For two-and-a-half years from October 1899, the British empire and two independent Boer republics fought a bitter and costly war over the question of the control of southern Africa and especially its mineral wealth. That war, known as the South African War or the Second Anglo-Boer War ended 120 years ago this month, when the Treaty of Vereeniging was signed in Pretoria. What is its significance?

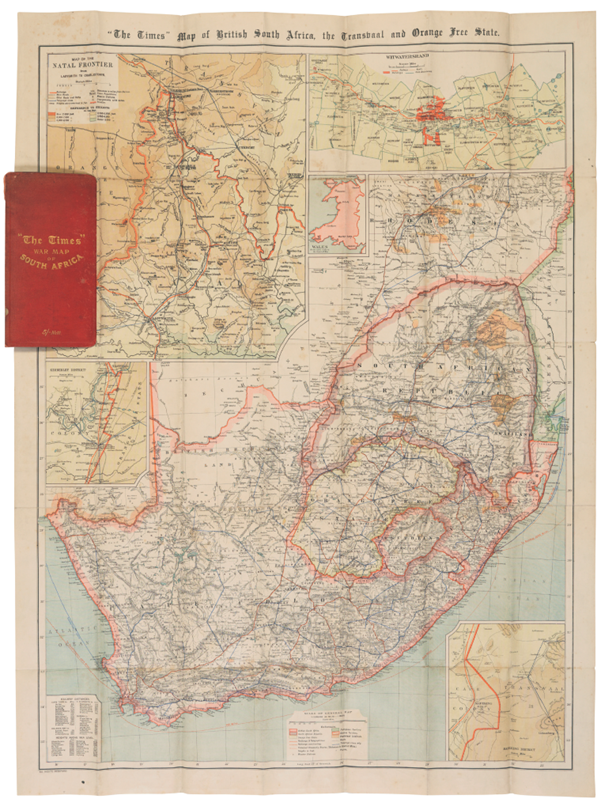

Image: The Times War Map of South Africa was printed for the benefit of the British public during the conflict 1899-1902.

By the late nineteenth century, Europeans had settled the southern quarter of the African continent, decisively defeating its original inhabitants. What is now South Africa was divided between two British colonies, Cape Colony and Natal, and two independent republics, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal, which had been founded by Dutch-Afrikaner colonists (known as ‘Boers’ or farmers) who had sought refuge from British rule by establishing independent states in the interior. With the discovery of gold and diamonds the contest between these two European settler societies sharpened, and tensions grew between them – the Boers and the British had already fought one war in 1880-81 when the Boers rebelled against and defeated British annexation.

Two decades later, as Britain clearly prepared for another war, Boer fear of again being taken over led them to pre-emptively invade British South Africa. Boers, operating as armed civilians in loose ‘commandos’ attacked British garrisons along the border and, although Britain immediately despatched large numbers of troops, the Boers humiliated British generals in a series of battles in what was known as ‘Black Week’. Britain despatched even more troops, and welcomed the help offered by the ‘white’ colonies of its empire, including Canada, New Zealand and Australia.

Australians join the war

Photo: Troop parade in Sydney prior to departing for South Africa. Francis Killeen Collection, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, PXB592.

The Australian colonies, and later the newly federated Commonwealth of Australia, immediately and enthusiastically joined the war effort of the British empire. Contingents of volunteers from all Australian colonies served in South Africa, many named ‘Bushmen’ or ‘Mounted Rifles’. They fought in several small actions, notably at the Elands River Post in August 1900 (when troops from all Australasian colonies besides South Australia withstood a Boer siege), and in the guerrilla war which began after British armies advanced into and occupied the Boer republics.

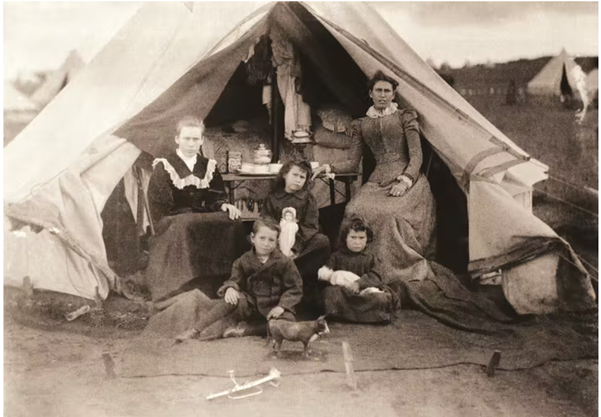

While the sheer number of British empire troops forced Boer commandos to become fugitives, their knowledge of their country prevented them from being overwhelmed. Later, under a new commander-in-chief, Lord Kitchener, the British adopted the strategy of depriving the commandos of support by interning Boer civilians in ‘concentration camps’. Tens of thousands of civilians, mainly women, children and the elderly (both European and some Africans) were held in huge, insanitary camps, where malnutrition and sickness killed over 45,000 civilians, a scandal exposed in the course of the war which harmed British prestige internationally.

Photo: Inside one of the British concentration camps. Photographical Collection, Anglo-Boer War Museum, Bloemfontein, South Africa.

The war shocked both protagonists. The world was surprised when the British empire, its largest and most powerful, found defeating the Boers so hard. Britons endured the humiliation of a series of defeats, a long and gruelling guerrilla war and the embarrassment of the exposure of their concentration camps. The Boer republics were devastated, suffering immense losses economically but also socially. While 6000 Boer combatants died, five times as many Boer civilians died in the camps, leaving a lasting legacy of bitterness.

Over 16,000 volunteers from the Australian colonies fought in the war, including, from 1901, men of the Australian Commonwealth Horse, most serving for terms of up to a year before returning home. Over 6000 men from New South Wales served in the war in six NSW contingents (of lancers, mounted rifles and bushmen, but including some gunners, a medical party and fourteen nurses). Men from NSW also served in Australian units formed in South Africa, and in British and South African units, and in the Australian Commonwealth Horse.[1] At least 200 men from NSW died serving in NSW units, though many more served in other units. Most Australians participated in the exhausting guerrilla war, chasing Boer commandos around South Africa’s veldt, seeing few significant actions but much hardship.

Photo: Mounted troopers of the 1st Battalion, Australian Commonwealth Horse, watering their horses while on the march in Transvaal, 1902. AWM A04407.

By early 1902, the Boer republics were occupied and their people were interned. Exhausted Boer commandos were still in the field as ‘bitter-enders’ but they were unable to achieve victory. Boer leaders debated how they could end their suffering and retrieve a peace they could live with.

Negotiating a peace

In April, remaining Boer political and military leaders began to debate how they could bring the war to an end. Accepting defeat, they still hoped to retain a measure of political and cultural autonomy and opened negotiations with their British counterparts. While some British figures wanted unconditional surrender and the elimination of the Boers’ Afrikaner language, the Boers’ negotiators largely gained what they sought. Britain was also tired of the largest conflict it had seen since the defeat of Napoleon and wished to see the war end.

The two sides’ representatives met in the small Transvaal town of Vereeniging (pronounced in Afrikaans ‘fer-reen-igh-een’), although the treaty was signed in Pretoria, the capital of the Transvaal, on 31 May 1902. The treaty’s main points were that all Boer combatants would surrender, be temporarily disarmed and swear allegiance to the British crown. The war ended the Boers’ independence and the two republics became part of the British empire. However, all Boers received an amnesty – their combatants returned home to their (often devastated) farms, although they were eligible for small reconstruction grants. They continued to use Afrikaans in schools, churches and courts, and while at first administered by British officials, were expected to regain self-government in a British South Africa, which was achieved within five years. While some British politicians had decried the Boers’ discrimination against the republics’ more numerous African population, the Boer delegates secured an undertaking not to discuss Black voting rights until the republics had regained self-government.

Afrikaner South Africans remained understandably embittered after the war, particularly because of the trauma of the concentration camps, but they acted to rebuild their society, economy and political power, and in time largely succeeded in imposing their notion of racial control in the Union of South Africa formed in 1910, in 1948 imposing the policy of ‘Apartheid’ which prevailed until a unified non-racial South Africa emerged, after profound struggle, in the early 1990s.

The Treaty of Vereeniging ended the Second Anglo-Boer War and laid the basis for South Africa’s Afrikaners to continue to participate in, and eventually to dominate, South Africa for much of the twentieth century. It also allowed the last Australian troops to return home, though an unknown number of Australian veterans remained in South Africa as settlers.