6th August, 1915. We charge Lonesome Pine this afternoon. The bombarding has been going on all day. It is now three o’clock. We are all in battle order and have to move up in one hour and a half.

5 o’clock. The bombarding is terrible now. We charge in half an hour. My thoughts are of home. I wonder will I live through. I have a big lump in my throat.

5.25. Five minutes and we charge.

— Excerpt from the diary of Private James Smith, 3rd Btn (Anzac Memorial Collection 2020.30.4)

At 5.30pm on 6 August 1915, the NSW-raised 1st Brigade charged across the 400 Plateau towards the Turkish trenches at Lone Pine. Through the bloody fighting, the men eventually succeeded in penetrating the enemy’s heavily fortified trenches. By nightfall, the Turkish frontline was in Australian hands.

At once, the Turks launched a fierce counterattack.

“For almost four days men threw grenades and shot each other at close range. Both sides were reinforced. Eventually, the Australians held the positions they had captured”.[1]

Private James Smith, whose diary provides a comfortless countdown to the moment of the charge, was landed at Gallipoli on 13 July 1915. Though he ultimately survived the battle, Smith was severely wounded in the early morning of 10 August 1915, when a Turkish bomb ripped through his left knee. He documents his last days at Gallipoli in three succinct yet sobering entries.

8th August, 1915. We had terrible losses in the charge. I am still alive but very full of the sights I have seen these last two days.

9th August, 1915. Cannot write, the Turks are attacking.

10th August, 1915. Stopped one this morning at 6 o’clock, leave here to-night for England.

Suffering grievous wounds, Smith was immediately evacuated to the beach and embarked for No. 3 Australian General Hospital at Mudros, and thence to England.

And so ended his swift and pitiless experience of the frontline fighting. And yet, for Smith — as for so many others — the war was far from over.

A PRINTER FROM HURSTVILLE

James Smith was just 21-years-old when he enlisted as reinforcements to the 3rd Australian Infantry Battalion on 26 January 1915. A labourer printer with no military experience, Smith could have hardly anticipated the grim realities of modern warfare. Indeed, before embarking for Egypt via the “Man o’ War steps” at Circular Quay, Smith’s world was confined largely to the bounds of his birth town of Hurstville, New South Wales.

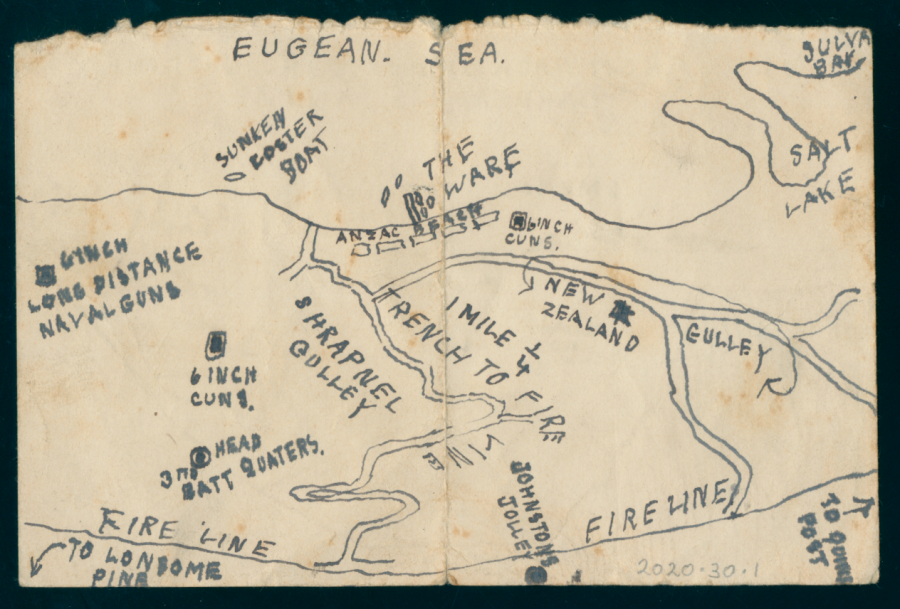

Smith’s collection of Great War memorabilia was donated to the Anzac Memorial in 2020 by his great niece, Sue Blaxland. His diary and sketches in particular offer a fascinating lens through which to examine the wretched existence of the men at Gallipoli in weeks preceding the August Offensive.

His diary begins on the night of 13 June 1915, on board a minesweeper just off Anzac Cove.

THE BEACH

“The first sign of battle was the zip zip of stray bullets. […] As we were fully equipped with all our issue and added to this 250 rounds of ammunition we had no light weight to carry, and found it hard to keep from falling overboard, especially as our feet had no grip on the slippery planks of the barges. After a lot of bumping about we ran alongside another barge, it having been sunk by a Turk’s shell and now used as a wharf. We went along the well-known Anzac Beach for 300 yards then we got the order to lay down and sleep. It was 1.30am when we got to sleep and 4.30am when we were awake again.”

By the time Smith landed at Anzac, the beach provided a vast and organised system of medical stations, ordnance stores and supply depots, whose ceaseless operations—though continuously hindered by enemy fire—supplied care, ammunition, water, food and basic comforts to the men. As official war historian Charles Bean described it:

“The shoreline itself resembled rather an old-time port, with its crowded barges (often beached to prevent their being sunk), a few short piers, piles of biscuit boxes and fodder stacked behind, the smell of rope, of tar, of wet wood, of cheese and other cargo: but in the water the hundreds of bathers, and on the hillside the little tracks winding through the low scrub, irresistibly recalled the Manly of New South Wales or the Victorian Sorrento, while the sleepy 'tick-tock' of rifles from behind the hills suggested the assiduous practice of batsmen at their nets on some neighbouring cricket-field.”[3]

Indeed, the tantalising prospect of a swim at ‘Manly’ proved irresistible to Smith in the afterdays of his arrival in the trenches. He recounts his first and only dip in the sea with an amusing degree of nonchalance.

“Three of my mates and myself off for a swim, ¾ of a mile to the beach. On reaching the beach we stripped off and in two ticks we were ducking each other and trying to make our miserable life happy. We hardly had time to wet ourselves when whiza shell popped into the water alongside a steam launch about 500 yards away. 'Come on Jack they are off'. As quick as possible we got out of the water and got behind a big stack of bully beef cases. Sitting as comfortably as possible we waited for the next shell. We did not wait long but when it came it landed right on our stack of bully beef and all of the bully beef it was everywhere. 'Come on' said my mate, time we shifted and in about a half a second we were getting up the hill with our clothes under our arms.”

Within days, swimming at Anzac was prohibited when, according to Smith, 18 bathers were killed or wounded by the explosion of one Turkish shell.

THROUGH THE PERISCOPE

A great portion of Smith’s brief diary is dedicated to his time observing the enemy. Compelled into the firing line on the day of his arrival, Smith experienced the biting severity of trench warfare from the outset.

“I had been observing about an hour and a half when I noticed something moving behind the Turks’ trenches. I drew the Corporal’s attention to it and he in turn informed the bomb station. After I had been waiting a little while longer, I notice[d] the moving about of a straight trail of fire like a sky rocket makes. It stopped in the air over the spot I had been observing. I could now hear a ‘whp whp’ and there was a terrible explosion. When the smoke cleared away I noticed there was a big gap in the Turks’ trench and the spot I saw the caps was altered that much that you would hardly know it again. I turned and asked the Corporal what sort of a gun it was and he said 'A gun, why that was a Japanese bomb'. The Turks didn’t appreciate this bomb and for the next hour we were kept busy dodging their shell and shrapnel.”

On another occasion, Smith recounts his near rendezvous with death.

"6th July, 1915. Just out of the firing line. Last night we blew up one of our saps under the Turks’ trenches and did a considerable amount of damage. I had a narrow escape this morning. I was observing through a loophole it not quite being daylight; the corporal came and told me to hop down as I was Mess Orderly, and told Jackson to take my place. Jackson hopped up, looked through the loophole and got a bullet through the head, killing him instantly. Nothing else important."

THE HARSHEST OF CONDITIONS

With a surprisingly dry humour, Smith relates some of the small comforts afforded him. From “Bully Beef stew” to “those hard ships biscuits, the ones you have to break with a pick”, Smith’s breakfast menu is seamlessly interwoven into many of his otherwise bleak entries.

4th July, 1915. We have just had breakfast with biscuit and bully and a mouthful of rank cheese and enjoyed it. It has been raining all night and the trenches are in a frightful mess. We are wet through and the trenches 6 and 7 inches with mud. Our blankets which we got a couple of days ago and our clothes are thick with mud. We have to keep digging the sides of the trenches which keep falling in. We can still hear them bombarding the big hill, “Achi Barba”. The sun just came out so I will finish for the time being as I want to dry my things.

5th July, 1915. Just out of the firing line. It is still raining on and off, I never felt better in my life. Just had a breakfast of bacon fat and biscuit, and cold tea with no sugar in it. The Turks are firing a big new shell. It is about 2 feet 6 inches long and one across; it shakes the whole place when it bursts.

However, in some instances, the day’s events are simply too joyless to warrant any mention of breakfast.

“I have now been 13 days in the trenches and present an awful picture. Have not shaved for two weeks, have not had a wash for a week. I feel dirty and my clothes are thick with dirt. We are not allowed to go for a swim on account of the enemy shells. One shell wounded 18 men yesterday. We expect an attack and have to stand too [sic] at all hours and times. After 18 hours in the firing line we are put on digging trenches, the sun near roasts us. One of my mates just gone to the hospital with a big piece of shrapnel in his side. Digging trenches we often come across the body of a soldier, rotten and decayed, and the smell awful. Sometimes a man’s leg or arm. I am absolutely sick of the whole thing. I long for Sunny New South Wales and home. I have to form in for two hours drill now amidst shot and shell.”

THE UNWRITTEN STORY

Smith’s diary ends with his being wounded on 10 August 1915, though he was not formally discharged until 18 October 1916. Astonishingly, it was not his knee injury that ultimately saw him returned to Australia and deemed medically unfit for service. In fact, it was the result of an amputated right forefinger.

The period of Smith’s convalescence in England is not well documented in his service record. We know that Smith was admitted as a surgical patient to the 5th London General Hospital (St Thomas’ Hospital) on 30 August 1915. Presumably, by January 1916 he was fit enough to be granted leave as, on 24 January, Smith presented as suffering an undiagnosed venereal disease. His treatment was lengthy and likely painful, and his pay forfeited throughout.[4]

Venereal disease was a common affliction among the Australians on leave or in training in Egypt, England and France. Indeed, by war’s end, some 60,000 men had succumbed to some form of venereal infection; approximately 12 per cent of the total number who enlisted.[5] Understandably, though perhaps not entirely sympathetically, the senior ranks of Australia’s Imperial Force were altogether intolerant of the spread of VD. Before and during the Gallipoli campaign, men suffering VD were quickly and quietly returned to Australia. However, by January 1916, most were kept overseas, and sent for treatment at the 1st Australian Dermatological Hospital in Bulford, England.[6]

Though we do not know where Smith received his treatment, by March 1916 he was considered well enough to join the Australian and New Zealand command depot at Weymouth, England. His recovery from whatever disease had ailed him, in concert with the authoritative advice that he was recovered from his wounds, surely destined Smith for the Western Front.

But this was not the case.

We may not ever know the circumstances surrounding the wounding and subsequent amputation of Smith’s forefinger. Whether an accident of training, or something else entirely, the cause of the injury is altogether irrelevant. What remains relevant is that, at just 21 years old, a young and bold Smith volunteered for active service overseas, forever changing the course of his life.

Following his discharge, Smith returned to printing, and eventually came to work for the Government Printing Office in New South Wales. Regrettably, Smith never reached old age. Unmarried and childless, he died on 3 August 1949, aged 55 years. Just as his diary intimates, his experience at Gallipoli and, indeed, during the Battle of Lone Pine never truly left him. Lest we forget.

Article by Jacqueline Reid, Exhibitions Research Officer, Anzac Memorial.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Brad Manera, In That Rich Earth, published by the Trustees of the Anzac Memorial, Sydney, 2019, p. 53.

[2] Andrew Grey, ‘Courage at Lone Pine’, Australian War Memorial website, https://www.awm.gov.au/wartime/34/article, 30 March 2021, accessed on 19 July 2021.

[3] Charles Bean, ‘The Beach’, Chapter XII, Volume II, The Official History of Australia in the Great War of 1914-1918, 11th edn., Australian War Memorial, 1941, p. 346.

[4] A Military Order of February 1915 deemed VD patients as absent from duty and so their pay (including the portion allotted for their families) was stopped. M. Lewis, Thorns on the Rose, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1998, p. 158.

[5] Ibid, p. 157.

[6] Craig Tibbitts, 'Casualties of War', Australian War Memorial website, 30 March 2021, https://www.awm.gov.au/wartime/article2, accessed on 19 July 2021.

![2019 Private James Smith, 3rd Battalion, AIF, sometime after enlisting, [Sydney], c. 1915. Gift of Sue Blaxland. (Anzac Memorial Collection 2020.30.32)](/sites/default/files/styles/anzac_slide/public/Private%20James%20Smith%20in%20uniform%2C%20c.%201915.png?itok=RG6BxDXN)