Artillery had protected Sydney, the principal British settlement in New South Wales, from further incursion from the sea soon after the first landing at Sydney Cove. In 1788 the first artillery pieces – 6-pounders from HMS Sirius – were mounted at East Battery, on the site of what is now the Sydney Opera House. Later, batteries were built at West Battery, on Dawes Point (under what became the southern buttress of the Harbour Bridge) and in 1801 on Georges Head, commanding the passage through the Heads. These guns were manned by sailors from the warships of the First Fleet, and later by Marines and men of the New South Wales Corps. The guns were puny and the soldiers largely inexpert gunners; but they did not see any challenge to British rule.

Image: A View of the Cove and part of Sydney, New South Wales, taken from Dawes Point ca. 1818, watercolour drawn by convict artist Joseph Lycett, State Library of New South Wales.

In 1839, though, the arrival of two American warships of the South Seas expedition entered Sydney Harbour, unexpectedly, at night and without a pilot which increased concern about Sydney’s vulnerability. Under Governor Sir George Gipps batteries were built at Bradleys Head, South Head and on Pinchgut Island, despite the fact that the colony had few antiquated guns and no trained gunners at all.

Image: Fort Macquarie from Pinchgut, watercolour by Frederick Garling, ca. 1850, Dixson Gallery, State Library of New South Wales.

Image: Government House and Fort Macquarie from the Botanical Gardens, 1846, George Edwards Peacock, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales.

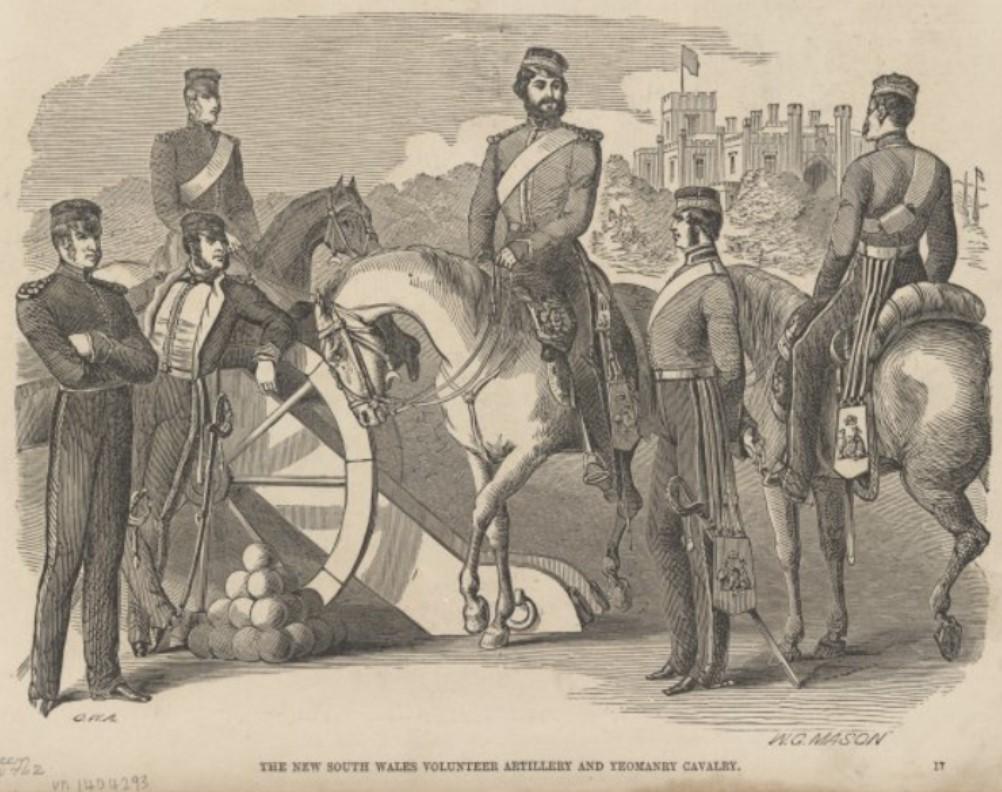

The discovery of gold in 1851 transformed New South Wales’s population, society and economy, and its awareness of the need to develop effective defences to protect the increasingly prosperous colony. The outbreak of war between Britain and Russia in 1854 brought fear of surprise attack, and stimulated both another wave of battery construction, but also the beginning of artillery units in Australia. Just before the war, the New South Wales government authorised the creation of units of volunteers, including a company of artillery, and the outbreak of war, though distant, stimulated recruitment. Enthusiastic part-time gunners trained on the old batteries in the crenellated Fort Macquarie (the successor to the East Battery) and at Fort Phillip, the grandiose name for the battery on Dawes Point. These volunteers were disbanded with the war’s end in 1856.

Image: The New South Wales Volunteer Artillery and Yeomanry Cavalry, Walter G. Mason, 1857, National Library of Australia.

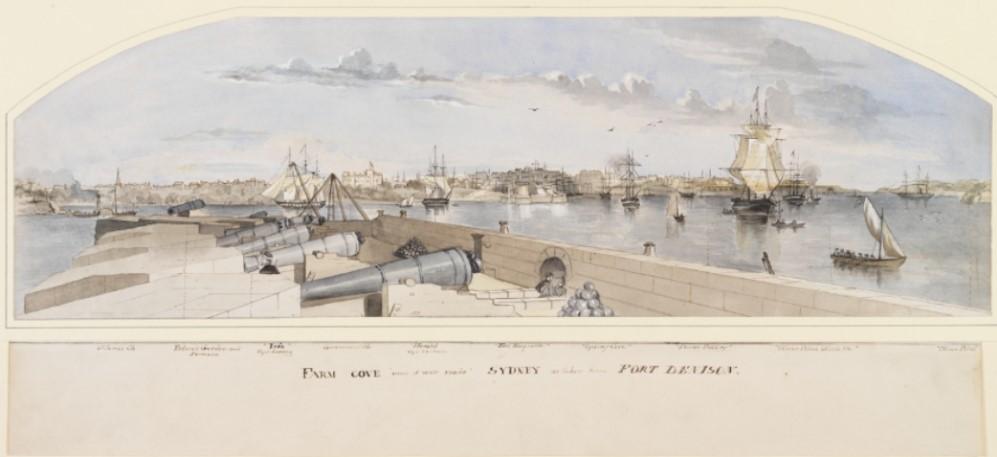

Sir William Denison who served as the Governor of New South Wales between 1855 and 1861, (and who was a Royal Engineer) sought authorisation for a further wave of defensive works around Sydney Harbour, with its centrepiece the stone-built ‘Martello’ fort constructed on Pinchgut Island. The distinctive tower was based on the design of forts that surrounded the British coastline during the Napoleonic Wars and it was the only one built in Australia. It was equipped with two 10-inch guns and 12 eight-inch pounders.

Denison also obtained the first British gunners sent to Australia. A company of the Royal Artillery (No. 3 of the 7th Battalion, later re-numbered No. 3 Battery, 12th Brigade) arrived in 1856. Until 1870 these British gunners (replaced in 1864 by No. 1 Battery, 15th Brigade) operated the guns defending Sydney. Those guns can still be seen in the preserved Fort Denison.

Image: Farm Cove “man of war roads” Sydney as taken from Fort Denison, ca. 1859-1860, James Glen Wilson, State Library of New South Wales.

As ‘volunteer mania’ spread around the British empire following a short-lived war-scare between Britain and France in 1859, British colonies also formed volunteer military units. In 1860, New South Wales revived the idea of forming a volunteer defence force and raised three artillery companies to man batteries in Sydney and Newcastle. By 1863 the New South Wales Volunteer Corps included 282 gunners. Artillery service was popular, attracting city dwellers in particular and by 1870 New South Wales had eight companies of artillery, some operating mobile field batteries, and some manning the batteries defending the coast.

Image: Government House, Fort Macquarie, Sydney ca. 1858-1859, photograph by William Hetzer, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

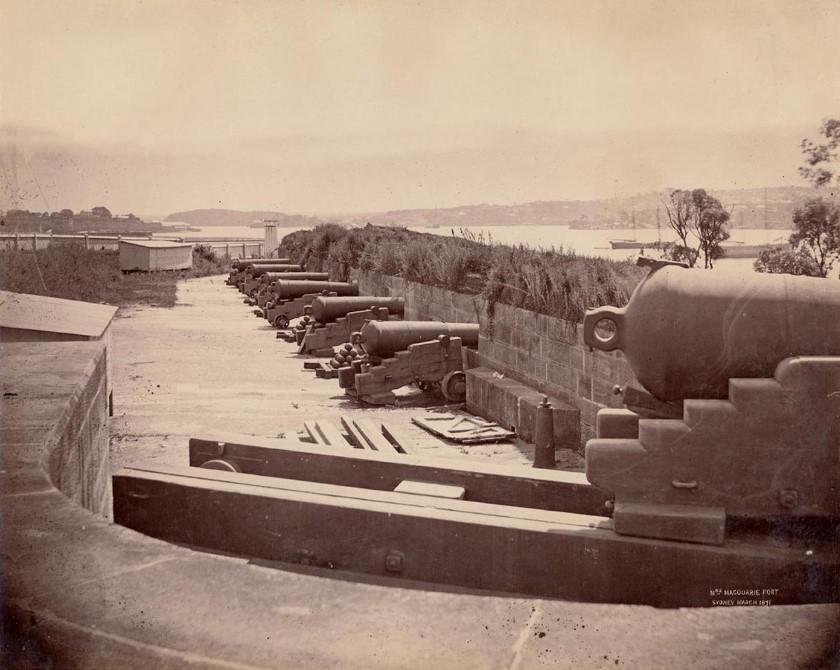

The willingness of colonial governments to take responsibility for defence encouraged the complementary movement in the British government to withdraw the imperial garrisons. In 1870 the last infantry regiment, the 18th Royal Irish and the Royal Artillery gunners, sailed from Sydney, ending the British Army’s long association in the defence of New South Wales. The British gunners were replaced by a new regular unit, the New South Wales Artillery which was authorised in 1871.

Image: Dawes Battery, Sydney Harbour, ca. 1870s, State Library of New South Wales.

Though the first permanent New South Wales unit, more than two-thirds of the artillery’s members were (as its nominal roll discloses) British migrants, and some were discharged British gunners. Its long-serving Battery Sergeant-Major, for example, was Staff Sergeant Henry Green, a former Royal Artilleryman and a veteran of the Crimean War. Green was the first man enrolled in the new unit, proudly bearing the service number ‘1’.

The new battery operated both field and ‘garrison’ – that is, fixed guns, and spent much of its first years installing 25 80-pounder rifled muzzle-loading guns in defences built at South, Middle and George Heads and also at Signal Hill, Newcastle, and Bare Island, at the mouth of Botany Bay. By 1877 New South Wales had raised three batteries of artillery, known as the Regiment of the New South Wales Artillery, numbering 13 officers and 361 men. Even its own historian, however, acknowledged that it was barely effective in manning the colony’s coastal defences because it had too diverse a task, too few men and obsolescent weapons.

Image: Mrs Macquarie’s Fort, Sydney, 1871, Charles Percy Pickering, State Library of New South Wales.

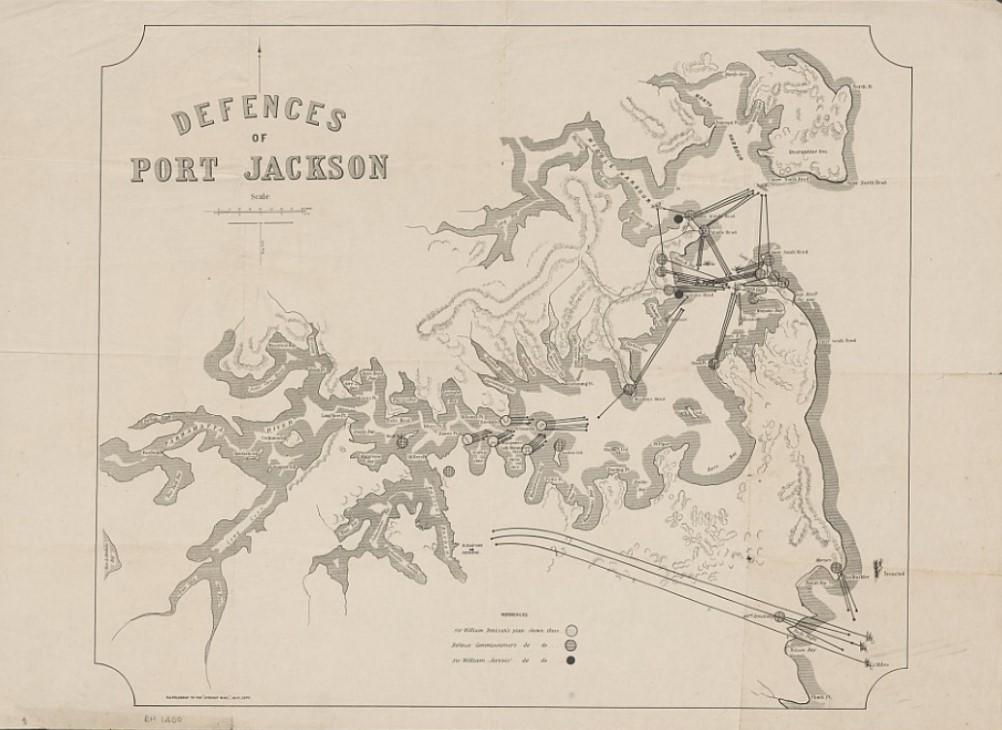

The completion in 1872 of the international telegraph connecting Australia to the world exacerbated concern at Australia’s vulnerability to attack; contemporaries imagined Russian, French or German threats (all groundless) or raids by American ‘filibusters’, latter-day pirates, who plundered South America’s coasts. In the mid-1870s Henry Parkes, the Premier of New South Wales, arranged for a Royal Engineer officer, Colonel Sir William Jervois, to advise on more effective defences. With Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Scratchley, in 1877 the pair inspected the defences of several colonies and recommended that while relying largely on the shield provided by the Royal Navy, they should build stronger coastal forts. New South Wales’s defensive works now also extended from Sydney Harbour to Signal Hill in Wollongong and a strengthened fort at Newcastle named Fort Scratchley. The newer and more powerful guns mounted in them needed trained gunners, and the reformed permanent colonial artillery units became the basis of what became the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery.

Image: Defences of Port Jackson: supplement to the Sydney Mail, July 1877, National Library of Australia.

Sharing the same responsibility, often the same guns and the traditions of the parent Royal Artillery (which often provided their senior officers), the colonial artillery forces often had more in common with each other than with the infantry, lancers or mounted rifles of their own colonial forces. In 1889 Major-General Sir Alexander Tulloch (the Commandant in Victoria) recommended to the New South Wales government that all the colonial artillery corps be unified, an idea reinforced in the same year when a British officer, Major-General Bevan Edwards, recommended that garrison artillery and other defensive units be brought together in an ‘Australian Fortress Corps’. Unification however took a further decade.

The arrival as Commandant in New South Wales in 1893 of Major-General Edward Hutton gave impetus towards what contemporaries called ‘military federation’, paralleling the movement in several colonies towards political federation. As well as reinvigorating the colony’s defence force, he advocated the creation of a federal regiment of artillery, a move continued by his successor, Major General Sir George French, under whom the New South Wales Artillery had grown to 466 men, the largest artillery force in the Australian colonies.

Image: Fort Denison, ca. 1900 by John Henry Harvey, State Library of Victoria.

In the mid-1890s the informal co-operation between colonial gunners became more organised, and colonial commandants lobbied British authorities to unite them. (The War Office decried the idea, seeing no benefit to the wider imperial army in unification.) Still, the colonial officers, influenced by both concern for military efficiency and by the prevailing mood in favour of federation, persisted, and in July 1899 Queen Victoria approved the formation of the Royal Australian Artillery, formed from units in New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland, the three colonies with the largest and most complex artillery forces. This regiment was one of Australia’s first federal institutions.

In 1901 New South Wales’s defence force formed part of the army of the new Commonwealth of Australia, its artillery units still manning the coastal defences created in the previous half-century for the protection of the coast of Australia.

Further reading

David Horner’s The Gunners: A History of Australian Artillery (1995) gives a comprehensive account of the development of artillery in colonial Australia.

Richmond Cubis’s A History of ‘A’ Battery, New South Wales Artillery 1871-1899 (1978) is a history of the regiment.

Peter Oppenheim’s The Fragile Forts: The Fixed Defences of Sydney Harbour 1788-1963 tells the story of Sydney’s forts.

Craig Wilcox’s For Hearths and Homes: Citizen Soldiering in Australia 1854-1945 (1998) places the New South Wales volunteers in context, while Peter Stanley’s The Remote Garrison: the British Army in Australia 1788-1870 (1986) deals briefly with Sydney’s Royal Artillerymen, and his essay ‘Soldiers and Fellow-Countrymen’ (in Australia: Two Centuries of War and Peace, 1988) places the defenders of Sydney in the context of Australia’s vulnerability to external threat.