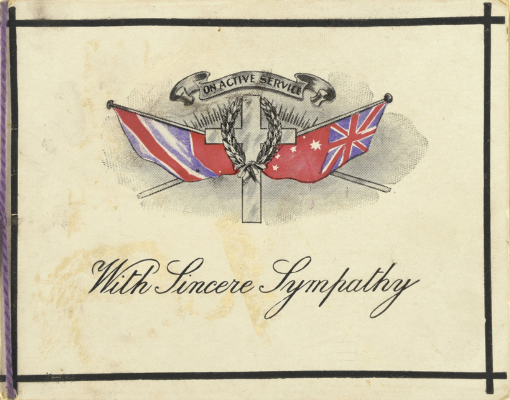

The horrific casualty rates during the Great War generated unprecedented national grief as tens of thousands of Australian households received fateful letters and telegrams regretfully telling them that a soldier son, husband, father or brother would never be coming home. Every home with a family member in the Australian Imperial Force lived with the dread of receiving the fateful news from the other side of the world, an anxiety that could only be removed by the safe return of their soldier folk.

Yet there were other circumstances inflicting grief, for while the war vastly increased the death rate among young Australian men, death itself did not relent on taking its usual toll among the civilian population at home. Some soldiers, while serving overseas, received dreadful news of the loss of a loved one, a strange reversal of expectations that often caught the soldier by surprise. Death at the front was commonplace, but they were less equipped to manage sad news from home. One soldier recorded being heartsore after receiving news of his mother’s death while he served at Gallipoli. Sitting through a church service on the sheltered side of a hill on 6 June 1915, the day after hearing receiving the fateful letter, he reflected in his diary, ‘I went with a very sad heart; as the Minister preached, I did not hear much, but in some strange and wonderful way God spoke to me.’ [1]

Another soldier, Neville Davies, an electrical mechanic from Newcastle employed at the Cockle Creek Sulphide works, was engaged to Edna ‘Eddie’ Mathews, a girl in his local Baptist church. Davies had been rejected as medically unfit in August 1915 because of a recent hernia operation, but enlisted as a Private in January 1916, aged 22, becoming a Lance Corporal and eventually realizing his ambition of an officer’s commission in September 1917, and commanding the Machine Gun Section of the 35th Battalion with great skill.

During his time overseas, he wrote to his fiancée regularly. Many of his letters to Eddie from the ship voyage to Europe, from camps in Britain, and in the war zone in France repeated his eager desire to be home and get married. In July 1916, he wrote, ‘Being separated from you is beginning to tell, and I wish with all my heart that the War was over, and that I could come back to you.’

Hearing the singing in a church service near his camp in England, he was struck with nostalgia. He was saddened by the closing hymn for absent loved ones. ‘Oh, dearie,’ he sighed, ‘if you only knew how often I long to see you and be near you.’

Once, he and a friend were accosted by two young ladies who tried to latch on to them, but Davies brushed them away. ‘Fancy what a temptation this would be for a youngster fresh from home,’ he wrote. ‘I am thankful I have a strong will, and could resist such a thing, but it fairly made me blush with shame to see such a young girl down so low, morally.’

Davies served in France for a time, and was offered the chance of a commission, though it took several months for this to become a reality. By June 1917, he had been pulled out of the Battle of Messines and sent to Oxford for officer training. Having survived heavy shelling, he wrote in anguish, ‘Oh, Eddie, Dear, you cannot imagine how often I have looked death right in the eyes, and even been certain that I would be killed, and I have thought of my dearest one, and wondered what would become of her, and how the news would be broken and all that.’ In England for officer training, he developed the conviction that having survived so many potentially fatal encounters, he would now be spared, though he was realistic enough to think through the consequences to Eddie if he was killed.

By July 1917, his letters were filled with the anticipation of coming home, insisting that they would marry within a day or two of him landing. ‘How I long for you always, my own, and constantly pray that God will keep my beloved safe and soon unite us together again as man and wife,’ he wrote, adding in the next letter, ‘What a time we will have, darling, when this is all over, and if God wills that I shall come home back to you safely.’ As his training drew to a close in September 1917, he dreaded the coming winter in France.

Eddie was not his only correspondent. Her 11-year-old sister Esma (Doll) wrote him a number of letters full of spirited sarcasm and wit. Davies shared the sister’s banter in his letters to Eddie, laughing at the cheek of Doll, who teased him about his relationship with Eddie.

In late October 1917, he rejoined his Battalion as an officer. The winter months in France were quiet, but on leave in England in February, he told Eddie that he would be in battle on his return and warned her to be prepared if he was killed or wounded. While he felt sure of divine protection, he added, ‘yet his will may be otherwise, and I am not afraid to go, girlie. It almost breaks my heart, though, to think of you being left, and so far away, and I know, after experience of the Passchendaele battle how meagre the news is, that you will get, in case I get either missing or killed.’ He was pleased to receive further training in March, as it took him away from the dangers of the German offensive, and into comfortable circumstances. However, as the newly appointed Battalion Machine Gun commander, a role he particularly enjoyed, he was at the front for the rest of the war and experienced a sequence of near misses.

The long separation took its toll on their relationship, and writing on 1 March 1918, he wondered at the changes both of them must surely have been through while apart. Davies stepped up conversations about marriage, discussing finances and arrangements for setting up home, sending her presents of clothes he had bought her, and again reinforcing his restlessness to be home, and married quickly, but ending with appeals to patience. Their relationship had been tested by war, with each experiencing worries over misunderstandings in letters, and fears of the end of the relationship when no mail had arrived for weeks at a time. However, their bond was strong. He told her in July of being teased by companions who ‘say to me, “oh, she is knocking about with somebody else, by this,” but, I know my sweetheart too well, and laugh at their ideas’.

Davies was heavily engaged in the battles of August through to October 1918, where the Australians pushed back the Germans, but suffered heavy casualties as well. When the war ended on 11 November 1918, Davies became particularly impatient to return, but had to wait until May 1919 to leave. His ship stopped over in Melbourne in June, where he received a fateful letter from Eddie’s father telling of Eddie’s sudden passing from the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919. Having survived countless dangers himself, the tragic irony of his fiancée’s death just as he arrived home for his much-anticipated wedding was a shattering blow. However, Davies worked through his grief, and maintained his connection to the Mathews family, courting Esma several years later and marrying her in July 1924. [2]

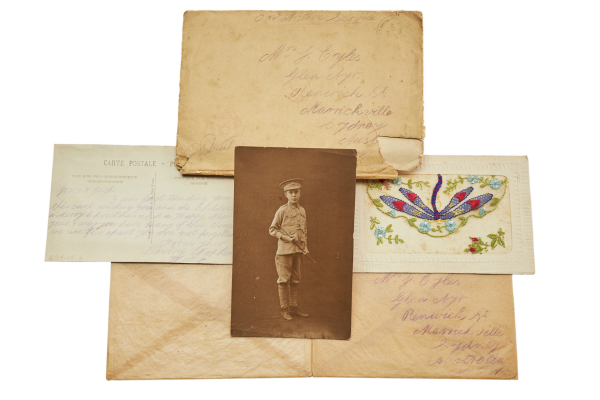

But even more tragic is the story of Walter Eyles, a Sydney-born, 17-year-old horse driver who put his age up to 21 in order to enlist without parental permission. His diaries and a number of family papers are held in the Anzac Memorial Collection. His parents had separated before the war, but the situation was filled with ongoing tensions over his father William’s periodic domestic violence and an affair with their former maid. He was irregular in paying maintenance to his estranged wife Ellen, who struggled to make do while supporting two school aged daughters. [3] Another son appears to have not been in a position to help. [4]

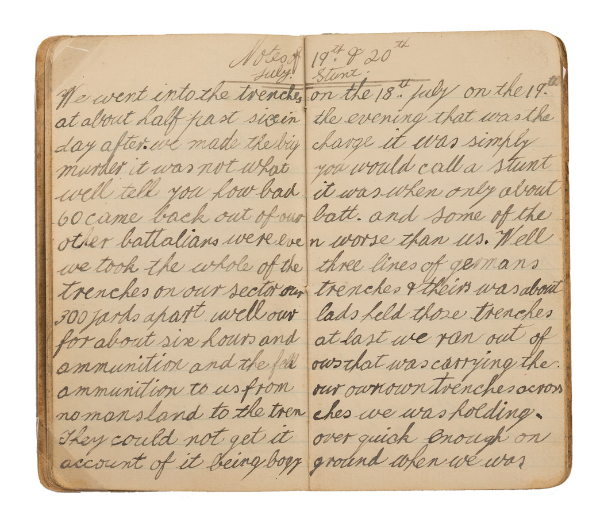

Eyles enlisted in October 1915, and sailed for Egypt in late December with the 13th Reinforcements for the 2nd Battalion. However, he was allocated to the 54th Battalion in February 1916, when the Australian 1st Division battalions were split to provide personnel for the newly created 5th Division. In June, the 5th Division went to France and a month later was thrown into the furnace of the Battle of Fromelles, where 65% of the battalion became casualties. One historian has described the battle as ‘the worst 24 hours in Australia’s entire history’. [5] Eyles’ role in the battle was as an ammunition carrier supporting the attack. He was forced to shelter for periods of time in shell holes to avoid the murderous machine gun fire, which at one point literally shot the pocket off his coat. It contained two grenades – if either had been hit, the explosion would almost certainly have killed him. [6] He was one of the fortunate ones to escape injury, let alone death.

For the rest of the year, the battalion held the line at various places, finally enduring Europe’s coldest winter in 40 years. Moving to the Somme late in the year, he spent a week in the trenches from 26-30 October that he described in his characteristically uneducated English as ‘the roughest time ever I had in all my life well no one could realise what we are going through unless they saw it for themselves the sooner we get out of this place the better it his marvelious to me that their his any of us left my mates are getting mowed down all around me at this present hour’. [7] Given the traumas of Fromelles, this is some statement.

However, during those days on the Somme, a tragedy unfolded at home which affected him even more deeply. His father William was arrested for failing on his maintenance payments. On 13 October 1916, he went to his old home, apparently searching for papers that held evidence against him. Neighbours saw him leaving, clutching a folio of documents. Hours later, his wife Ellen was found hanging from the bedpost by her 11-year-old daughter Alice, who came home early after a school excursion that day. The horrific discovery was compounded by evidence of violence, the mother’s face being battered, and bloodstains left on the bed and curtains. [8] Her husband was quickly identified as the prime suspect, though he protested his innocence over the course of a prolonged process of justice. His defence was built around assertions that he had not been near his wife for several years, that his wife had shown suicidal tendencies for some time, and that he was a respected member of the community, a carpenter and plumber by trade and a city councillor and former mayor of Drummoyne. The murder and the subsequent enquiry and legal proceedings was sensational news that was widely reported around Australia.

William was found guilty of murder in December 1916 after a mere 30 minutes’ deliberation by the jury and sentenced to hang. Witnesses testified that he had been seen at his wife’s home on the day of her death, his daughter Alice remembering that he had tried to choke his wife on an earlier occasion, and his eldest son Arthur denying that he had ever heard his mother speak of suicide. [9]

As tragic as all this was, it got even messier. He appealed his conviction on the grounds of circumstantial evidence and the apparent bias of the judge, based on comments made during the trial. His conviction was quashed, and a retrial ordered, but he was almost immediately charged with perjury for claiming he was not at the house that day. He was reconvicted in June, and his appeal was denied in July. However, his death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. [10]

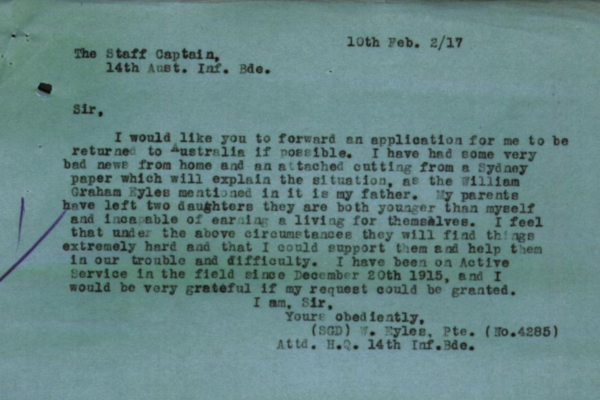

As the extended trial played out, the four children had to cope with the loss of one parent, the likely execution of the other, and the removal of their only means of support. Exactly when the news was conveyed to Walter is unknown. He was hospitalised with bronchitis in November 1916, returning to his unit in early February. His diary betrays no knowledge of the tragedy before 10 February, when his army papers show that he applied for an immediate return to Australia, backed up by newspaper clippings from the December issue of the Sun, which he would have only just received by post.

He asked to return to Australia as soon as possible, as ‘I have had some very bad news from home and an attached cutting from a Sydney paper which will explain the situation, as the William Graham Eyles mentioned in it is my father. My parents have left two daughters they are both younger than myself and incapable of earning a living for themselves. I feel that under the above circumstances they will find things extremely hard and that I could support them and help them in our trouble and difficulty.’ [11]

Despite the dangers of war, Walter’s mind was clearly filled with the appalling situation at home. He had to cope with his own grief, but with his older brother apparently not able to help, he also felt a responsibility to his younger sisters, who had no means of support. At that distance, he could not even comfort them personally.

His army file contains the documents confirming the facts behind his request including a death notice from the Sun on 13 December 1916, ironically naming Ellen as the ‘beloved wife of William Eyles, age 43 years.’ Brigadier C. J. Hobkirk (though for some strange reason spelled ‘Hoopkirk’ in Eyles’ file), Officer Commanding the 14th Brigade in which the 54th Battalion served, signed off on the discharge, ‘as under the circumstances he rightly feels that his dependent sisters will have great difficulty in finding [sic] for themselves’. Eyles was described as ‘an excellent soldier and has done very good work at all times since his enlistment’. The paperwork filtered through the hands of AIF administrators, with one asking on 28 February if Eyles’ story could be independently corroborated by someone who knew him in civilian life. Sergeant Stanley Frost, who lived close to Eyles’ home in Five Dock, Sydney and who, being almost the same age was probably a friend, provided a confirming statement. ‘I knew his people very well and heard from my parents at home that his mother had been murdered. Pte. Eyles has two young sisters and the elder is about 13 years of age [another report suggests 16]. As far as I know Pte. Eyles has no relations upon whom the children could be dependent.’ [12]

After being released from hospital in February 1917, Eyles spent a month on leave and in retraining, and rejoined his battalion on 6 March, doubtless restless to hear of his application to return to Australia. Four days later, the II ANZAC Corps commander, Lieutenant General Alexander Godley, approved Eyles’ request. He received orders to begin his journey home on 20 March 1917, embarking on 1 May and arriving in Australia to an almost certainly melancholic welcome in June. From there, Eyles almost completely disappears from the records, but it can be assumed that he found work to support his sisters. The timing of his departure meant that he avoided yet another bloody battle, that of 2nd Bullecourt in May 1917, though his battalion was only involved in defensive actions.

On 13th December 1924 he married Vida Cunneen, and they had a daughter in December 1926. In the meantime, the family dramas continued, as his father attempted to escape from Goulburn jail in 1926 and was denied release in 1930. [13]

The experiences of Davies and Eyles illustrate the shock of sad news from home that added to the various traumas that soldiers experienced while serving at the front. Home represented a source of hope and optimism for many, so that calamity at home was often felt more deeply than the death of their friends in battle.

Notes

- William Cameron, Diary, 6 June 1915, 13 June, 1DRL 0185, Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

- Neville Ambrose Davies, A Triangle of Love: Neville Davies, Edna Mathews and Esma Mathews. MSS2048, Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

- National Australian Archives, B2455, Eyles W.

- ‘Five Dock Tragedy’, Evening News, 2 November 1916, p 8.

- Ross McMullin, (2006). ‘Disaster at Fromelles’. Wartime Magazine, Issue 36, Spring 2006, Canberra.

- Walter Eyles, diary, 19 and 20 July 1916. 2017.11, Anzac Memorial Collection.

- Walter Eyles, diary, 30 October 1916. 2017.11, Anzac Memorial Collection.

- ‘Supposed Murder’, Sydney Sunday Times, 15 October 1916, p 9.

- The Eyles Murder Appeal’, Daily Mercury, 23 December 1916, p 2; ‘Death of Ellen Eyles’, Northern Star, 3 November 1916, p 4; ‘Alleged Murder. William Eyles on Trial’, Northern Star, 14 December 1916, p 2.

- ‘General News’, Melbourne Age, 3 August 1917, p 8.

- National Australian Archives, B2455, Eyles W.

- National Australian Archives, B2455, Eyles W.

- ‘Attempted Escape’, Smith’s Weekly, 6 March 1926, p 3.