On 24 July 1900, during a skirmish at Stinkhoutboom, near Vredefort, Captain Neville Howse of the NSW Army Medical Corps witnessed a bugler being shot[1]. Howse, a practicing surgeon from Orange, NSW, “went out under heavy crossfire” to retrieve the incapacitated soldier. During the daring rescue, his horse was shot and killed beneath him. Undeterred, Howse proceeded on foot, “picked up [the] wounded man and carried him to a place of shelter”[2].

For this extraordinary act of valour, Howse became the first Australian awarded the Victoria Cross; Britain’s highest military award. At once, the gallant doctor achieved celebrity as Australia’s own ‘VC hero’[3]. To date, Howse remains the only member of Australia’s medical services to receive the Victoria Cross.

FROM SYDNEY TO STERKSTROOM

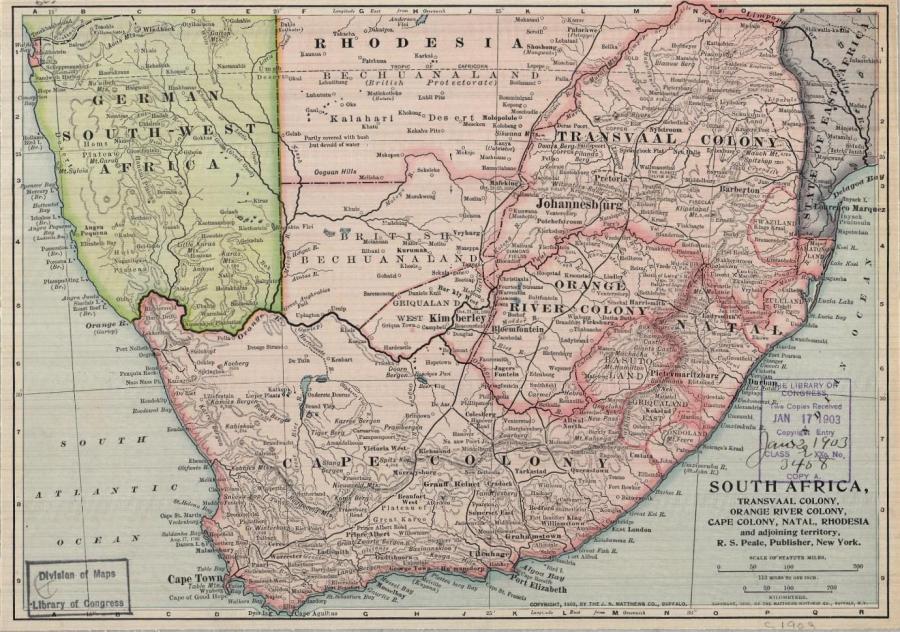

Private Patrick Murray sailed for South Africa as part of the Second Contingent of the New South Wales Army Medical Corps on 17 January 1900. Upon its arrival at Cape Town on 17 February 1900, Murray’s vessel Morovian was redirected to East London (Cape Colony), and thence to Sterkstroom. Here, under the command of Major William Eames, a fellow Novocastrian, Murray was taken on strength of the No. 2 Bearer Company. The Official Records qualify the assets inherent of the men selected for the role: “…only strong lusty men were accepted, or trained stretcher bearers”[4].

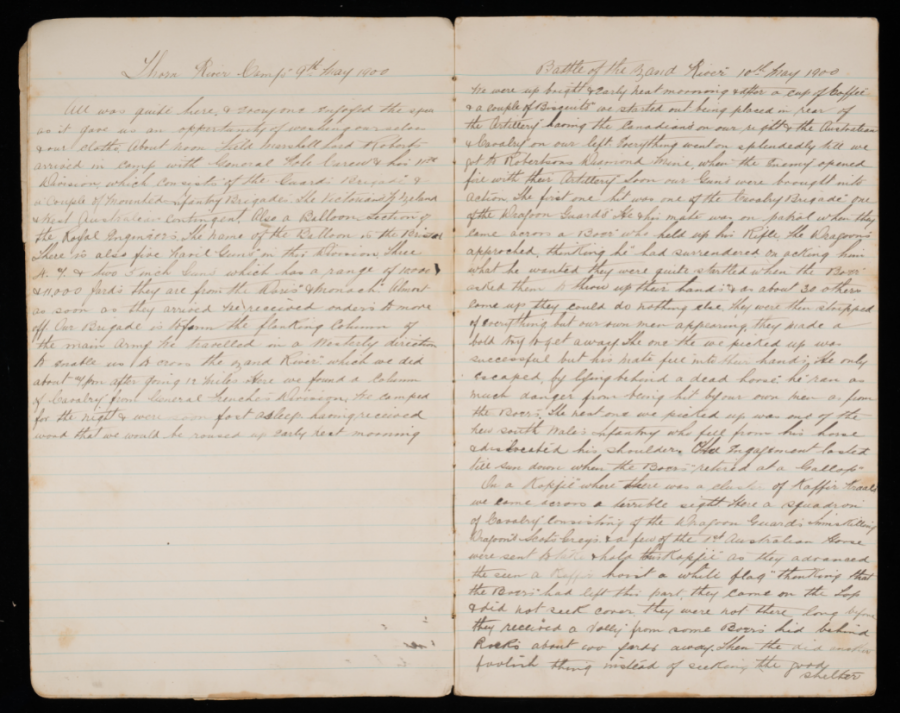

Once organised, the bearer companies of the Second Contingent commenced operations in support of the British counter-offensive through the Orange Free State. It is at Dewetsdorp on 19 April 1900 that Murray’s diary begins.

INTO THE FRAY

Murray’s account of the action at Dewetsdorp from 19-24 April 1900 offers a horrifying glimpse at the nature of the fighting.

“[…] we could see shells dropping about a quarter of a mile in front of our camp, but they did not do any harm. The Boers had evidently brought a gun into a more advantageous position and had got the range a little short, but they managed to drop a shell into the transport which took off a native driver’s leg at the knee. It was a horrible sight; the bone being stripped off the flesh for about 12 inches. The shells commenced to drop thickly close to our operating tent, the Boers evidently not caring whether a hospital was there or not. All the time this was going on our 15 pounder were making good practice and bursting beautifully over the Boer trenches.”

With a particularly dry sense of humour, Murray goes on to describe the vastly different human reactions produced by the men with whom he served.

“[…] it was very funny to see the manner in which some of our fellows ran here and there to avoid the coming shells, some of them went so far as to plant themselves behind the horse fodder so as to be out of harm’s way and others said that they could see the shells coming, but when they were laughed at got quite offended at being doubted, allowance had to be made for them as they innocently did believe that the shells could be seen.”

On 24 April 1900, Murray’s column was detached from Rundle’s Division, “after doing splendid work, and ordered to Bloemfontein, with 76 sick and wounded at which place we arrived on the 25th April.”

By May 1900, the northward advance to Pretoria was well underway. Murray’s description of his part in the Battle of Zand River on 10 May is certainly a bleak one. Once more, the callous nature of the fighting is brought to the fore, though, in this instance, Murray offers no relief of humour.

“The Engagement lasted till sun down when the Boers retired at a gallop. On a kopje* (*rocky hill)[…]we came across a terrible sight. Here a squadron of Calvary (*including the 1st Australian Horse) […] were sent to take and hold this kopje. As they advanced they seen [sic] a Kaffir* (*historic European settler slang meaning an indigenous African, now considered a racial slur) hoist a white flag. Thinking that the Boers had left this part, they came on the top and did not seek cover. They were not there long before they received a volly [sic] from some Boers hid behind rocks about 100 yards away. Then they did another foolish thing. Instead of seeking the good shelter the Kopje afforded, they ran for their horses. This is when they lost. The horses were shot in heaps and out of 90 men only two escaped. […] We removed the wounded to the Kaffir Kraals* (*an African village) and buried the dead and we had a terrible time looking after the poor fellows who we removed next day to Ventersburg Road Railway Station where we formed a temporary hospital.”

WITH SKILL AND GALLANTRY

Such was the renown of the New South Wales Army Medical Corps and, later, the Australian Army Medical Corps, both during and after the South African War. “It was thus also that they acquitted themselves with skill and gallantry that elicited such an unequalled distribution of honours”[5]. Murray’s commander, Major William Eames, was later appointed Companion of the Order of Bath for his service in South Africa. In his entry for the action at Reitvlei, Murray tells of Eames’ selfless attempt to retrieve wounded men from enemy-occupied territory.

“We left Pretoria on the 4th [… and] Then we went to Reitvlei […] Here we remained nine days […] and we had a five days [sic] fight with the Boers. The first day the Imperial Light Horse got in a fight which resulted in them having ten killed & 33 wounded. Several of these were left on the positions the Boers took from us. Major Eames and a party with two Waggons went out for them but were detained that night by the Boers [...] We did not hear anything of them for 3 days.” […]

Perhaps most inspiring, however, is the instance in which Murray recounts the willingness of the entire medical staff to take their place in the frontline fighting.

[…] “Next morning early (16th [July]) the Boers made a fearce [sic] attack on our outposts & succeeded in driving them back at one place. […] At about 4pm things looked so critical that Major Rankin of Gen. Hutton’s Staff rode into Camp and came to the Hospital and asked for volunteers from our ranks who were willing to throw off the Red Cross & take their place in the fighting line, as the Boers were expected to break through our lines at any moment. With the exception of four of the Bearer Company, all to the number of 40 Volunteers.”

A FINAL ACCOUNT

As is sadly and often the case, the most complete account of the fullness of one’s life is provided only at one’s obituary. Indeed, on 2 October 1935, the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miner’s Advocate published a comprehensive obituary for Irish-born Murray, who had passed away the month before aged 74 years. Here, Murray is celebrated as a militia man, whose original membership with the 4th (Newcastle) Infantry Regiment ultimately resulted in 38 ½ years of service. He is distinguished also for his foundational membership to the Naval, Military and Veteran’s Association, among other well-regarded organisations.

His active service in South Africa under Major Eames is particularly highlighted for his gallant rescue of wounded men under fire near Machadorp on 13 October 1900. Astonishingly, Murray does not write of any official mention (likely in orders or else in official despatches) in his diary. He does, however, provide a particularly humble version of his part in the action at Geluk, near Machadorp on 13 October.

"The Boer’s sounded Reveille for us this morning by dropping a couple of shells into our camp quite close to our Waggons. Soon all was astir with excitement. No need of the orderly Sgt calling us Before we could get our tents down, shells were falling thick and fast […] soon we had the Carts & Transport Waggons out of the way & had our Ambulance Waggons ready for the wounded. And it did not take us long to fill as the men fell fast. I and 3 others and a Sergt went out to the fighting line & brought in several men, the bullets falling thick around us all the time. At last we had to retire to Dalmanutha."

While Murray’s wartime service was not necessarily celebrated by the Australian public, his bravery and devotion to duty certainly could have inspired his own son, Private Andrew Murray, 35th (Newcastle’s Own) Australian Infantry Battalion, to embark on active service during the Great War, 1914-18. Regrettably, while serving on the Western Front, Andrew Murray was severely wounded in both legs, and was returned home an invalid in January 1919.

It is our fundamental aim at the Anzac Memorial to ensure that the personal stories of the men and women who embarked from New South Wales for overseas service be told in a way befitting of their service and sacrifice. Today, we remember the outstanding bravery of Major General Sir Neville Howse VC, KCB, KCMG, FRCS and, through his preserved diary, that of 381 Private Patrick Murray, NSW Army Medical Corps, and of his son, 7086 Private Andrew J. Murray, 35th Battalion, AIF. Lest we forget.

Article by Jacqueline Reid

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Craig Wilcox, ‘Colonial Wars’, in In That Rich Earth, Brad Manera (ed.), Craig Wilcox and Chris Clark, Trustees of the Anzac Memorial Building, 2020, p. 31.

[2] Excerpt from The London Gazette, 4 June 1901, p. 3769.

[3] ‘A V.C. hero’, Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, 6 June 1901.

[4] Pembroke Murray, Official records of the Australian military contingents to the war in South Africa, 1899-1902, Compiled and edited for the Department of Defence, 1911, p. 14.

[5] Pembroke Murray, Official records of the Australian military contingents to the war in South Africa, 1899-1902, Compiled and edited for the Department of Defence, 1911, p. 13.