It was 4 November 1918 and Bo King and his fellow aviators were returning from a successful bombing mission to hit a German aerodrome at Ath in Belgium. The operation involved two Australian squadrons. King led the Snipe fighters from No. 4 Squadron, which escorted the bomb-laden SE5a fighters from No. 2 Squadron, AFC.

Flying machines in the Great War began as a novelty, an occasionally useful tool for artillery observation. By 1918 however, the potential for aircraft as a powerful tactical and strategic weapon had been firmly established. The AFC provided vital aerial support to the troops on the ground in the Middle East, the Mediterranean and over the Western Front. In very flimsy timber, wire and fabric structures they provided reconnaissance, bombing, artillery observation, and offensive patrolling. And on the ground were the fitters, riggers, repairers, mechanics and engineers who kept the new-fangled machines flying.[1]

As for the dogfight on 4 November 1918, Bolle brought down two Australian aircraft and his fellow ace, Lieutenant Ernst Bormann, another; his 16th kill. It was the day before his 21st birthday.

The Australian aviators they killed that day were among No. 4 Squadron’s most experienced pilots. Twenty-five-year-old Lieutenant Parker Symons from Adelaide was one of five brothers to serve in the Great War, only three of whom would survive . Lieutenant Arthur Pallister, a 28-year-old from Tasmania, was a 1914 volunteer who was due to return home on Anzac leave the very next day. Also killed was their flight commander, 21-year-old Captain Thomas Baker, who had already earned two Military Medals as a gunner in the artillery and tragically didn’t know it, but Bo King had recommended him for the Distinguished Flying Cross. Baker’s DFC would be awarded posthumously and it was received by his parents after the war. With just a week to go before the Armistice on 11 November 1918, Baker, Palliser and Symons were probably the last three Australians killed in action during the Great War.[2]

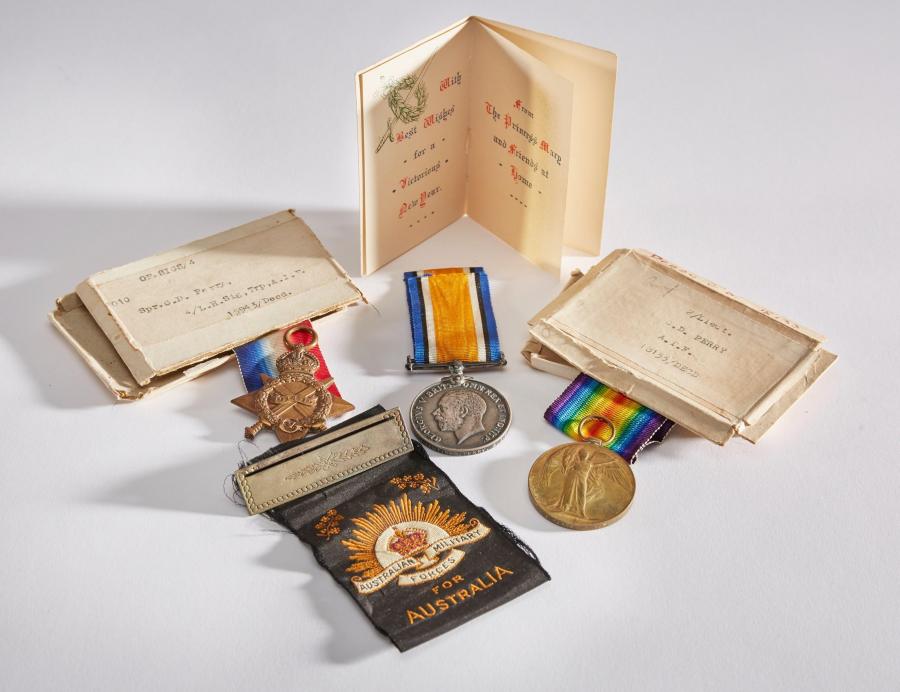

Their deaths were certainly wretched, however the AFC lost almost as many aviators in training accidents in Britain before they even made it to the Western Front.[3] One of these was Lieutenant Gilbert Perry. A small and very precious collection of memories of Perry’s life and death were recently donated to the Anzac Memorial. It includes his war service medal trio consisting of the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal and Victory Medal with original and replacement ribbons, two original medal boxes and a Mothers and Widows ribbon which was sent to his mother after his untimely death in England in June 1918.

GILBERT DOUGLAS PERRY

Gilbert Douglas Perry, from Marrickville, NSW, was working as a civil engineer and surveyor when he enlisted in the AIF on 9 March 1915, five months before his 21st birthday. Perry’s civilian occupation made him an obvious choice for the Australian Engineers and he was posted to the 13th Field Company as a sapper. The Gallipoli campaign took its toll on Perry’s health and he spent much of 1915 in and out of hospital with various maladies including tonsillitis, influenza, rheumatism and diphtheria; he did not go back to the front until January 1916. That year, his unit was heavily engaged in the Somme campaign on the Western Front and, in the summer of 1917, they were sent to the Ypres Salient in Belgium.

Standing at 5ft 4¾ inches and weighing just 146 pounds, Perry was perhaps not robust enough for the rigours of the frontline. His impaired constitution suffered through his service in the trenches and, during the battle of Passchendaele, Perry volunteered for the flying corps. In October 1917, he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and was posted as a cadet to the School of Military Aeronautics in Reading, in south-east England. By June 1918, Perry had been commissioned second lieutenant and had qualified as a pilot. He was attached to No. 5 Squadron, RFC, which was based in the historic wool town of Tetbury in Gloucester.

A TRANSFER TO THE AFC

Perry’s wartime service trajectory demonstrates how the war provided new opportunities for some AIF soldiers to re-train as pilots. The AFC offered a select few men the chance to become Australia’s first combat aviators and to experience a remarkably different war from their comrades fighting in the trenches. In early 1917, the AFC began training pilots, observers and mechanics in the United Kingdom. Aircrew were selected from volunteers from other arms such as the infantry, light horse, engineers or artillery, many of whom had previously served at the front who willingly reverted to the rank of cadet to undertake a six-week foundation course at the two Schools of Military Aeronautics in Reading and Oxford. After this, those who passed graduated to flight training at one of the four AFC training squadrons Nos. 5, 6, 7 and 8, which were based at Minchinhampton and Leighterton in Gloucestershire. Flight training in the UK consisted of dual instruction followed by up to a further twenty hours of solo flying (although some pilots, including the AFC's highest-scoring ace, ‘the Wizard of the Air’ Captain Arthur ‘Harry’ Cobby, received less) after which a pilot had to prove his ability to undertake aerial bombing, photography, formation flying, signalling, dog-fighting and artillery observation. Elementary training was undertaken on aircraft types such as Maurice Farman Shorthorns, Avro 504s and Sopwith Pups, followed by operational training on Sopwith Camels and Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.8s . Upon completion, pilots received their commission and their ‘wings’, and were allocated to the different squadrons based on their aptitude during training: the best were usually sent to scout squadrons, while the others were sent to two-seaters.[4]

AN ACCIDENTAL DEATH AND AN INQUIRY

At 11.15am on 21 June 1918, Gilbert Perry was injured in a flying accident after he had been sent up in single-control Sopwith Camel C103 to practise diving ‘preparatory to firing on the Aerodrome target’. Perry had completed 23 hours of dual training and 24 hours of solo training. In addition, he had completed just 3 hours and 15 minutes flying a Camel solo before the fatal crash. He died of his injuries (and also pneumonia) at the Tetbury Cottage Hospital just over a week later on 29 June 1918 at the age of 23 years. As was usual, a military Court of Inquiry was held into the accident in the beautiful, ancient Cotswolds town of Minchinhampton. After hearing a number of eye witness accounts, the court found that there had been ‘bad piloting’ and Perry had pulled the aircraft out of a steep dive too roughly, causing undue strain. In essence, the inquiry concluded that Perry was to blame for the accident and the complete write off of the plane.

Despite this gloomy verdict, on 2 July 1918 Perry was given a military funeral and his ‘good polished elm’ coffin was draped with the Australian flag and ‘several beautiful wreaths’. In attendance were numerous AFC officers and representatives of the AIF. He was buried in St. Saviour’s churchyard in Tetbury. His London-based uncle George Raves was also present. The details of his funeral were later sent back to his grieving family in Marrickville in an official AIF burial report. They would have been deeply comforted to know that his grave was to be turfed and an oak cross was to be erected by the AIF. Later, a much more substantial headstone was commissioned for the grave.

Perry’s many personal belongings were eventually sent back to his parents Gilbert Henry and Mary Ann Eliza Perry in Marrickville. Later, Gilbert signed for his son’s Memorial Scroll on 9 July 1921, his Memorial Plaque on 29 December 1922 and his Victory Medal on 21 January 1923. On what date Mary Ann received her Mothers and Widows ribbon remains unknown. In January 1925, the Perry’s were again mourning; this time the loss of their eldest son John Raves Stuart Perry. John, who was married with a daughter, enlisted on 25 January 1915 and served as a sergeant until his promotion to second lieutenant with the 3rd Reinforcements, 13th Battalion. In 1918 in France, he received a gun-shot wound to his arm and was transferred to a London hospital; he was later repatriated back to Australia. It seems he never fully recovered however, and as a result of his war service he died at the Lady Davidson Rehabilitation Hospital in Turramurra, NSW at the age of thirty-five.[5]

PERRY'S MEDALS

Gilbert Perry’s medals are an extraordinary addition to the Anzac Memorial collection because medals that were awarded to members of the AFC are incredibly rare. His story is also a poignant snapshot into a life lost inadvertently whilst overseas on active service. All too often, accidental deaths in war have been dismissed in official histories as ‘collateral damage’. Yet they reveal much about unintentional loss, the measures that were taken by the authorities to prevent such occurrences happening again, and the dignity granted to some men who died in accidents during the Great War.

THE LEGACY OF THE AUSTRALIAN FLYING CORPS

After the war, Australian aviators and war surplus equipment were used to establish a permanent air service and a nascent commercial aviation industry. When the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) was established in March 1921 it was staffed entirely by officers and men who had served in the Great War. In 1925, the RAAF was expanded to include a citizen force component, which was likewise dominated by AFC personalities. And AFC veterans, by now considered too old to fly, would nevertheless make considerable contributions to leadership and training in the RAAF during the Second World War.

Lest we forget.

Article by Brad Manera and Dr Catie Gilchrist

FOOTNOTES:

*Roy ‘Bo’ King, cited in Michael Molkentin, Fire in the Sky; The Australian Flying Corps in the First World War, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2010, 2012 ed, pp 45-6.

[1] In August 1914, Australia’s first military flying school opened at Point Cook in Victoria with just two instructors and four pupils. Despite its tentative beginnings, by the end of 1915, 24 more pilots had graduated and the British invited them to form a complete Australian squadron. It was officially known as No. 67 (Australian) Squadron Royal Flying Corps however it was referred to as No. 1 Squadron Australian Flying Corps (AFC). Eventually the AFC fielded four squadrons overseas and, in 1917, the AIF established four more training squadrons in Britain which supplied the AFC with airmen for the rest of the war. Over 3,700 men served in the AFC and another six hundred Australians joined British aviation arms – the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service which in April 1918 amalgamated to form the Royal Air Force. For the most comprehensive study of the AFC see Michael Molkentin, Fire in the Sky; The Australian Flying Corps in the First World War, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2010.

[2] Michael Molkentin, Fire in the Sky; The Australian Flying Corps in the First World War, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2010, 2012 ed, p 323.

[3] A total of 179 airmen (about a third of all active service pilots) were killed, wounded or taken prisoner during the war and Australian squadrons lost 60 aircraft over enemy lines. Michael Molkentin, Fire in the Sky; The Australian Flying Corps in the First World War, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2010, 2012 ed, p 337.

[4] All Australian squadrons operated within the structure of Britain’s much larger air service, the Royal Flying Corps, but retained their national identity and remained under Australian administration.

[5] There were also two daughters born to Gilbert and Mary Ann Perry – Dorothy Garland Perry (b. 1892) and Marjorie Donald Perry (b. 1900). According to the electoral roll of 1935 both daughters were living with their parents in Crows Nest and both were recorded as being employed as teachers. In 1936 Marjorie married Solomon David Phillips in Marrickville and in July 1967 she applied to Melbourne HQ for both John and Gilbert’s Gallipoli Medallions (in John’s case, she applied on behalf of his daughter.)

**Michael Molkentin, Fire in the Sky; The Australian Flying Corps in the First World War, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2010, 2012 ed, p ix.