Vomit, diesel fumes, and salt spray. The sound of bullets splintering timber, ricochets off steel and the slap of rounds striking flesh. The juddering thump of waves hitting the slab sides of a flat-bottomed boat. And above all the sensation of urgency inspired by revving marine engines. The squeal and clank of winding gear and the shock of bullets zipping by or blood and groans as they strike home.

These are the adrenalin pumping scenes that the Hollywood A-Team of Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg gave us of D-Day. That action-packed 20 minutes at the start of their epic film Saving Private Ryan. It is the mental image most Australians have when the term D-Day is mentioned.

Saving Private Ryan was made in 1998 and in 2014 it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as “culturally historically or aesthetically significant.”

Any historical film is going to attract critics, so I am not going to comment on the level of historical accuracy of Saving Private Ryan. I am not going to note that the US M-1 helmets they were wearing did not appear to have fixed bales or that many of the beach obstacles faced the wrong way.

My interest is in the Australians who were caught up in that longest of days and the fighting that followed - the campaign to rid Europe of Nazi domination.

The landing and the offensives that followed were codenamed Operation OVERLORD. It lasted from 6 June to the fall of Paris in late August 1944.

While Saving Private Ryan offers an interpretation of the experience of a company of US special forces from 2nd Ranger Battalion operating alongside the 29th US (Infantry) Division as they attack the Dog Green Sector of Omaha Beach, they were but a small contingent of the almost 160,000 Allied sailors and soldiers to hit five beaches across the Normandy coast. The beaches ran from the base of the Cotentin Peninsula in the west to the fishing village of Ouistreham in the east.

We know that over 3,000 Australians were involved in Operation OVERLORD.

What I would like to discuss are the events of 6 June 1944 in Normandy and the course of the campaign then offer some case studies of the Australians who were there.

I will highlight those whose stories are told here at the Anzac Memorial and conclude with some views on how D-Day has been remembered over the past 80 years.

D-Day, the term and its association

D-Day is a simple military term for the day of the commencement of an operation or exercise but for generations, since 6 June 1944, the word D-Day has evoked images of the Allied landings in Normandy. It was one of the largest and riskiest, certainly the most famous, amphibious operation in history.

OVERLORD was the umbrella title for a diverse range of lesser operations, with particular and specific tasks, on land, sea and air, as well as covert intelligence deception operations, all working towards achieving the opening of a second front by the Allies in western Europe and the eventual defeat of Nazi Germany.

It was a daunting, indeed forbidding, task. It has been, and continues to be, studied, dissected and analysed.

The war in 1944

To put it all in context let's start with a brief recap.

Shortly after the evacuation from Dunkirk, British and Allied units had begun to launch raids on the European continent. In August 1942, the British used the Canadian Division to attack the French port of Dieppe. It was a slaughter. The Canadians suffered almost 70% casualties. Few got off the beach. It was a tragic demonstration of just how formidable the Nazi’s defences of Fortress Europe were.

On the eastern front the Soviet Union’s Red Army had been forced back to the gates of Moscow but by 1944 their counter offensives were clawing their way forward at great cost in blood and materiel.

Attacked by the Japanese, the US entered the war in December 1941. It mobilised its forces and restructured its economy to become the ‘arsenal of democracy’.

In 1943 the course of the war began to change in the Allies favour. The Axis suffered major defeats beyond Europe and the Allied bomber offensive was destroying German industry and morale.

The US government had made a commitment to Britain and the Soviet Union that they would help defeat Germany first. US military leaders advocated a direct attack on western Europe as soon as possible. The Soviets were just as impatient. The British however, haunted by the experience of Dunkirk and Dieppe, and memories of Gallipoli from the Great War, urged caution. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Channel, the German High Command prepared for the predicted attack.

The German High Command (the OKW) knew the attack must come - but where?

Fortress Europe

Hitler decided to build coastal fortifications running from Scandinavia to the Bay of Biscay. He declared this Atlantic Wall would protect ‘Fortress Europe’. It was a vast and complex undertaking. Hundreds of German engineers from the Organisation Todt (OT) led teams of private contractors with specialist skills and hundreds of thousands of slave labourers conscripted from the occupied countries. The construction consumed vast quantities of essential materiel as well as systems and supply chains like road and rail transport, storage and handling facilities.

The Atlantic Wall included casemates that mounted coastal guns as large as 380mm calibre down to 37mm anti-tank guns. Concrete or steel pillboxes protected machine guns. Observation posts of every variety housed rangefinders large and small. Bunkers were built for everything from headquarters to stables. They were small cities underground. Above ground there were early warning radar stations, anti-aircraft batteries and searchlights.

By early 1944 the principal sector of the wall, had been placed under the command of the legendary German Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel.

A veteran of the Great War Rommel had earned a reputation for courage and innovation on the battlefield. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, the Balkans and the Italian Isonzo Front during the 1914-18 War, he enhanced his reputation while commanding a Panzer (tank) division in Belgium and France in 1940 and became known to Australians as the head of the German Afrika Korps in North Africa from 1941 to ’43. After the fall of Tunis however, Rommel was worn out.

Once a devoted follower of Adolf Hitler Rommel watched the fruits of hard-won victories lost by the Fuhrer’s increasingly ill-considered, often illogical, decisions. Taking up his new post in northern France in 1944 he soon realised that the Fuhrer’s boasts about the impregnable Atlantic Wall were nonsense.

The wall was incomplete. German weapons were in short supply. Worn-out, captured equipment, with limited ammunition supplies, were installed in their place. The coastal defence regiments had been stripped of their fittest men, redeployed to the Eastern Front as replacements for the crippling losses the German forces were suffering at the hands of the Red Army. There were troops manning the defences who had been conscripted from the occupied territories, troops of questionable reliability.

Rommel reviewed his resources. He had seen the effectiveness of uncontested Allied air forces in Africa. He knew they could destroy or disrupt troop movements on or behind the battlefield.

Rommel believed that his only chance of victory over a massive Allied invasion force was to stop them at the water’s edge and drive them back into the sea. He wanted his strength to be in or near to those coastal fortifications. He believed the first 24 hours would be critical. It would be the longest day.

More senior members of the OKW in the west disagreed. They insisted that the most mobile force in northern France, a handful of elite German Army and SS Panzer divisions [including the reconstituted 21st Panzer Division (with few of its North Africa veterans left), 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend and the Panzer Lehr Division], should be held back from the most forward areas so that they could assess the strength of the attack, evaluate whether it was a feint, then deploy to where the genuine enemy threat was evolving.

Hitler intervened and insisted that, in the event of an invasion, half the Panzer force would deploy only on his direct order. To make this command situation even more confusing Rommel had little or no direct control over Luftwaffe or Kriegsmarine assets in the area.

Invasion preparations

Allied preparations for the invasion were monumental. Years in the planning, coordination and problem solving, an international force of several million were brought together, housed, fed, clothed, armed, trained and rehearsed in an almost infinite range of skills and tasks. The logistics labyrinth to acquire, transport, store and distribute everything from bombs to military pattern prophylactics for Operation OVERLORD was enormous.

A commander had to be chosen. There were many contenders but as most of the assault force were American a US officer was appropriate. The initially unlikely, but in retrospect the wisest choice, a choice made by President Roosevelt himself, was General Dwight D Eisenhower. Eisenhower had experience of amphibious operations in the Mediterranean in 1943. Most importantly, he had the diplomatic skills to manage the multi-national undertaking. There was the political meddling of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the egocentric behaviour of the senior British general, and boyhood piano player on a Murray River paddle steamer, Bernard Montgomery, as well as mercurial performances by other subordinate commanders in each of the branches of service to contend with.

Montgomery was given command of the land forces for OVERLORD and the former boilermaker and US general with the soldier’s touch Omar Bradley was to command the 1st US Army, the men who were to storm Utah and Omaha Beaches.

There were landing sites to be selected. The Pas-de-Calais was the obvious choice. It was close and it had a port. Of course, the Germans knew this and so had fortified the area heavily. Generaloberst Hans von Salmuth’s crack 15th Army was stationed in and around the port and coast, with defence in depth as far as Lille!

Cherbourg was another port with possibilities but, situated at the end of the Cotentin Peninsular, it would have been too easy for the enemy to isolate it. Le Harve, was also considered because its coastal cliffs and inland rivers were obstacles that favoured the defenders. The ghosts of Dieppe ’42 may also have had an influence.

That left the coast of Normandy from the mouth of the Orne River in the east to the base of the Cotentin Peninsular in the west.

The Allied plan divided the area into five landing zones. From west to east the first were the US beaches codenamed ‘Utah’ and ‘Omaha’, then the broad British ‘Gold’ Beach, the Canadian Beach codenamed ‘Juno’ was further east, and the fifth, a largely British, with some Free French units, zone called ‘Sword’ Beach culminating in the fishing village of Ouistreham.

Each of the beaches were subdivided into sectors named using a phonetic alphabet. Behind the beaches three airborne divisions, the US 82nd and 101st and the British 6th, were to jump in or land by glider the night before the dawn landing to secure bridges and road junctions inland. The tip of the Allied spear would comprise almost 160,000 assault troops on the first day, a quarter of a million by the first week.

Deception to divide German defensive strength was essential and one of the great success stories of OVERLORD. British counterintelligence created schemes that presented the Germans with possibilities that the invasion could begin anywhere from Norway to the south of France. The Germans were so convinced by the Allied creation of a fictitious army around Dover that included inflatable dummy tanks, empty tent cities and bogus radio traffic that they retained their strongest defences in the Pas-de-Calais. The deception was reinforced by ensuring that the Allied bombing of coastal defences and aerial photo reconnaissance sorties did not concentrate solely on Normandy. The ultimate deployment of German defences and responses by the OKW on 6 June 1944 demonstrate the success of the Allied deception and an extraordinary failure by enemy military intelligence. Even after the initial landings in Normandy the OKW suggested they were a feint, and the real invasion would hit near Calais!

A remarkable aspect of OVERLORD were the innovative solutions to problems. A harbour with dock landing facilities was essential for an operation of that size but something that the selected section of coast lacked, so two portable floating harbours were designed. Codenamed ‘Mulberry’ they could be towed across the channel and sunk in place, one for the US at Omaha the other for the British at Gold. (Remains of the British Mulberry harbour can still be seen at Arromanches.) To provide essential fuel for tanks, trucks and other military vehicles a pipeline from Britain, under the channel, to France was designed. Codenamed Pluto (for ‘Pipeline Under The Ocean’), it meant petroleum supplies could not be interrupted by bad weather or air attack.

With impressive ingenuity and drive Pluto was ready for D-Day and, after Cherbourg was captured and sea mines cleared, it was operational by August. (A member of the crew with the complex and risky task of laying Pluto from HMS Sancroft was 22-year-old Lieutenant Lyle Clark Miller from the Adelaide suburb of Henley Beach. After the war he souvenired a section of Pluto. It is in the collection of the Australian War Memorial.)

For the battlefield the British designed weapons to overcome the unique challenges of this amphibious landing. Under the supervision of Major-General Percy Hobart these weapons included tanks that could ‘swim’ from landing ships to the beaches, tanks that mounted huge flails to detonate land mines in their path, tanks equipped with flame throwers and command detonated demolition charges, tanks that mounted large bobbins of canvas and steel track to create a path over soft sand and a range of other armoured vehicles that were soon dubbed ‘Hobart’s Funnies’.

Invasion at last

The weather intervened. A massive storm lashed the English Channel. The landing was delayed for 24 hours. In barely tolerable weather on the night of 5/6 June thousands of British and US paratroopers were dropped inland from the landing beaches to secure the flanks and capture bridges. At dawn, with the tide low to expose the obstacles, the landing barges went in. Tens of thousands of men raced across open sands, through minefields and beach obstacles, against withering machine gun and artillery fire, to force their way into fortress Europe!

History remembers the Allied invasion as successful however there were mistakes and failures. The Americans at Utah landed almost two kilometres off course. The assistant divisional commander of the US forces landing on Utah, Teddy Roosevelt, son of the hero of San Juan Hill, on discovering the error is reputed to have made the comment “We'll start the war from here”.

At the other US beach, Omaha, the men of the US 29th and 1st Divisions suffered very heavy casualties by insisting on a direct assault against the strongest German positions on that stretch of the coast. The British and Canadian beaches fared slightly better due to their extensive use of Hobart’s funnies and their ability to outflank the German positions.

The German troops that were garrisoned on the coast frequently found themselves outnumbered however they fought gallantly and demonstrated an extraordinary ability to respond quickly to the evolving tactical situation. The response by their high command was less impressive. Confusion over whether the landings at Normandy were a feint, and the genuine landing would be at a more logical section of the coast, hindered a fully committed reaction and Hitler's reluctance to allow battlefield commanders free use of his armoured divisions helped the Allies establish themselves ashore. Allied mastery of the air meant that any movement in daylight was observed and attacked.

As with any beach landing there is confusion. The confusion slowed the advance. In the US sector the hedges and sunken roads slowed the push inland. In the British sector traffic congestion and indecision was widespread. The major city of Caen, on the eastern flank of the operation, was not captured on the first day as intended.

Through June the British faced the risk of attack from the east. They held the line against heavy German defence and localised counterattacks. By mid-June they had fought through to Villers-Bocage. In the west the US fought their way up the Cotentin Peninsula. They captured Cherbourg by the end of the month.

In July the US went on the offensive. Saint Lo was attacked. The British attacked with Operation GOODWOOD. In the last week of July, the Americans launched the massive Operation COBRA. The flamboyant US General George Patton broke through the German lines and swept south then east outflanking the German defences surrounding them in the Falaise pocket. When the pocket fell 10,000 German dead were counted and 50,000 made prisoner.

By the end of August, the Allies fought their way into Paris. The Normandy campaign was over but it would take until May of 1945 before the final defeat of Nazi Germany.

Australians in Operation OVERLORD

At the outbreak of the war, we had more sailors than ships for them to serve in. Large numbers of RAN reservists were sent to Britain to serve in the Royal Navy. By 1944 many were still there and were distinguishing themselves at sea or in roles like mine clearance. Several hundred members of the RAN saw action on D-Day.

In the run in to Gold Beach landing craft, with men of the 50th British Division, passed the RN frigate HMS Kingsmill. Commanding the guns of A and B turrets was 22-year-old Sub Lieutenant Roy Hall RANVR, of Fremantle. The sailors cheered the men in the landing craft and the soldiers shouted encouragement back. No stranger to amphibious operations Hall had been shot in the arm leading a landing party at Syracuse during the Allied invasion of Sicily. He would always remember the courage of the men in the landing craft on D-Day.

The biggest threat to the British men and ships headed for Gold were the German 155 mm coastal guns at Longues-sur-Mer. Those guns were destroyed and their crews killed by fire from the British 6-inch gun cruiser HMAS Ajax. Hall discovered later that his RANVR mates, Sub-Lieutenants Alf Pearson, a fellow West Australian, and Launceston born Bob Fotheringham were in Ajax. Alf was directing the fire from the ship’s main armament. Alf and Bob had both joined the RAN under the wartime ‘Yachtsman’s Scheme’ and risen to commissioned rank from Ordinary Seamen.

At the eastern extremity of the landings, off Sword Beach, 21-year-old, Melbourne raised, Lieutenant Dacre Smith was serving the great guns aboard the cruiser HMS Danae.

Between the two, at Juno, another of that generation 23-year-old Sub-Lieutenant Bruce Ashton, from Kingsford in Sydney, was commanding Landing Craft, Assault, Hedgehog, 1106 equipped with hedgehog mortars. Running in close to use his mortars to detonate land mines ahead of the infantry his vessel was hit by enemy fire. His body washed ashore at Greye-Sur-Mer. He is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery at Bayeu

Another Australian sailor to die that day at Juno was Victorian, Sub-Lieutenant Richard ‘Digger’ Pirrie. An all-round athlete, Pirrie had played league football for Hawthorne before enlisting. On D-Day he came ashore with the 7th (Canadian) Infantry Brigade in the assault wave. His task was to direct naval gunfire support as a forward observer. Killed by German shellfire, his body was not recovered. It was his 24th birthday.

Among the Australian sailors decorated for D-Day was Lieutenant Commander Ken Hudspeth DSC**. Raised in Tasmania, a keen bushwalker, sea scout and schoolteacher, Hudspeth joined the RAN early in the war and saw sea service on Atlantic convoys before volunteering for ‘special and hazardous service’. He discovered that the ‘special’ service meant almost suicidal operations in the experimental British midget submarines called X-Craft.

Against the odds Hudspeth survived and earned his first Distinguished Service Cross attacking German capital ships in Norwegian fjords in his X-Craft. He earned another DSC on an OVERLORD related mission. Operating with commandos conducting a survey of what would become Utah and Omaha Beaches in January 1944 he and his team were sent to answer questions ranging from confirming enemy gun positions close to the shore to testing the density of the sand on the landing beaches. On 6 June his X-Craft, short of air and at risk of being rammed by the invading fleet, guided the Canadians into Juno resulting in a very rare third DSC.

After Normandy Hudspeth used his submarine experience to combat U-boats on the Artic convoys to Russia. His youngest brother Donald was killed in a Lancaster over Germany in March ’45, eight weeks before the war ended. After the war he returned to teaching, married his English sweetheart and had three sons, the youngest named Donald. In retirement he volunteered at the maritime museum in Hobart. Ken Hudspeth DSC** died in 2000.

By far most Australians involved in Operation OVERLORD were fliers.

RAAF aircrews or lone fighter pilots few sorties in support of sea and ground operations either in Fighter Command, Bomber Command, Transport or Maritime Command.

On the night of 5/6 June RAAF bombers from Article XV squadrons and RAAF aviators crewing RAF bombers in British squadrons attacked German coastal batteries, troop concentrations and transport hubs. Other RAAF aircrew flew the glider tugs that dropped the airborne forces from Pegasus Bridge to the Cherbourg Peninsula. Maritime squadrons protected the invasion convoys. After the beachhead was established, No.453 (fighter) Squadron RAAF relocated to Saint-Croix-sur-Mer on 10 June and later flew from a field behind the remains of the German battery at Longues-sur-Mer.

Among the tragic stories connected with No.453 (Fighter) Squadron is the loss of one of the squadron’s section commanders 27-year-old Flight Lieutenant Henry Lacy Smith of Kogarah.

An experienced and admired pilot Smith had been with the squadron on operations since April. On 11 June he was leading a patrol at 1,500 feet over the beaches from Omaha to southwest of Ouistreham. Just after 8pm Flying Officer David Murray from Brunswick reported that he saw Smith’s Spitfire hit by a burst from a German 20mm flak gun. The aircraft lost height and speed then a trail of “white fume”. They heard Smith’s voice on the radio “I am going to put this thing down in a field.” He did not make it. His fighter belly landed on the waters of a canal, skidded, then rolled over, nose first, and sank. He had not jettisoned his long-range tank or canopy. His mates circled for a few minutes but the enemy gunners had their range and they had to break off and return to their airfield at Saint-Croix-sur-Mer.

Smith was listed as missing presumed killed. The squadron leader wrote to Smith’s father “The loss of Lacy has deprived the Squadron of a pilot whose skill, courage and cheerfulness were an example to all of us…”. Recently married to an English lass, his young wife June received a similar letter.

The wreck of his aircraft remained missing for over 66 years. When finally discovered Smith was interred in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery at Ranville. The inscription on his headstone reads: “Oh I have slipped the surly bonds of earth and danced the skies on laughter’s silvered wings.”

Another fighter pilot from Sydney with an English sweetheart was Ronald Samm Adcock. Adcock was posted to a British squadron, No.3 Squadron RAF. At the commencement of Operation OVERLORD, he flew fighter cover for the armada heading for Normandy. From 11 June his squadron was redeployed on Operation DIVER. He flew one, two, occasionally three sorties in a day attacking launch sites of Hitler’s vengeance weapons – the V-1 flying bomb. An audacious aviator Adcock was one of the first to discover that if he flew beside a V-1 and flipped it with his wingtip the weapon would crash. It must have taken extraordinary courage and flying skill to pull off such a manoeuvre.

Adcock survived OVERLORD and DIVER but was shot down in flames in 1945. He survived the crash but was captured and spent several weeks a prisoner before being liberated. He rushed back to Britain and married his Betty. Evidence of his burns are still slightly visible in his wedding photograph.

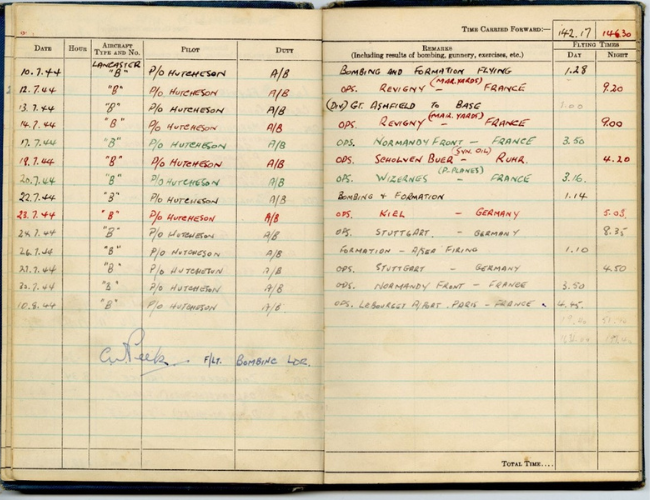

Today Adcock’s uniform, medals and flying log are on display in the permanent gallery at the Anzac Memorial.

Twenty-six-year-old South Australian Pilot Officer Clem Lea, navigator in an RAF B-25 bomber, marked his flying log, in underlined red block capitals, “OPS [Operations] D-DAY ATTACK RAILWAY ROAD BRIDGE 17m S.W. CAEN NR. ST. REMY / LIGHT FLAK” after surviving a low-level attack on the German transport hub at 2:50 on the morning of the landing! Clem survived the war and, like Adcock and many others, brought his English war bride back to Australia. Their son is the Collection Manager at the Anzac Memorial.

Another Mitchell crewman with the Allied 2nd Tactical Airforce supporting OVERLORD was wireless operator/air gunner Flight Sergeant Donald Ahearn from Kingsford in Sydney. Ahearn enlisted the week before his 21st birthday. He was listed as missing in action the week before his 23rd. In just over a month with his squadron Ahearn had flown over 21 missions. His bomber was hit returning from its 22nd strike on the night of 18 June. A year after D-Day Ahearn’s parents were still asking for information. Eventually the crash site was found. The family could have his headstone inscribed:

“In Honor’s Call

He Gave His All

And Man Can Do No More”

Also relocated from their crash site to the Commonwealth cemetery at Bayeux, their headstones side-by-side with the rest of their British crew, lie 28-year-old Queensland born Lancaster bomber skipper Pilot Officer Roland Ward, who enlisted from Coogee, and his gunner Flight Sergeant Malcolm Burgess from the Sydney suburb of Vaucluse. Flying with No.50 (Lancaster) Squadron RAF they were shot down bombing the German battery at St-Pierre-du-Mont in the early hours of 6 June. It was three days before Burgess’s 22nd birthday.

The most unexpected last fight by another Australian flying in an RAF squadron, in his case No.106 (Lancaster) Squadron, was the story of bomb aimer, Flight Sergeant Stanley Black, a 21-year-old from North Fitzroy.

The Lancaster Black and his crewmates were flying in was hit by flak over Caen on a bombing mission on the night of 6/7 June. Black and one other jumped clear. The rest of the crew died in the crash.

Separated from his mate in the dark, after wandering the French countryside, Black joined a lost company of US paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division. Deep in enemy territory they found themselves in the path of elements from the 17th SS Panzer Grenadiers making their way to the battle on the coast. Outnumbered and surrounded, the paratroopers, Black and a few French villagers fought until their ammunition ran out. Some paratroopers escaped. Black and the others were killed. His body was relocated to Bayeux in 1947 but he is also listed on the memorial in the France village of Graignes where he and a handful of Americans defended it to the last.

In a nearby plot at Bayeux lies another 21-year-old, Pilot Officer Frederick Knight from Haberfield in Sydney. Knight had been trying to enlist in the RAAF since the outbreak of the war but was rejected due to his youth. He finally received his wings at the age of 20 in March 1943. In early May 1944 he was posted to the ‘all-Australian’ No.460 (Lancaster) Squadron, a unit with an impressive record and a big reputation. On D-Day the squadron flew an operation in the morning and in the evening were tasked to fly again, this time to destroy the road and rail junction at Vire south of Caen, to prevent German reinforcements reaching the bridgehead. Such a precision target was not easy for heavy bombers.

Knight’s Lancaster was hit by flak shortly after crossing the French coast. The other 23 aircraft from the squadron bombed the target and returned to their base at Binbrook. Knight and his crew were posted missing. It took days before the report that his aircraft had crashed in flames was received. His date of death is recorded as 7 June 1944. Knight’s parents had inscribed on his headstone:

“He gave his tomorrows

For our todays.

Our only beloved son.”

Knight, Ahearn, Black, Ward, Burgess and the others were some of the 28,000 British and Dominion aircrew lost on operations connected to OVERLORD.

Remembering 1944 in Normandy

As a historian with a passion for cultural tourism I find Normandy fascinating because of its obsession with 1944.

One has to look hard for any explanations of the Bronze Age history of Normandy or of Roman occupation, or raids by Vikings. Even the origins of the legendary William the Conqueror, and the events of 1066, or Joan of Arc, being burned at the stake in Rouen, have to compete with statues of 1944 personalities, from General Eisenhower to US paratrooper Lieutenant Dick Winters, or the questionable story of the airborne rifleman John Steele hanging from the church roof at Sainte-Mere-Eglise.

Bayeux may have the famous tapestry but there are at least 30 public and private museums to Operation OVERLORD.

As well as the museums there are dozens of memorials to the events of 1944 in Normandy from the heritage park at Pointe du Hoc to the statue erected in Sainte-Marie-du-Mont to remember the 800 Danish seamen who ferried the US troops ashore.

Possibly the most visited site is the huge US cemetery at Colleville, lines of survey-placed white crosses and stars of David, 9,386 of them, marking the graves of US personnel lost during the campaign. The cemetery was completed in 1956. It stretches over 70 hectares above Omaha Beach.

Inland and west of the US cemetery is the large German cemetery at La Cambre. Containing over 21,200 bodies, it and the other German cemeteries, collectively hold over 66,000 graves. They were built in the 1950s and early 60s by the Volksbund, a private society for the care of German war graves.

The British equivalent is the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery at Bayeux with its 4,258 headstones, 17 of them commemorate members of the RAAF and RAN. It was completed in 1952. There are 15 other British and two Canadian cemeteries in Normandy as well as isolated war graves in local churchyards.

D-Day historiography

While the smashed towns were being rebuilt, the dead exhumed and reburied, and locals returning, veterans and official historians got busy at their typewriters. One of the first and finest accounts were the chapters in The Struggle for Europe written by Australian journalist Chester Wilmot and published in 1952. Wilmot had seen action in almost every theatre of the war. Originally attached to Australian forces he had his accreditation revoked by the corpulent, bumbling Australian General Thomas Blamey after criticising the incompetent commander. Snapped up by the BBC, Wilmot had been part of D-Day as he landed by glider east of the Orne River near Pegasus Bridge with a unit of the British 6th Airborne Division during the night of 5/6 June.

In 1959 Irish-born US journalist Cornelius Ryan completed his grand historical narrative The Longest Day. Ryan had been embedded with George Patton's 3rd US Army during the Normandy campaign. In 1963 20th Century Fox turned his book into the monumental film with the same title using 48 international movie stars. It was one of the great war movies of its time. The Longest Day preserved many of the myths of D-Day however it did present a surprisingly even representation of both Allied and Axis perspectives. The BBC followed suit a decade later with its extensive and detailed 26-part series The World at War in which veterans of D-Day, from both sides, were interviewed.

Pilgrimages to the Normandy beaches did not let up through the 1970s, ‘80s and early ‘90s. There was a steady flow to visit the cemeteries and the battlefields. Local collectors created displays that might attract a few tourist dollars but in the late 1990s there was a sudden burst of interest and a reappraisal by historians.

The US film industry surfed the wave of renewed interest. In 1998 Hanks and Spielberg created the indelible impression of D-Day we discussed earlier. They built on that in 2001 with the extremely popular miniseries Band of Brothers.

British Army officer turned historian Antony Beevor wrote D-Day; The battle for Normandy timed for release with the 65th anniversary.

By the time the 70th anniversary came along in 2014 the obvious public interest inspired an event attended by the handful of surviving veterans and the world leaders of nations that had been involved in the Second World War. They gathered on Sword Beach for the ceremony.

That anniversary was recently recalled in the British film The Great Escaper, (2023) starring Michael Caine and Glenda Jackson. It depicted the journey by D-Day veteran Bernie Jordan who left his retirement home to make a personal pilgrimage without informing his carers.

Modern memorials to D-Day

Five years ago, a very powerful sculpture was added to the lexicon of memorials in the British sector of the Normandy beaches. On the cliff above Arromanches, where the remains of the Mulberry Harbor can still be seen off-shore, is the D-Day 75 Garden – Le Jardin du Souvenir. Its symbolism includes a carving of 97-year-old veteran Bill Pendell and the ghostly forms, of British troops wading ashore through the surf, made from wire mesh.

Ten minutes down the road from Arromanches, on the ridge above Gold Beach, now stands the British Normandy Memorial. Incomplete by the time of the 75th anniversary it was unveiled on 6 June 2021.

It is a grand memorial that combines convention and artistry. The memorial occupies a bare ridgeline that overlooks the British landing beach. At the heart of the memorial is a bronze of three British troops running forward. They are mounted on a pale concrete plinth. The plinth stands in the centre of a paved area surrounded on three sides by concrete walls. The walls are open to a view of the slope down to the beach and out over the Channel. Radiating from the walls are roofed pavilions that follow the ridgeline to the east and west. The columns holding up the roof are engraved with the dates of the campaign. Each day is accompanied by an honour roll of those who died that day. The memorial lists 22,442 names.

For me the memorial solves a problem in that, until it was built, many of those who died on Operation OVERLORD, and have no known grave, are not remembered in France. The Royal Navy’s dead for example are listed on the naval memorial in Plymouth. Among those names is the Australian sailor, Sub-Lieutenant Richard ‘Digger’ Pirrie. The British Normandy Memorial has ensured that Digger Pirrie is commemorated in France.

On 6 June 2024 an extension to The British Normandy Memorial was unveiled. I have seen few extensions to memorials that appear seamless, appropriate or have worked aesthetically. This is an exception!

The extension consists of 1,475 black metal silhouettes. They are silhouettes, slightly larger than life size, of British and dominion sailors, soldiers and airmen. They are stationary but appearing to walk, with head bowed, through the ankle high scrub between the memorial and the coastal path above the beach. The 1,475 figures represent each of the men killed at the landing. I cannot explain why but they work. One cannot help but feel drawn to those inanimate but somehow compelling forms that express in mute eloquence the tragic loss of young lives.

Memorials are an artistic statement made to evoke contemplation. They may not add to our knowledge of the history of the event however if those memorials, inspire visitors to think about and to reflect on the courage and self-sacrifice, of bonds of comradeship, of the generation who fought and died on those beaches, their story will live on.

D-Day, and the campaign that followed, was an event that will live forever in recorded history. Today there are few left who served on that day of days. The battle has moved from memory to history.

The Slouch Hat on D-Day

Say D-Day and the immediate image is not of bombers targeting railway yards from altitude or sailors battling a storm-swept English Channel but of men wading ashore and charging across open beaches, from wooden landing craft, in the face of withering machine gun fire. The only member of the AIF to have an experience that comes close was Major H B ‘Jo’ Gullett MC.

Gullett, a 29-year-old Sorbonne and Oxford educated journalist had enlisted in the Victorian raised, 2/6 Battalion as a Private in 1939. An NCO in North Africa he was wounded in the attack on Bardia in January 1941. Commissioned when he recovered, he commanded a platoon during the disastrous Greek campaign in April. In 1942 and ’43 he fought in Papua and New Guinea, earning a Military Cross in the desperate defence of Wau. In 1944 he volunteered to join Australian army observers of Operation OVERLORD. Ever the man of action, Jo renounced his observer status, despite official opposition, so that he could join a British regiment earmarked for the landing. He was posted to a battalion the Green Howards as a deputy company commander.

Disappointed that he was not allowed to wear his AIF uniform for the occasion, on the grounds that AIF service dress looked too similar to the German field uniform, he strapped his slouch hat to his pack, made sure that his British battle dress sported Rising Sun collar badges and the weapon he carried was his trusty SMLE No.1 Mk.III* rather than the No.4 rifle, of the same calibre, carried by British troops.

Operation OVERLORD inspired Jo’s warrior spirit. On the Kokoda Trail in ’42 and the New Guinea jungle in ’43 he had fought the enemy in relatively small unit actions, often in almost hand to hand combat. Even the North African and Greek battles he had seen action in, back in 1941, were nothing like D-Day. During the Channel crossing he was awed by the view, from his vessel, of an armada of ships, of all shapes and sizes and packed with hundreds of thousands of soldiers and sailors, that seemed to stretch to the horizon, while above, the very air throbbed with the vibration of the aeroengines of bombers, fighters and transports towing gliders that filled the sky, all headed for a hostile shore that bristled with enemy guns.

He had never seen anything of this magnitude before and felt he was watching a world at war. Describing it to me 50 years later I could still see the excitement in his eyes as he relived the scene.

Jo landed at King Sector of Gold Beach. He was witness to the courage of Company Sergeant Major Stan Hollis, the only soldier to earn the Victoria Cross that day. Once off the beach Jo led his men in the capture of an enemy bunker between Ver-sur-Mer and Crépon. He was wounded for the third time in his military service a few weeks later.

One of Jo’s most treasured memories of D-Day was a letter he received from fellow Melbourne Herald journalist Alan Moorehead. Moorehead had served as a journalist through the North African and Italian campaigns and had been twice mentioned in despatches. He would eventually be appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (Military).

On D-Day he landed on Gold Beach and passed his former colleague from civilian days, Jo Gullett, heading inland with his unit. After the war he wrote to Jo saying: “I hope you will always be as happy as you looked riding on that tank on D-Day.”

The legacy of D-Day

D-Day and the campaign that followed was an event that will live forever in recorded history. Those who were there all played a role, great or small.

That war is a human tragedy there is no doubt but for many veterans their experiences include recollections of courage and self-sacrifice, of bonds of comradeship that they valued for the rest of their lives.

With another dictator fighting an aggressive war in Europe it is timely to reflect on the war 80 years ago and that longest of days, a battle that changed European history.

Let us commemorate the men who died in Normandy. Remember that they fought for what they believed in and for their mates, and remember the grief suffered by those who loved them.

We have a duty to ensure that the echoes of that time do not fade for they hold lessons of value for us to this day and into the future.

Lecture by:

Brad Manera

Senior Historian / Curator

Anzac Memorial

6 June 2024