At dawn on 6 September 1943, dazed German civilians emerged from air raid shelters in cities and towns from the Dutch frontier to the Ruhr Valley to discover their homes flattened or smouldering and the countryside littered with the wrecks of British heavy bombers bought down by anti-aircraft fire or Luftwaffe night fighters.

On the route to Mannheim in the Ruhr Valley was the wreck of a four-engined Halifax. Inside the wreck were the corpses of its crew. Like so many of the crews in RAF Bomber Command, sent to destroy Germany’s military industrial ability to wage war by bombing its factories, fuel supplies and lines of communication, they were young and brave and gathered from around the British Empire.

The pilot, and therefore captain of the aircraft, was 21-year-old Pilot Officer Frank Mathers CGM from Pagewood in Sydney. Sergeant Roy Gough from Cornwall was his flight engineer. The navigator, 22-year-old Flying Officer William Simpson from Fife, was the only other officer on board. The bomb aimer was Flight Sergeant William Goldsborough, a 21-year-old from Durham. The wireless operator, Sergeant Edward French, a Londoner, had already earned the Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM), as had Scotsman Bill Speedie the 20-year-old tail gunner. In the mid-upper turret was the baby of the crew, 18-year-old Sergeant Guy Muffett from Kent.

They were a happy and popular team within 77 Squadron, RAF, who had gained media attention on their ninth operation. On 22 June they had been tasked to bomb Mulheim. Hundreds of bombers, Lancasters and Halifaxes, from airfields across Britain formed a massive stream of airborne destruction on its way to Germany that night.

Then Flight Sergeant Frank Mathers and his crew ran into flak as they crossed the enemy coast. They pressed on and just before 2am they attacked the target, releasing their bombs from 17,500 feet. The Halifax was hit by anti-aircraft fire as they completed their bomb run. The starboard outer engine burst onto flames. Seconds later they were hit again, setting the port inner engine on fire. Mathers and Gough extinguished the fires and feathered the engines but soon realised that the bomber was badly hit. Three fuel tanks were punctured. Two emptied immediately and the third was leaking fuel over the wing. The starboard aileron was useless and the fuselage was peppered and torn by shrapnel. As they turned for home, leaving flak and searchlights behind, Mathers, wrestling with the controls, ordered his men to jettison everything possible to save weight as the aircraft was losing height.

By the time they reached the Channel coast the Halifax had dropped to 3,000 feet. A friendly airfield was still a long way off. Over the sea at 2,000 feet a German night fighter, a powerful Messerschmitt 110 (Me-110), suddenly roared past out of the darkness. The German pilot and observer realised at a glance that the bomber was crippled. They swung in and attacked from the stern. Cannon shells tore through the fuselage of the Halifax miraculously missing each of the crew. Losing more height, flying on two engines and with damaged controls Mathers knew tail gunner Bill Speedie was their only hope. In his turret the Scotsman reached the same conclusion. As the Messerschmitt circled for another attack Speedie cleared the blocked ammunition feed to his guns and took careful aim. The fighter loomed large in his sights, looking much closer than the few hundred metres it was closing from, as he squeezed his triggers. The burst of fire struck the cockpit and fuselage of the Me-110 and it plummeted to the sea trailing smoke.

Weaving to avoid the fighter, the bomber had descended to 500 feet.

With dawn lightening the sky in the east Mathers nursed the crippled bomber across the English coast at barely 400 feet. His men realised they were too low to bail out. Ted French, who had stuck to his wireless for the whole trip, found a landing strip within reach. As Mathers prepared to land he discovered that the flak had smashed his landing gear. Knowing his aircraft could not stay airborne much longer, he ordered his men to crash positions and bought the aircraft in on its belly.

The teamwork, courage and survival of Mathers and his crew were an inspiration to blacked-out and ration-starved Britain. Frank Mathers and Bill Speedie were interviewed on BBC radio and featured in the force’s newspaper. Mathers was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal (CGM) and Bill Speedie and Ted French the DFM.

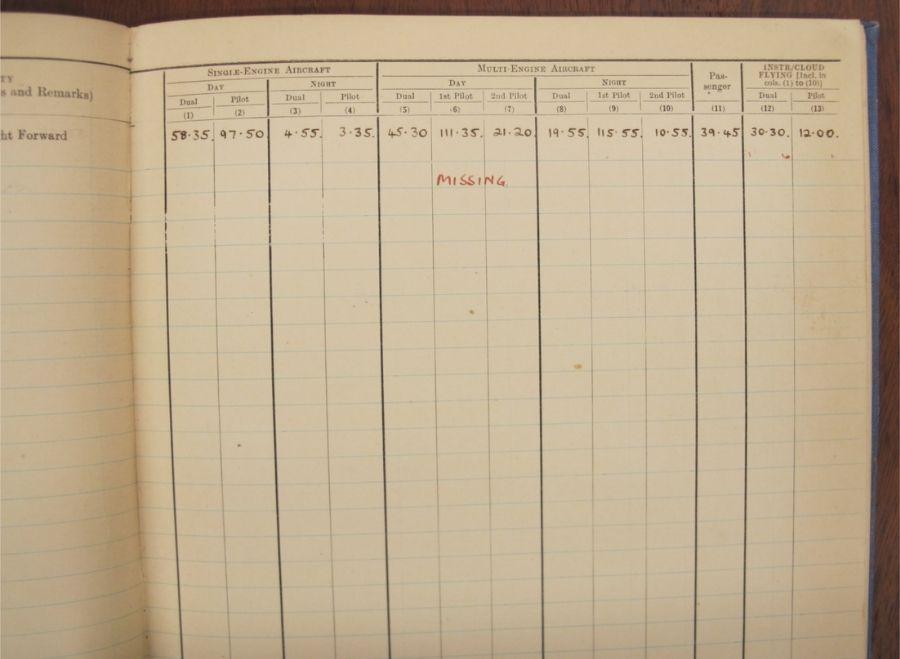

All too soon Mathers and his gallant band were back on operations. Mathers was commissioned Pilot Officer. Their tour ended in tragedy on the night of 5/6 September 1943.

Today Frank Mathers and his crew lie in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery outside the town of Durnbach in southern Germany.

His parents Francis (senior) and Eunice Jane Mathers chose the inscription on his headstone: “Only past all sorrow” While we remember you, you have not died.

On 13 April 1946 Francis Mathers accepted his son’s medal from the Governor-General at a ceremony at Government House, Sydney.

Today, Pilot Officer Frank Mathers’s medals, logbook, photographs and the letters he wrote to his mother are preserved at the Anzac Memorial in Hyde Park.

Lest we forget.

Article by Brad Manera