When the surrender was officially announced celebrations erupted across the western world, especially in Great Britain and North America. (Russia and some of its former satellite states, Belarus, Serbia and Israel all celebrate the event on the following day, 9 May.) In London it is estimated that around a million people gathered in the streets to cheer in the news that the war was over, with Trafalgar Square, Piccadilly Circus, The Mall and Buckingham Palace being the main centres of attraction. In the United Sates the event coincided with President Harry Truman’s 61st birthday, although he had been in office for less than a month and he dedicated the victory to his predecessor President Franklin Roosevelt who had died of a brain haemorrhage on 12 April. Despite this feeling of loss, many American cities conducted their own celebrations, with New York’s Times Square being a particularly boisterous gathering place.

The jubilation was, however, tinged with an air of caution. UK Prime Minister Churchill reminded his people in a radio broadcast that Japan remained “unsubdued” and Truman told his fellow Americans that it “was a victory only half won”.

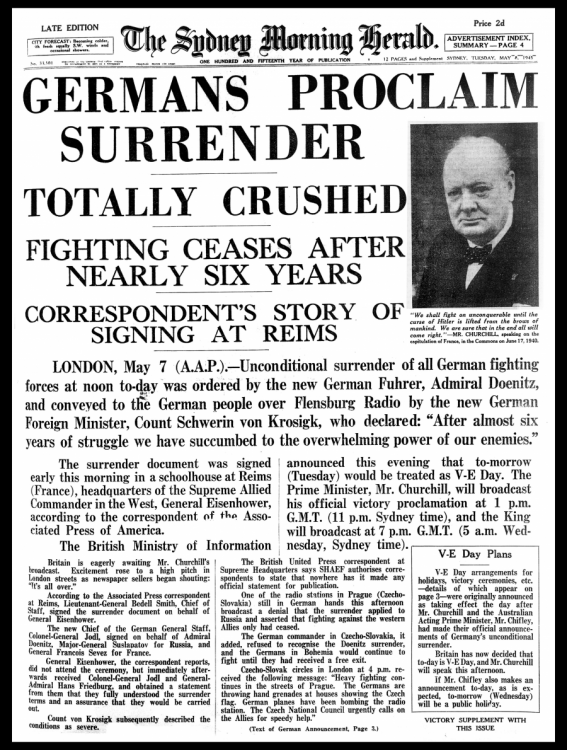

In Australia the news of the victory in Europe was greeted no less enthusiastically. The merry-making began at about 4:30 pm on the Tuesday afternoon of the 8th when the news was passed through from Europe. In Sydney, office workers began throwing shredded paper out of their windows before leaving work. This paper storm lasted more than an hour and the Sydney Morning Herald reported that the first confetti spiralled down from the Tax Office, leading one man to remark to a reporter that he hoped it was his personal tax file that had been sacrificed for the nation’s greater joy. Crowds then gathered in many public spaces such as Martin Place and by 11:00 pm in Kings Cross there were an estimated 15,000 people singing, chanting, dancing, kissing and banging pots and pans in the streets. Extra police were called in to help, which they did with good humour, as the exuberant crowds brought both vehicle and tram traffic in the city to a standstill. These noisy excesses carried on until well after midnight and someone in high authority declared the next day to be a makeshift national public holiday. So on the Wednesday morning, despite the lack of public transport, large crowds made their way to open air thanksgiving services conducted in the nation’s capitals, with 13,000 attending the one in Sydney’s Domain.

But in Australia as well, there was a quite tangible air of subdued reflection because the much closer war against the Japanese was still not over. Large numbers of servicemen were still on duty in the South-West Pacific and the East Indies and thousands of prisoners of war had yet to be released and repatriated. It would be several more months before a string of military defeats and two atomic bombs brought the Japanese to the negotiating table and the signing of the inevitable surrender documents in August 1945.