Two decisive naval battles, with almost opposite outcomes, affected Australia between February and May 1942. In the first, the combined American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) fleet suffered a catastrophic defeat at the hands of the Imperial Japanese Navy, leading to the Japanese occupation of the entire Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). The second, two months later, was more chaotic and less clear-cut, as the Americans suffered heavier losses but blunted Japan’s push towards capturing Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea. It was the first setback in Japan’s lightning campaign to control the south-east Pacific.

The Battle of the Java Sea, 27 February-1 March 1942

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 and concurrently on the Philippines on 8 December 1941 (the same day, though on the other side of the International Date Line) was the start of a dramatic advance by Japanese Army and Navy forces down south east Asia and into the Pacific. Having captured the British colonies on the Malay Peninsula, the Japanese pressed into the Dutch East Indies, whose islands were rich in oil, rubber, and food, crucial military resources that Japan desperately needed.

A Combined Striking Force of American, British, Dutch and Australian warships opposed a Japanese invasion fleet sailing south through the Macassar Strait on 27 February 1942. The ABDA force consisted of two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers and nine destroyers, some of them elderly, outdated designs, under the command of Dutch Rear Admiral Karel Doorman. Australia’s contribution was the modern light cruiser HMAS Perth.

The Japanese fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Takeo Takagi, consisted of two heavy and two light cruisers, 14 destroyers and ten transports. Its warships outgunned and outranged those of the ABDA force. Over a period of seven hours in the afternoon and evening of 27 February, the ABDA fleet repeatedly tried to attack the vulnerable Japanese transports filled with soldiers. However, the Japanese cruisers and destroyers held them off with superior firepower. Doorman knew he had little chance of success, but was determined to do his utmost to challenge the Japanese. Three successive encounters, characterised by inaccurate shooting on both sides resulted in the loss of two ABDA light cruisers, including Doorman’s flagship, and all but one of the Allied destroyers. The British cruiser Exeter left the fight with heavy damage, escorted by one destroyer. The two remaining cruisers, the USS Houston and HMAS Perth, left the battle, low on fuel and ammunition. The ABDA fleet lost 2,300 killed while the Japanese suffered merely superficial damage and the loss of 36 sailors.

The next day, with only a partial refuelling, both ships, under the command of Captain Hector Waller of HMAS Perth, were ordered to oppose a large Japanese fleet in the Sunda Strait, composed of two small carriers, five cruisers, 12 destroyers and 58 troopships. During an intense night action on 28 February-1 March, the Japanese surrounded and sank both cruisers, HMAS Perth reduced to firing practice ammunition by the end of the battle. Over 1,000 Allied sailors were lost and 675 taken prisoner.

The badly damaged HMS Exeter, along with two destroyers, was intercepted as it limped for safety, and all three ships were sunk by naval and aerial attack on 1 March. Other ABDA ships were scuttled or sunk, and the waters around the Dutch East Indies left to total Japanese control. Allied land forces in the Dutch colony were forced to surrender, with few escaping captivity. Many of the prisoners-of-war were executed or died of maltreatment during captivity.

The Japanese capture of the Dutch East Indies exposed Australia’s north-west coastline to Japanese aerial attacks for the next two years, including multiple devastating air raids on Darwin and Broome.

The Battle of the Coral Sea, 4-8 May 1942

By early May 1942, the Japanese were looking to isolate Australia from American help with simultaneous thrusts along the Solomon Islands and the capture of Port Moresby on Papua New Guinea’s southern coast, supported by two large fleet carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, the light carrier Shoho, and cruisers and destroyers under the command of Vice Admirals Shigeyoshi Inoue and Takagi.

Deciphered Japanese signals allowed Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander of US forces in the central Pacific, to guess Japanese intentions, and send the fleet carriers Yorktown and Lexington, under Rear Admiral Jack Fletcher, along with cruisers and destroyers to the Coral Sea. One cruiser task force was commanded by Australian Rear Admiral John Crace, and included the cruisers HMAS Australia and Hobart, and was placed as a blocking force between Port Moresby and the Japanese landing force.

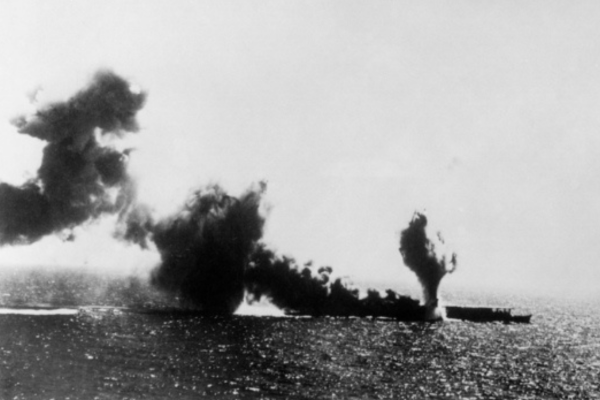

Both fleets spent several days searching for each other before aircraft from both sides spotted elements of the opposing forces on 7 May 1942. However, errors in reporting meant that both sides were still confused, the Japanese launching aerial attacks that sank an American oil tanker mistakenly identified as an aircraft carrier, and its accompanying destroyer, while the Americans stumbled on the Shoho, rather than the main Japanese force. The small carrier, unable to defend itself, soon suffered fatal damage and sank at 11:35, with heavy loss of life.

Both sides used the afternoon and evening to regroup. Land-based bombers on both sides attacked the Japanese invasion convoy and Crace’s force, but neither inflicted any damage. An evening strike by the Japanese carrier pilots, manned by their most experienced pilots, was ambushed by American fighters, suffering heavy losses. In the confusion of their return in the dark, several misidentified the US carriers as their own and attempted to land before realising their error.

On 8 May, both sides spotted the main fleets within minutes of each other, and launched all-out attacks. The Americans hit Shokaku with at least three bombs, forcing it to retire from the battle with heavy damage, but missed with all their torpedoes. In the meantime, the Japanese descended on the American carriers, sinking the Lexington with two torpedoes and two bombs which set off uncontrollable fires, while the Yorktown took a single bomb hit. Thinking that the Japanese still had several undamaged carriers, Fletcher withdrew.

The Japanese also withdrew, having suffered catastrophic casualties in aircrew, and were running low on fuel. While the Americans had experienced greater losses during the battle, the Japanese could not continue the planned invasion of Port Moresby.

The aftermath of the battle was significant. The Americans patched up the damaged Yorktown in a matter of days, and it played an important role in the devastating defeat of the Japanese carrier fleet at the pivotal Battle of Midway in June. On the other hand, the Japanese effectively lost two carriers for that crucial battle, the Shokaku still under repairs, while the Zuikaku’s air group was too decimated to participate. Meanwhile the Japanese attempted to take Port Moresby overland, but the Kokoda campaign also failed due to stubborn Australian resistance compounded by logistical problems.

The Battle of the Coral Sea was significant in another respect. It was the first naval battle in which the opposing fleets never saw each other. All of the offensive action was undertaken by aircraft, illustrating the decisive shift in naval power from big guns on battleships to air power projected from aircraft carriers.