In mid-1942 the war in the Pacific was approaching a decisive point. Japan’s sudden attacks on the European empires of Asia had brought about the conquest of almost all of south-east Asia. But Japan’s surprise attack on America’s naval base at Pearl Harbor in December 1941 had not destroyed its capacity or will to resist. Allied and Japanese fleets faced each other in the Pacific and in the Indian Oceans.

Submarines and Japanese naval strategy in the Pacific

Japanese naval strategists knew that its naval forces confronted a large and powerful American fleet in the central Pacific, and that climactic clashes must come soon. In May 1942, they decided to try to distract their opponents by launching raids, on the British in the Indian Ocean and the Americans in the south Pacific. Using ‘midget’ submarines they launched simultaneous raids, on the British anchorage of Diego Suarez in Madagascar on 30 May, and on Sydney Harbour on the following night. Both were intended to distract and disrupt Allied naval forces contesting further Japanese operations in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

The Type-A Ko-hyoteki class submarines were transported to their attack stations close to their targets by large ‘I class’ submarines as deck cargo. (Despite their popular name, they were hardly midgets – they were 23.9 metres long.) Each was armed with two torpedoes. Though they are often regarded as ‘suicide weapons’ they were completed to a high standard of engineering, and not as ‘throw-away’ weapons, but their crews, like all Japanese fighting men, were prepared to die in striking the emperor’s enemies.

In the attack on Diego Suarez a British battleship, HMS Ramillies, was damaged and a tanker sunk, but all of the crews of the two Japanese submarines died. Although it occurred almost 24 hours before the attack on Sydney, no word of warning was sent to other Allied bases – the Allies had no warning of another operation, 10,000 kilometres to the east.

Sydney as a target

Unaware of the crucial advantage the Allies possessed in their ability to break Japanese codes, Japanese commanders naturally sought to distract Allied strength, especially away from the vital central Pacific theatre. Accordingly, the Japanese planned an attack on Sydney Harbour, intending to lead the Americans to divert warships from the central to the south Pacific. Daring (and largely undetected) reconnaissance flights over Australian cities, including Sydney, by float-planes carried by large submarines, confirmed Japanese staff officers’ belief that Sydney was a major Allied naval base worth attacking. They reasoned that sinking a large Allied warship inside the harbour would not only lead American naval commanders to weaken its central Pacific fleet to meet a potential threat off Australia, but that it would also demoralise Australian civilians.

The Japanese plan was to launch three submarines off Sydney Heads and, after penetrating the anti-submarine boom laid across the harbour mouth between Green Point and George’s Head, to sink as many ships as possible. While it seemed unlikely that either the submarines or their crews would succeed or escape, the risk seemed justifiable.

Although it housed a major Allied naval base (with 20 warships at anchor) within a capital city, Sydney was poorly defended. Its anti-submarine detection ‘loop’ system was unserviceable and unmanned, its harbour patrol force was small and inadequately armed, and communications on a dark winter night were unreliable.

Japanese submarines in Sydney Harbour

The attack flotilla arrived off Sydney undetected on 31 May and after 5pm launched three smaller Type-A submarines, known as Ha. (Japanese and Allied identification has been confused over the years but they comprised Ha-14 (Lieutenant Kenshi Chuman), Ha-22 (Lieutenant Keiu Matsuo) and Ha-24 (Sub-Lieutenant Katsuhisa Ban), each with one other crew member. Two of them succeeded in sneaking through the boom net (one trailing a Manly ferry), closely following a vessel passing the opened boom, although one (Ha-14) became entangled and was seen around 8.15pm by Jimmy Cargill, a Maritime Services Board watchman in a rowing boat.

Despite its discovery, the harbour’s defences were activated only tardily. The naval officer in command, Rear Admiral Gerard Muirhead-Gould, issued a vague warning order at 10.27pm. The discovery of Ha-14 in the net took an hour-and-a-half to be confirmed, and even after naval officers knew that enemy submarines were in the harbour, civilian ferries continued to operate fully illuminated. Even after unarmed patrol craft spotted and warned of submarines (and even rammed one) the defenders reacted lackadaisically. Caught in the net, Lieutenant Chuman scuttled Ha-14 at 10.37pm. One minute before, naval headquarters at Garden Island had issued a second general alert.

The other two submarines, Ha-22 and Ha-24, proceeded into the harbour (moving at about three to five knots to conserve their electric batteries). Royal Australian Navy patrol craft raced about the harbour searching for sight of their periscopes or the sound of their propellers. They dropped depth charges, alerting Sydneysiders that their harbour had become a battlefield. Despite the sound of explosions and gunfire, neither Muirhead-Gould nor the senior American naval officer in Sydney, Captain Howard Bode, reacted decisively, partly because naval communications broke down, but also because neither could believe that the Japanese could have penetrated the harbour.

For several hours the two remaining submarines moved about the harbour, sought by anti-submarine craft. At last, at about 10.50pm, Ha-24 reached a position off the naval base of Garden Island. Lieutenant Ban saw through his periscope the bulk of the American cruiser USS Chicago silhouetted about 500 metres distant against the floodlights illuminating the construction of the island’s dry dock. Hitting the cruiser was the aim of the entire mission. Deterred by fire from the Chicago (whose lookouts had spotted the sub’s conning tower) Ha-24 submerged near the harbour bridge.

Photo: The aim of the entire mission. USS Chicago in Sydney Harbour at the time of the attack by Japanese submarines. AWM P00279.004.

Sinking of HMAS Kuttabul

From a position off Bradley’s Head, at about 12.29am, Ban fired the first of two torpedoes at the Chicago and within a minute another. Both missed and instead hit Garden Island, the second without exploding, but the first detonated against the sea wall beneath HMAS Kuttabul. The converted Sydney Harbour ferry (and later a ‘concert boat’) had been taken over by the Royal Australian Navy as a depot ship. The explosion lifted the Kuttabul out of the water and it quickly sank. The blast killed twenty-one sailors in the ship, nineteen Australian and two British.

Photo: Upper deck of the damaged, partly submerged HMAS Kuttabul. AWM 012427.

Having fired its two torpedoes, Lieutenant Ban’s Ha-24 submerged and made for the harbour mouth, leaving by about 2am. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Matsuo’s Ha-22 lay on the harbour bed just inside the anti-submarine net, awaiting an opportunity to find and fire at an Allied warship. At 3am Ha-22 began to move towards the harbour bridge, searching for the larger warships believed to be in port.

The sound of firing, depth charges, the scuttling of Ha-14 and the explosion which sank Kuttabul contributed to the confusion and chaos on and around the harbour. Warships fired at shadows and supposed sightings, searchlights probed the sky, and many Sydneysiders panicked, understandably assuming that the long-anticipated Japanese invasion had begun. In the absence of any official information or reassurance, wild rumours spread. Five hours after Jimmy Cargill, the Maritime Services Board watchman had seen Ha-14 caught in the net, Admiral Muirhead-Gould at last confirmed that Japanese submarines were indeed in the harbour.

Allied naval forces respond

By the early hours of 1 June, Sydney’s defences were at last responding coherently, particularly the small auxiliary launches equipped with depth charges which criss-crossed the harbour all night. Several, Steady Hour and Yarroma, and especially Sea Mist, played a vital part in destroying the third submarine.

At some point, Matsuo’s Ha-22 tried but failed to fire its two torpedoes – it had been damaged either by depth charges or by colliding (possibly with Chicago as it left the harbour). Matsuo appeared to have moved to the sheltered water of Taylor’s Bay to attempt to free the torpedo release gear. The patrolling Sea Mist, under Lieutenant Reg Andrew, saw and depth-charged it, and the submarine rose to the surface, inverted. (Andrew reported seeing signs of three submarines, which was impossible, but one was probably a harbour buoy dislodged by the depth charge, and the ‘other’ part of the one submarine, broken up in the attack.) Though Sea Mist had probably disabled Ha-22 with its first depth charge, other patrol boats (believing that more submarines were about) continued to drop depth charges in Taylors Bay for several hours. Sadly, competing (and mistaken) claims were to deny Reg Andrews the credit he deserved. The submarine’s two crewmen, refusing to emerge and surrender, died at their own hands.

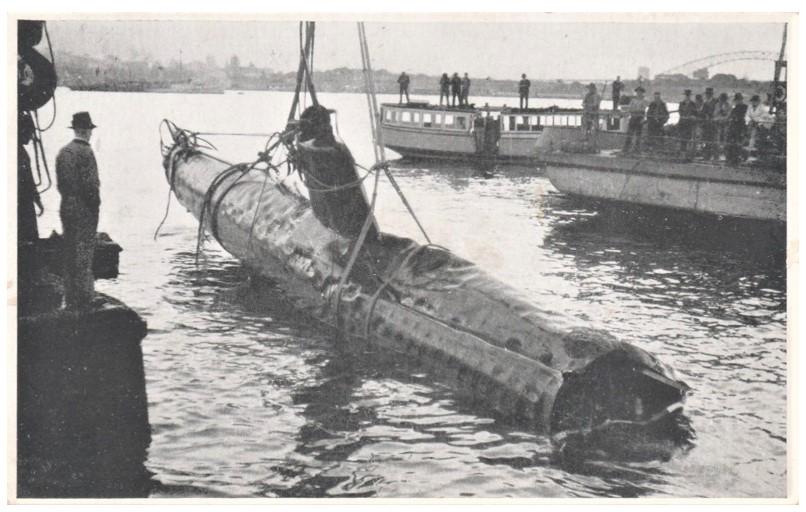

Image: A souvenir postcard of the midget submarine skippered by Lieutenant Matsuo Keiu raised from the floor of Taylors Bay in Sydney Harbour. Matsuo and his navigator suicided when it became obvious that their submarine could neither fight nor escape. Anzac Memorial Collection.

Photo: Matsuo’s Japanese midget submarine being raised by a floating crane from the floor of Taylor’s Bay. AWM 305088.

As it became clear that the raiders were destroyed or gone, Sydney returned to normal life, although censors temporarily forbade any mention of an attack which much of Sydney had heard or witnessed. Official enquiries disclosed how shambolic the defence of Sydney had been. Only Kuttabul had been sunk, but two cruisers, Chicago and Canberra, had been spared more by luck. At least twenty-five men had died so far in the raid – twenty-one from Kuttabul and the crews of the two submarines that had been recovered. On 9 June, the bodies of the four Japanese sailors were cremated with full naval honours. The Australian authorities hoped this gesture of respect would ameliorate the treatment of the thousands of Australians in Japanese hands. Though appreciated by the Japanese government, it was to make no difference to the treatment of prisoners in remote jungle camps.

Continued attacks on the NSW coast

In the week after the raid, Japanese submarines attacked ships off the NSW coast and fired shells, ineffectually, at Newcastle and into Sydney’s eastern suburbs. The attacks reminded Australians of their vulnerability and of how the anticipated invasion remained a possibility, even though the Japanese had decided not to pursue the option of invasion.

Lieutenant Ban’s Ha-24 had left Sydney Harbour as it had arrived, undetected, and it subsequently disappeared. None of the three intruders returned to the mother submarines. Ha-14 had become entangled in the net and Ha-22 had been depth-charged in Taylor’s Bay. For a further 64 years Ha-24’s fate remained unknown. In 2006, however, recreational divers discovered the wreck of Ban’s Ha-24 lying three kilometres off Newport on Sydney’s Northern Beaches. This was north of The Heads and in the opposite direction to the submarines’ planned rendezvous with the mother ships – not the least of the raid’s remaining mysteries. Its discovery did not explain the fate of the crew who must have perished, though in what circumstances is unknown.

Though the raid embarrassed Allied commanders, worried the Australian government and frightened many Australians, all too aware that Japanese raiders had penetrated into the heart of Australia’s largest city, the attack failed almost entirely. Allied codebreakers had already ensured that American naval commanders would not be distracted from the desire to engage the Japanese. Later in June, US and Japanese fleets clashed in the Pacific in the decisive battle of Midway which, by sinking Japanese aircraft carriers, destroyed the Japanese capacity for further offensive action. Though peripheral to the larger war in the Pacific, the raid on Sydney Harbour remains central to the story of Sydney’s war.

Recommended reading

Several books have been published on the raid. The official history (published in 1968) contains several errors, and its widely reproduced maps of the raid have been criticised as misleading.

The most comprehensive accounts of the attack are by Steven Carruthers, who published two books, Australia Under Siege, in 1982, and Japanese Submarine Raiders, in 2006, while the best single book (which deals fully with various mysteries, some still unsolved) is Peter Grose’s A Very Rude Awakening (2007). Peter Stanley’s Invading Australia (2008) provides useful context on Australian fears of invasion.