Photo: Don Heussler Collection, Anzac Memorial Collection.

The Anzac Memorial was recently gifted a remarkable set of three rare silky oak frames containing an extraordinary collection of mostly military badges. The badges, mounted on plush velvet hand-stitched backgrounds were collected by Sydneysider Oswald Walter Moore in the years leading up to the Great War. The largest of the frames is well over a metre high and contains British infantry regiment and army corps badges with a mix of Queen Victoria and Kings Crowns. A smaller frame is of British cavalry regiments and the third, and perhaps most significant, is of NSW militia units with the occasional trade badge, corps badge and skill-at-arms badge randomly positioned within.

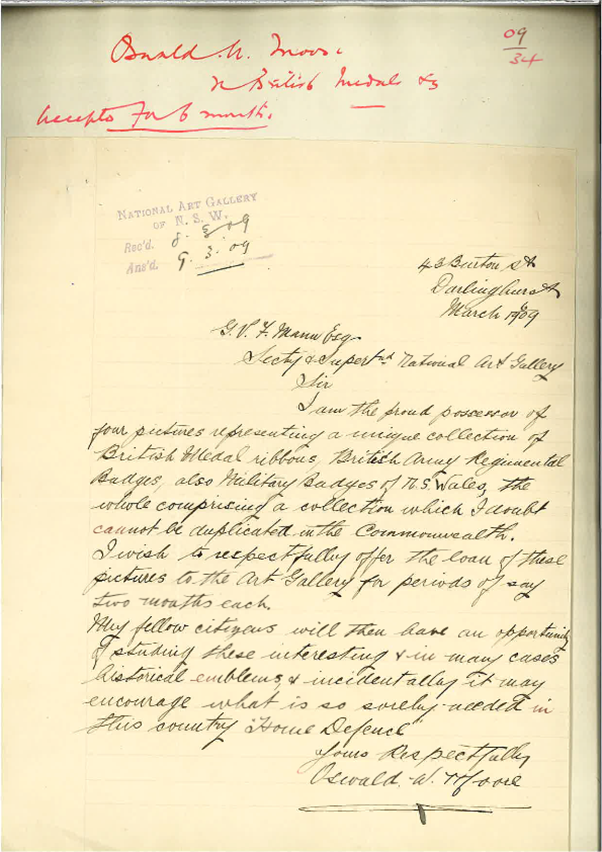

Whilst collections such as these were popularly curated and often displayed at private soirees and exhibited in public galleries in the early years of the twentieth century, today they are very scarce indeed. The collection originally comprised four frames; the fourth was a set of British campaign ribbons. We know this because our Research Exhibitions Officer Dr Catie Gilchrist has unearthed correspondence between Oswald Moore and the National Art Gallery (today the Art Gallery of NSW) when he loaned his collection to a public exhibition held there in 1909. Moore was very pleased with his collection and he wished for the public to share in his delight. In a letter to the art gallery dated 6 March 1909 he wrote:

I am the proud possessor of four pictures representing a unique collection of British medal ribbons, British Army Regimental Badges, also Military Badges of N. S. Wales, the whole comprising a collection which I doubt cannot be duplicated in the Commonwealth.

I wish to respectfully offer the loan of these pictures to the Art Gallery for periods of say two months each.

My fellow citizens will then have an opportunity of studying these interesting and in many cases historical emblems and incidentally it may encourage what is so sorely needed in this country “Home Defence”.

Rather tragically, the whereabouts of the fourth frame is today unknown.

Photo: Letter Courtesy of the Art Gallery of NSW.

Oswald Walter Moore

Oswald Walter Moore was born in Dunedin, New Zealand in April 1881. His parents were English-born Richard James John Moore (1855-1918) and Sarah Lydia Moore nee Sturgeon (1853-1938) who married in Dunedin in 1876. The Moores also had two daughters. Mable Beatrice Moore was born in 1883 and Dorothy Sudbourne Moore was born in 1891. The family moved to Sydney, and in the 1900s Oswald Moore was living at 43 Burton Street in Darlinghurst. By 1913 however the entire family were listed on the electoral roll at ‘East Anglia’, 220 Maroubra Bay Road, South Randwick.

Oswald was employed as a cutter at Evans and Cohen’s tailoring emporium on Wynyard Street. Since 1884 the company had specialised in manufacturing work and military uniforms. Both Mable and Dorothy were occupationally described on the electoral roll as ‘embroidress’. It is highly possible that one or both of them contributed the beautiful velvet backgrounds to the frames and to the bullion work of the elaborate embroidered oval-shaped label in the middle of the colonial badge frame.

Moore’s War

With his penchant for collecting military badges and his work with a company making military uniforms, it is perhaps not surprising that by the outbreak of the Great War, Moore already had over fifteen years’ experience as a military forces volunteer; he was a senior NCO with the 21st Infantry, Sydney Battalion (Woollahra). And his patriotism and his great passion for all things martial was confirmed when he became one of the first to enlist with the AIF during the early days of recruiting. On 22 August 1914 the 33-year-old bachelor enlisted in Sydney and was given the service number 324. The AIF promoted him to the rank of Sergeant (the senior NCO of an infantry platoon) in ‘C’ Company of the 1st Battalion. He embarked for overseas service on 18 October 1914 per HMAT Afric A19.

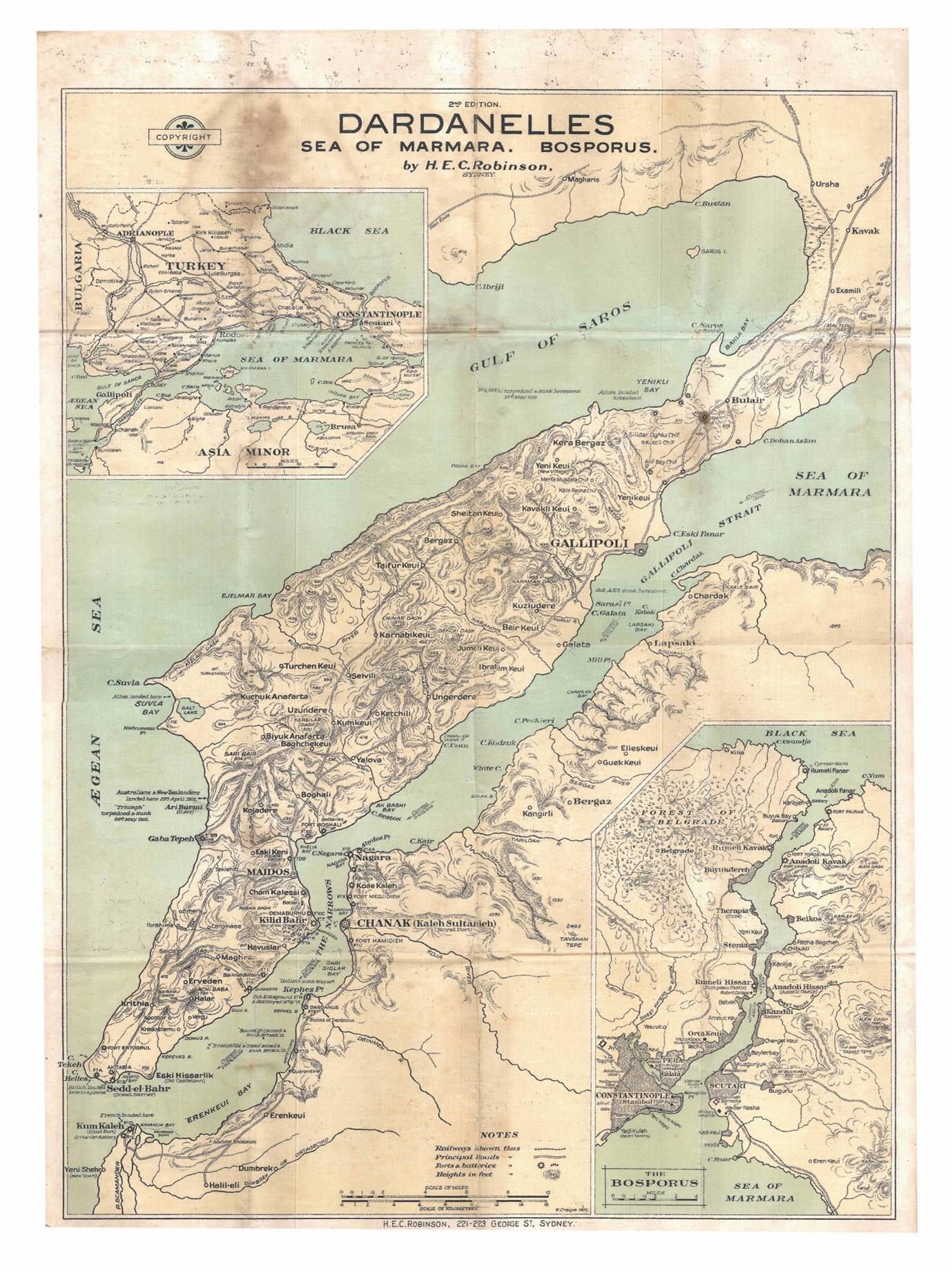

Image: This map of the Dardanelles was widely distributed in NSW during the war. It shows the initial landing site at Ari Burnu and the British and French landing site around Cape Helles. Anzac Memorial Collection.

Sergeant Moore landed at Gallipoli with his battalion on the morning of 25 April 1915. By 30 April 1915, 860 Australians had died at Gallipoli, most from wounds received in the running battles in the ridges and gullies during those first chaotic days of the campaign. A few died from disease. May 1915 would see the loss of over 2,000 more.[1] The disastrous attack on Baby 700 on the night of 2-3 May cost 1,000 casualties, half of them killed ‘and left to rot on Dead Man’s Ridge’.[2] During the battle, Oswald Moore was wounded and he was removed from the peninsula to recover in hospital on the Mediterranean island of Malta. He subsequently rejoined his battalion on 18 May but just days later a sniper shot him through the head whilst he was looking over a reserve trench parapet at Courtney’s Post.[3] Turkish snipers were an ever-present danger to Anzac troops at Gallipoli largely because they held the advantageous high ground which afforded them clear sight of the enemy below; by late May 1915 they had been practising their deadly art for weeks and no man, private or general, was safe.[4] According to Les Carlyon, ‘they knew the thoroughfares and routines of Anzac, particularly along Shrapnel Gully and Monash Valley, which they overlooked from Baby 700 and Dead Man’s Ridge. With the sun behind them they sometimes hit 20 men in a morning.’[5] Moore’s mates swiftly carried him down to the New Zealand and Australian Clearing Station but he died of ‘wounds received in action’ later that day.

A Temporary Armistice

‘…the dead and wounded lay everywhere in hundreds. Many of those nearest to the Anzac line had been shattered by the terrible wounds inflicted by modern bullets at short ranges. No sound came from that dreadful space…’[6]

Photo: Dead Turks lying in gravelly gutter on the Nek. They were killed on 19 May 1915. This photograph was taken on armistice day, 24 May 1915. AWM G01440A.

Moore’s death on 24 May 1915 was particularly tragic because a formal temporary armistice came into effect that very day.[7] Quite simply, the decomposing bodies of the thousands of dead who lay strewn across the terrain were threatening to become a serious health risk to both sides and they needed to be buried. In the hours between dawn and the beginning of the truce however, snipers remained active on both sides and this is probably when Moore was fatally wounded. Yet at 7.30am, white flags were indeed raised, whistles blew and the Anzacs and the Turks walked into no man’s land armed only with picks and shovels to bury thousands of fallen men; they were now black, rotting and swollen by the early summer heat, and had been cut down in the days and weeks before ‘like hay before the mower’.[8] According to the Official War Historian Charles Bean, ‘burial parties worked all day between the lines, each side interring the dead found in its own half of No-Man’s Land.’[9] Those found wounded and barely alive were also removed by the tireless efforts of teams of stretcher-bearers. It was a hot day, flies were swarming around the bloated corpses and the acrid stench was utterly nauseating. Dysentery was a clear and present danger. Yet throughout the nine-hour armistice the Anzacs and the Turks ‘exchanged souvenirs and when at 4.30 both sides returned to their trenches, parted as friends.’[10] Tragically the ceasefire did not last long; at 4.45pm a Turkish sniper opened fire.[11] Then the bombs and the bullets began again and normal service was resumed. Just after noon on the following day, Lieutenant Commander Otto Hersing in the German U-boat U-21 torpedoed HMS Triumph lying off Gaba Tepe. According to Charles Bean, ‘within fifteen minutes she turned bottom upwards and sank half an hour later under the eyes of both armies.’[12] Two days later HMS Majestic was similarly sunk at Helles by the same German U-boat.[13] After this all allied battleships were ordered to leave and relocate to the relative safety of ports at Imbros, Mudros and Alexandria; and so ‘the once great armada of warships that had thickened the waters off the peninsula disappeared.’[14] The withdrawal of the fleet greatly strengthened the flagging morale of the Turks; yet for the abandoned Anzacs left behind, the 24 of May had been a very temporary armistice indeed.

In Memorium

Moore’s personal effects which were eventually sent back to his family included a wallet, note book, cards, pipe and case, dictionary, camera, fountain pen, letters, whistle on a lanyard, wristlet watch and a gold ring. On 30 June 1921 his by now widowed mother signed for his Memorial Scroll and Kings Message and in November 1921 she received his Memorial Plaque. On both occasions she sent a handwritten letter to AIF Base Records Office in Melbourne, to acknowledge her deep gratitude. She did the same again in July 1922 when her son’s war medals were issued to acknowledge his service and sacrifice. Today, 324 Sergeant Oswald Walter Moore is commemorated at the Lone Pine Memorial 13 in Turkey.

Photo: Courtesy of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website.

A Family Heirloom

Before he embarked from Sydney in October 1914 Moore had left his will in the private safe at his family home. Probate was granted in September 1915 but what was the fate of his badge collection? His father died in 1918 and his sister Mable never married and died childless on 2 August 1943. Oswald’s other sister Dorothy married Frank Henry Cole in Newtown, Sydney in 1915. Cole had served with the AN&MEF in Rabaul between 11 August 1914 and 4 March 1915. On 14 August 1923 a son was born and with a respectful nod to his uncle killed at Gallipoli he was named Oswald Moore Cole. During the Second World War, Cole enlisted with the Australian Army just before his twentieth birthday on 7 June 1943. He served as a Trooper with 2 Tank Battalion until his discharge on 19 September 1946. Oswald Cole died on 6 September 1955, aged just 32 years. He was by then living at Peats Ridge and was working as an orchardist.

After the Great War Frank Cole had applied for a soldier settlement and in 1936 Dorothy and Frank were living on Farm 1235, Corbie Hill, Leeton in the Riverina District of southern NSW. There is no divorce record however by 1949 Dorothy was living back at the Moore family home in Maroubra, without Frank. She remained there until her death in June 1956. Frank Henry Cole died on 7 August 1972, aged 83 years and was buried in the same grave as his son in the Methodist section of Point Clare Cemetery, Gosford, NSW.

The Donor

Moore’s magnificent military badge collection was donated to the Anzac Memorial in 2021 by Don Heussler. According to Mr. Heussler, Frank and Dorothy Cole also had a daughter, Sybil Cremer Cole (later Wiles) (1918–2004). The electoral roll for 1958 shows that Oswald’s niece Sybil Wiles was living at the Moore family home at 220 Maroubra Bay Road. Presumably, as the last surviving child, she inherited the house and its contents after her mother’s death in 1938. This is confirmed by Don’s story. Her husband was Reginald Ignatius Wiles (1916-1977) and they had a son called Reynold Martin Wiles who was the donor’s school chum. Don recalls the imposing presence in the house of Oswald Moore’s badge collection, some forty years after his death at Gallipoli. The Wiles emigrated to New Guinea in 1960, and, fearful that the climate would damage Sybil’s uncle’s collection, they gave it to Don Heussler for safekeeping.[15] Today that safekeeping of such a rare and extraordinary artefact continues at the Anzac Memorial.

The Collection

Pre-Federation Military badges

This collection of badges is framed in NSW silky oak and measures 84cm x 63cm. The badges are mounted on red velvet and have a wide gilt frame mount; the central oval piece in raised bullion states “Military Badges of NSW”. There are 48 metal badges, 9 buttons and 4 cloth badges for a total of 61 insignia. All relate to military service in colonial NSW prior to Federation in 1901. It is a very rare collection indeed.

Infantry badges of the British Army

This collection of badges is framed in NSW silky oak, measures 72cm x 126cm and is mounted on burgundy velvet. The badges were framed by Styles and Co of Rowe Street, Sydney. There are 102 in total. Each badge is named and numbered by an individual label. On the back of the frame is a loan card stating that the item was loaned to the National Art Gallery of NSW by Oswald W Moore Esq.

Cavalry Badges of the British Army

This collection of badges is framed in NSW silky oak, measures 57cm x 68cm and is mounted on black velvet. There are 40 badges in total in this frame which have been numbered for reference.

Notes

- https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/gallipoli/fatalities

- A. K. Macdougall, Australians at War; A Pictorial History, The Five Mile Press, Victoria, 2002, p 55.

- Courtney's Post was the centre post of three - Quinn's, Courtney's and Steele's that occupied precarious, but critical positions along the lip of Monash Valley, in the heights above Anzac Cove. The post was named after Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Courtney, commander of the 14th Battalion, which had occupied the position on 27 April 1915.

- On 15 May 1915 Major-General William Throsby Bridges was mortally wounded by a Turkish sniper and died three days later; his was the only body to be taken home from Gallipoli. Today his remains lie on a hillside at Duntroon, Canberra at the military college he founded.

- Les Carlyon, Gallipoli, Pan Macmillan Australia, Sydney, 2002, p 264.

- Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 2, The Story of Anzac from 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, 11th edition, 1941, p 161.

- By sunrise on 20 May 1915 almost 10,000 Turks had been gunned down of which over 3,300 had been killed and 486 were missing in action. In contrast the Allies lost 160 dead and 468 wounded. Harvey Broadbent, Defending Gallipoli, The Turkish Story, Melbourne University Press, 2015, pp 142-43.

- By sunrise on 20 May 1915 almost 10,000 Turks had been gunned down of which over 3,300 had been killed and 486 were missing in action. In contrast the Allies lost 160 dead and 468 wounded. Harvey Broadbent, Defending Gallipoli, The Turkish Story, Melbourne University Press, 2015, pp 142-43.

- Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 2, The Story of Anzac from 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, 11th edition, 1941, p 167.

- Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 2, The Story of Anzac from 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, 11th edition, 1941, pp 167-68.

- Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 2, The Story of Anzac from 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, 11th edition, 1941, p 168.

- Remarkably almost the entire crew were saved. Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol 2, The Story of Anzac from 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, 11th edition, 1941, p 170.

- For these two actions Hersing was awarded the Pour le Merite, Germany’s highest military medal awarded during the Great War.

- A. K. Macdougall, Australians at War; A Pictorial History, The Five Mile Press, Victoria, 2002, p 59.

- By 1977 the Wiles had returned to live in Queensland which is where Reginald was buried after his death on 22 September 1977.