brothers from Stanmore; 1402 Clarence Douglas Blackadder and 1403 Edwin Roland Blackadder

Photo: (Left to right) Brothers from Stanmore; 1402 Clarence Douglas Blackadder and 1403 Edwin Roland Blackadder. Anzac Memorial Collection.

Clarence and Edwin Blackadder were living with their parents on Temple Street in Stanmore when they enlisted with the AIF on 7 February 1916. Edwin was twenty-two years of age and worked as a bank clerk whilst Clarence, at twenty-four years of age, was a commercial traveller. Both were posted to the 33rd Battalion as Drivers. The 33rd had been formed in January 1916 at an AIF camp in the grounds of the Armidale showground in northern NSW. The Battalion's Commanding Officer was Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Morshead, who would famously command the 9th Australian Division during the Second World War.

The 33rd Battalion became part of the 9th Brigade of the 3rd Australian Division. It left Sydney, aboard HMAT Marathon in May 1916. Sailing via Albany, in Western Australia, and making stops at Durban, Cape Town and Dakar, the battalion arrived in the United Kingdom on 9 July 1916 where it spent the next four months training for the rigours of trench warfare. It sailed to France in late November and moved into the trenches of the Western Front just in time for the onset of the bitterly cold winter of 1916-17. Allied operations switched to the Ypres area in Belgium in mid-1917 and it was here where the 33rd endured its first major battle at Messines. The 33rd’s casualties amounted to 92 killed in action or died of wounds, and 260 wounded – the heaviest they would suffer for the entire war.[4]

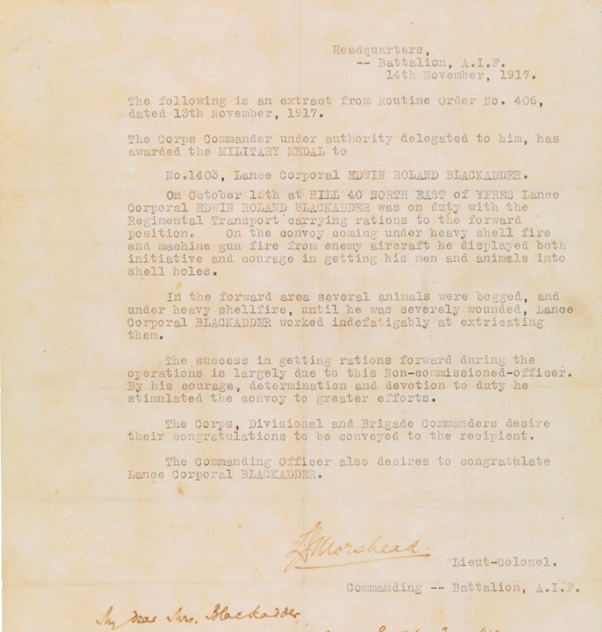

Both Clarence and Edwin Blackadder survived Messines, and on 19 June 1917 Edwin was promoted to Lance Corporal. The next major action for the 33rd would be during the Third Battle of Ypres in October 1917. Unfortunately both brothers were wounded that month. On 15 October, Edwin was on duty with the regimental transport at Hill 40, North East of Ypres, carrying rations to the forward position. On his convoy coming under heavy shell fire and machine gun fire from enemy aircraft, ‘he displayed both initiative and courage’ and managed to successfully guide his men and animals into shell holes. Some of the animals became bogged down however, and notwithstanding the relentless bombardment, Blackadder worked ‘indefatigably at extricating them’ despite suffering a severe shrapnel wound to his left thigh. For his ‘courage, determination and devotion to duty’, Edwin Blackadder was later awarded the Military Medal for his outstanding act of bravery.

On 27 October, he was invalided to England and spent the next seven months recovering at the Graylingwell War Hospital in Chichester. Despite the very great honour of the Military Medal, Edwin Blackadder’s serious leg wound meant that his war was now effectively over. On 7 June 1918, he departed Britain aboard HMAT Essex and arrived back in Sydney on 1 August 1918. He was discharged as medically unfit from the AIF on 15 February 1919.[5]

Image: 1403 LC Edwin Roland Blackadder, Military Medal Citation, Anzac Memorial Collection.

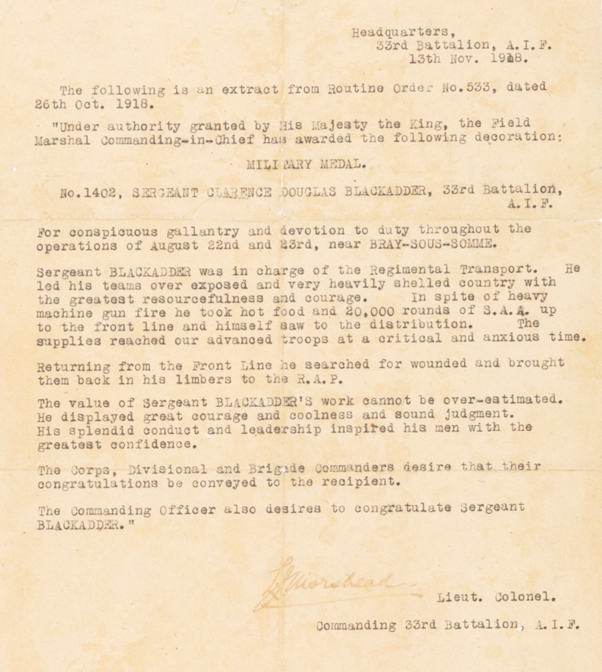

Clarence Blackadder was wounded on 26 October 1917 although, unlike Edwin’s injury, it did not incapacitate him for long. By late December he was on recreation leave in Paris where he saw in the new year, before returning to his battalion.[6] When the German Army launched its last great offensive in the spring of 1918, the 33rd was part of the force deployed to defend the approaches to Amiens around Villers-Bretonneux. It took part in a counter-attack at Hangard Wood on 30 March and it helped to defeat a major drive on Villers-Bretonneux on 4 April. Later in 1918, the 33rd fought at the battle of Amiens on 8 August, during the rapid advance that followed, and in the operation that breached the Hindenburg Line at the end of September, thus sealing Germany's eventual defeat.[7]

In November 1918 Clarence Blackadder was informed that he had been awarded the Military Medal for his ‘conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty’ throughout the operations of August 22 and 23 1918. During the successful battle for Chuignes, Blackadder had ‘led his teams over exposed and very heavily shelled country with the greatest resourcefulness and courage. In spite of heavy machine gun fire he took hot food and 20,000 rounds of S.A.A. up to the front line and himself saw to the distribution.’ On his return, he brought many injured men back with him and his ‘splendid conduct and leadership inspired his men with the greatest confidence.’

Image: 1402 Sergeant Clarence Blackadder, Military Medal Citation, Anzac Memorial Collection.

Clarence Blackadder was suffering from traumatic neuritis in the early part of 1919 and he was invalided to England. Upon his recovery, he took advantage of the AIF non-military employment scheme which kept thousands of Australians stranded overseas usefully occupied whilst awaiting a ship to carry them home. Between May and August 1919 Blackadder gained work experience with a chemical export company in London. They gave him a rather glowing report at the end of his placement ‘during which time he took every advantage of the opportunities afforded him – was attentive in his work, eager to learn and showed satisfactory progress, his conduct throughout was perfectly satisfactory.’ Clarence Blackadder finally left England in September 1919 and returned to the family home in Stanmore. He was discharged from the AIF on 2 December 1919. After the war, perhaps due to his work experience in London in 1919, he became a chemist. In 1926 he married Annie Winifred Pattenden and lived in Rose Bay until his death on 17 July 1960 aged 69 years.[8]

The Blackadder Collection at the Anzac Memorial

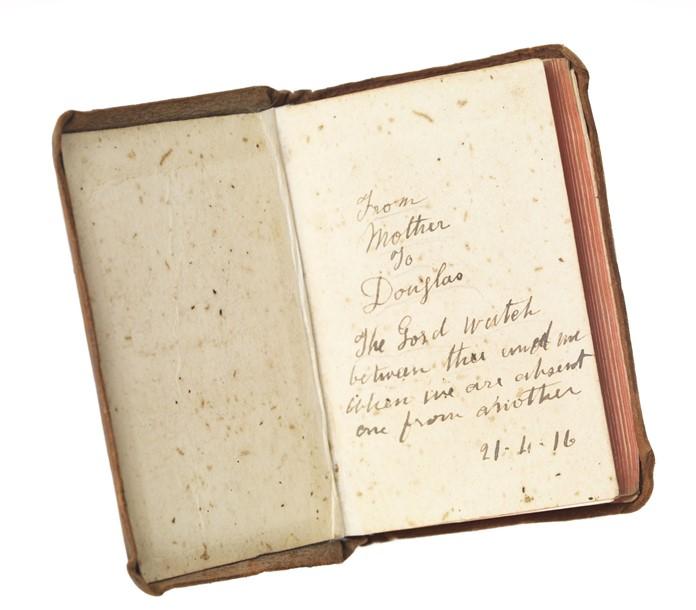

In 1997 Clarence Blackadder’s children donated a wonderful collection of their father’s wartime effects to the Anzac Memorial. The donation included his service medals and Military Medal, identity disk, a gold wrist watch, a leather-bound New Testament given to him by his mother before he embarked for the war, and a number of letters, photographs and postcards.

Lest we forget.

Notes

- Craig Deayton, The Battle of Messines 1917, Australian Army Campaigns Series 18, Army History Unit, Canberra, 2017, p 4.

- Craig Deayton, The Battle of Messines 1917, Australian Army Campaigns Series 18, Army History Unit, Canberra, 2017, p 4.

- Chris Coulthard-Clark, The Encyclopedia of Australia’s Battles, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2001 edition, p 130.

- John Edwards, Never a Backward Step: A History of First 33rd Battalion, AIF, Bettong Books, Grafton, New South Wales, 1996, p 47.

- In 1923 Blackadder was one of the founders of the British Standard Machinery Company which imported and distributed tractors and road making machines and specialised in engineering works such as bridge building. He married Mabel Florence Nihill, a stenographer from Haberfield in 1937 and they had two children. The family lived in Double Bay. He died in June 1961 aged 68 years. Sadly Mable had died in May 1959 aged just 52 years.

- He was promoted to Lance Corporal in October 1917 and in July 1918 was promoted to Sergeant.

- The 33rd Battalion were disbanded in May 1919.

- Annie Blackadder died on 11 August 1974.