John Chauncy Champion de Crespigny was born in Melbourne on 25 August 1908. He was the fifth and youngest child of Philip and Barbara (Birdie) nee Walstab Champion de Crespigny. Philip was a successful journalist and with a large young family, his decision to enlist late in the Great War would not have been made lightly. [1] He enlisted on 26 November 1917 and embarked for the Middle East on 2 March 1918. Serving as No 3479, a Trooper with the 2nd Australian Light Horse Regiment, Philip de Crespigny was killed in action in Palestine on 14 July 1918. He is buried in the Commonwealth War Grave Cemetery just outside of Jerusalem. Today, his bronze Memorial Plaque is part of the Anzac Memorial’s collection. John was only nine years old when Philip died. How the loss of his father affected the young boy was probably deeply profound. Twenty-four years later, John had become a prisoner of the Imperial Japanese Army in Java, and despite his own dire circumstances, he remembered the anniversary of his father’s death in his pencil scrawled diary.[2]

John was educated at Camberwell Church of England Grammar School in Melbourne. This elite boys’ school was founded in 1886 and was ‘dedicated to educating young men for life.’ Despite its deep academic bent, it also had a particular focus on the arts, music, drama and sports. In 1888 an Army Cadet Unit was established at the school for pupils wishing to undertake military training. The school’s motto Spectemur Agendo - ‘By our deeds, may we be known’ encapsulates an undeniable ethos, and it is highly likely that de Crespigny’s schooling had a seminal influence on his later life. As a young adult, he voluntarily served as a commissioned lieutenant with the Citizens Military Forces. In his civilian career he worked as an advertising specialist.

In November 1932 at Kew, Victoria, John de Crespigny married Eleanor Lois Organ who was a hairdresser. It was however a marriage of convenience, as their son John was born three months later in January 1933 and the couple never lived together. Instead of setting up home with his wife and child, John resided with his mother Barbara in Ballarat, and for a while, with his older sister Annie Francis in Brighton. Eleanor filed for divorce in 1938 on the grounds of wilful desertion. According to the evidence she gave in court, John had been reluctant to pay separation maintenance and he had shown little interest in their young son. A divorce was duly granted in 1939 at the Supreme Court in Melbourne and Eleanor retained custody of John Jnr.

De Crespigny was living in the beachside suburb of St Kilda when he enlisted with the 2/6 Battalion AIF at the Command Recruiting Depot in South Melbourne on 29 February 1940. Perhaps, after his tumultuous years of marriage, he was much relieved when he ticked the ‘single’ box on the enlistment form and cited his mother as his next of kin. His very low service number – VX253 suggests he was amongst the first cohort of Victorian men to join the 2nd AIF. On 14 April 1940, Lieutenant Champion de Crespigny embarked on SS Neuralia which departed from Melbourne for Kantara, Egypt on the following day. Here he transferred to the 1st Australian Corps Guard Battalion and saw action during the Syrian Campaign.[3]

John was promoted to Captain in May 1941 and to Temporary Major in February 1942. In that same month he left Suez on board SS Orcades with some of his men from the Guard Battalion, along with other advance units of the 7th Division which were being re-deployed for the defence of Java. These units included the 2/3 Machine Gun Battalion, the 2/2 Pioneer Battalion and the 2/2 Casualty Clearing Station. Unfortunately, the Orcades’ arrival in Batavia, Java, coincided with the Japanese invasion of that island. Despite gallantly putting together a scratch force of defenders under Temporary Brigadier Arthur Seaforth Blackburn VC, known as ‘Blackforce’, resistance was ultimately futile and the Australians were ordered to capitulate. Early in March 1942, de Crespigny was reported as missing. Later various eye witness accounts suggested he had been killed resisting the Japanese on Java. But he had in fact become a POW on 9 March following the surrender of all Allied forces on Java on the previous day. Exactly a year later, he fulsomely exclaimed the following in his diary,

‘ONE BLOODY LONG YEAR AGO TODAY I WAS ORDERED BY THE C IN C TO LAY DOWN MY ARMS – I’LL NOT FORGET IT!!’[4]

In total 2736 men of the 2nd AIF became prisoners of the Japanese on Java. De Crespigny spent his early captivity at the sprawling Dutch Army barracks at the No 12 Bandoeng camp, West Java, with fellow Victorian, Lieutenant Colonel Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop of the Royal Australian Army Medical Corps. In November 1942, 1000 Australian prisoners, including Dunlop and de Crespigny, were moved to a camp at Makasura, Batavia where they shared quarters with British prisoners.

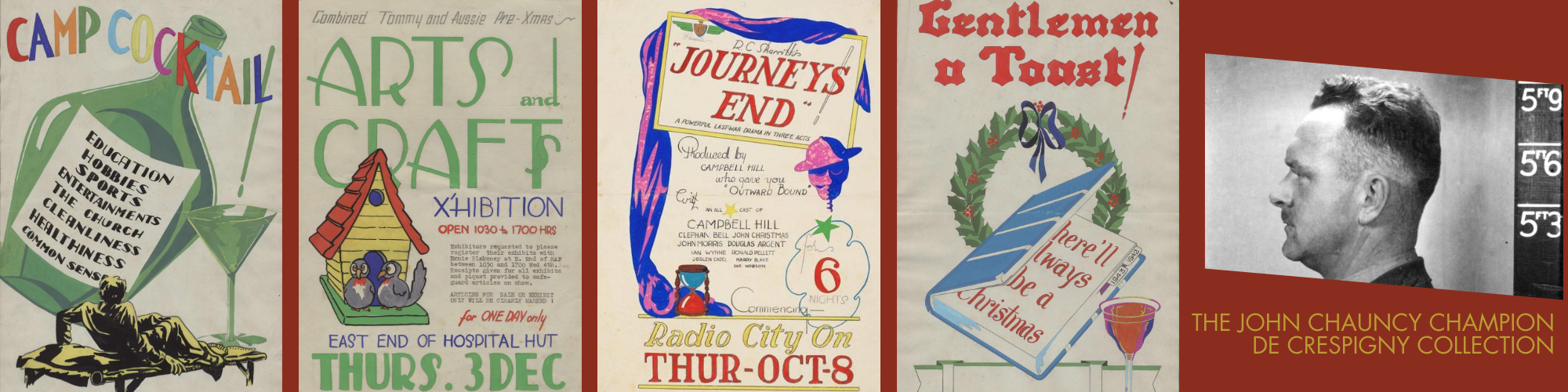

The senior Allied officers were aware that they were now engaged in a new war, ‘a war for physical and moral survival.’[5] Determined to keep their troops occupied and their morale up, they quickly established a range of activities to keep the camp inmates busy. Within a few weeks of arriving at Bandoeng, a wide range of lectures and educational classes had been organised, together with sporting activities, creative workshops and various societies for those with theatrical and musical interests. John de Crespigny was one of the leading instructors in the camp. He taught art classes and lectured on various aspects of advertising. He was also a talented writer and illustrator and worked tirelessly with a small creative team to produce hand drawn posters advertising various camp activities. De Crespigny played a central role in organising a number of arts and crafts exhibitions and the camp magazine, fittingly titled Mark Time was produced and illustrated under his expert guidance. It featured articles, cartoons and stories, together with camp news, rules and regulations. He was also instrumental in collecting written and artistic material from the Bandoeng and Makasura inmates, for the purposes of compiling a POW souvenir ‘Memorial Book’. The idea for this had been greatly inspired by the famous Anzac Book, published to much acclaim in 1916. Edited by Australia’s official war correspondent C.E.W. (Charles) Bean, the initial scripts of the Anzac Book were written and illustrated on scraps of paper by soldiers enduring extreme hardship under enemy fire in the bleak trenches and underground hell holes on the Gallipoli peninsula in 1915.

De Crespigny was absolutely determined that a similar record of the men’s time as prisoners in the current war (and perhaps also their extraordinary talents) be likewise recorded for posterity. The creating and collecting of material for the Memorial Book was, in the poignant words of its organizing committee, to,

‘give us a certain point to the apparent suspense of purpose in our lives, and help us to complete the spiritual and intellectual defeat of our barbed wire entanglement.’

Countless men sat for their portraits, wrote poems and stories and made sketches and drawings of their daily camp life. It was earnestly hoped that the book would be published in Australia after the war. For similar reasons, de Crespigny also secretly kept a series of meticulous and detailed diaries. On Wednesday 28 October 1942 he reflected why he undertook such an activity;

‘Unable to write letters, I find writing up this diary not only a method of each daily little event – which may recall memories in years to come (if I can get this book home) but it is excellent writing practice … and even if I never do get my volumes home, it has been fun keeping them up to date.’

On first meeting de Crespigny at the Bandoeng camp on 23 July 1942, Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop, who was also a prolific diarist, noted,

'Some good ideas came forth today, both of them from Maj. J. Champion de Crespigny … a commercial artist - thick-set, fair, Norman blue of eye, full of life and the lusts thereof. An arts and crafts society for all who can make things to be followed by an exhibition and sale of products: and a memorial souvenir book to parallel the old ANZAC volume - dedicated to comrades in arms in Java. We are producing a newspaper now and probably there will be good stuff forthcoming from it. Artists such as PO Ray Parkin are hard at work on the camp, and now a series of portraits is to be done with the help of a Dutch artist. I hope that it will be a true record of the manner in which the human spirit can rise above futility, nothingness and despair, since truly we were left here with nothing.'[6]

For a few short months in 1942, the prisoners at Bandoeng and Makasura did indeed ‘rise above futility, nothingness and despair.’ Yet tragically this state of affairs was not to last and as the war progressed, conditions for the men deteriorated as they were split up, formed into work parties, and moved from camp to camp. Early in 1943, many Australian prisoners, including Dunlop and de Crespigny, were relocated to Singapore and from here to the Konyu-Hintok Area near the Burma-Siam border. The men were congregated in squalid jungle camps and those below officer rank were made to work on the construction of the infamous 260-mile railway linking Thailand and Burma.[7] Following its completion in October 1943, the men were disbursed throughout South-East Asia. Some were sent to toil in Malaya, others to languish in Changi prison in Singapore. Many were relocated to Japan and forced to labour in mines and other heavy industries. The relative freedoms they had enjoyed at Bandoeng and Makasura were now long gone and life was instead characterised by ‘unmitigated cruelty and horror’.[8] Brutal treatment, over-work, starvation rations, insanitary living quarters, sickness and the ever-present threat of contagious diseases all conspired to bring death to thousands. More than 22,000 Australians became prisoners of the Imperial Japanese Army in South East Asia and more than 8000 of them died in captivity. Many more returned home physically maimed and carrying psychological scars that would remain with them for the rest of their lives.

Following the Japanese surrender in September 1945, de Crespigny was ‘recovered from the Japanese at Siam.’ He sailed for Melbourne via Singapore on 17 October 1945 and was discharged from the army as an Honorary Major in December that year. In 1949 he was awarded an Efficiency Decoration medal for his long volunteer military service.[9] On his return, he provided a sworn statement to the inter-Allied team investigating Japanese war crimes. The war crimes trials heard appalling stories of atrocities and massacres including the infamous ‘death marches’ that had been callously perpetrated by the Japanese on many of their hapless Allied prisoners. De Crespigny’s acute memory and the scrupulous but covert recordkeeping he had maintained in his diaries during his captivity allowed him to identify some of the more brutal captors so that they could be brought to justice. The trials also heard how on far too many occasions, simple medical negligence and indifference had led to much unnecessary misery and death. ‘Weary’ Dunlop had noted in his diary on 2 June 1943 that, ‘Suffering is written deeply in the faces and frames of almost everyone in this camp and there are many who cannot stand much more…’. De Crespigny also recorded many distressing instances of neglect. On 21 August 1943 he wrote,

‘Today I had a look at the ulcers on the legs of a man named Abbot (26 Coy). He is almost a skeleton and both ulcers have eaten away to the bones – a frightful sight and decidedly ‘on the nose’. It is probable he will have to have both legs amputated – one for certain…It makes one bitter and defiant to watch men rot and die like this – it is all so needless – just plain murder from deliberate brutality and enemy negligence. The medical people here are up against a colossal wall of indifference and obstruction. Nippon medical admin would be laughable if it wasn’t so pitifully tragic. The ignorance and stupidity of all their medical personnel is exasperatingly unavoidable…’

After the war, John de Crespigny settled at Hawthorne in Victoria and worked as an advertising manager for the rest of his career. By the middle of 1946 he was actively involved with ‘Weary’ Dunlop in the Victorian branch of the Australian POW Relatives Association. And in June 1947 he remarried and happily this marriage was genuine and long lasting. His bride, Margaret Serisier nee Nichol (1909-1998) was a war widow with two teen-aged children. Her feted first husband was VX62337 Colonel Esmond Bernard Serisier who was a graduate of the Royal Military College, Duntroon. During the Pacific War, Serisier had served in New Britain and in New Guinea where he received a Mention in Despatches in 1943. By 1945 he was the Senior Officer in charge of demobilisation for all three services. Serisier died very suddenly at the family home in Melbourne on 25 September 1945 at the relatively young age of forty.

Despite their long and successful marriage, John and Margaret did not have any children of their own. John died on 7 February 1995, aged 82 years. Just three months after his death in June 1995, his widow Margaret wrote to the Australian Army and applied for his Africa Star Medal. Why de Crespigny himself had not claimed his rightful war decoration is something of a puzzle. The medal was issued in June 1996. Margaret de Crespigny died in 1998.

In 1997, twenty-four POW camp posters from Bandoeng and Makasura, numerous copies of Mark Time, John de Crespigny’s wartime diaries and many pieces that had been penned and drawn for the planned souvenir Memorial Book were donated to the Anzac Memorial by de Crespigny’s step-son.[10] That these delicate paper artefacts survived the jungle camps of South-East Asia and were later brought back to Australia is astonishing. Some of this extraordinary collection is currently on display in the Anzac Memorial’s temporary exhibition 1945 Hot War to Cold War. It is the first time this remarkable material has been made available for public viewing. De Crespigny’s school motto, Spectemur Agendo - ‘By our deeds, may we be known’, has certainly come full circle. And we hope that he would have been proud that seventy-five years later, this incredible story is finally being told.

FOOTNOTES

[1] De Crespigny enlisted a little over three weeks before the second conscription referendum which was held on 20 December 1917. It is possible that he had been swayed to enlist (before he was potentially conscripted) by the massive outpouring of propaganda which had saturated the country – on both sides of this very contentious and divisive issue.

[2] John de Crespigny, Diary entry, Tuesday 14 July 1942.

[3] His older brother Lieutenant (later Captain) Philip George Champion de Crespigny, VX14856, enlisted on 13 May 1940. He was initially sent to Palestine but was re-deployed to Australia in August 1942 and spent the rest of his war in Queensland with the 3 Army Ordinance Depot.

[4] John de Crespigny, Diary entry, Tuesday 9 March 1943.

[5] Colonel Sir Laurens van der Post, Foreword, in E. E. Dunlop, The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop, Java and the Burma-Thailand Railway 1942-1945, Nelson, Melbourne, 1986, p x.

[6] E. E. Dunlop, The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop, Java and the Burma-Thailand Railway 1942-1945, Nelson, Melbourne, 1986, Diary entry, Thursday 23 July 1942, p 71.

[7] Some 65,000 POW, together with a much greater, but still unknown number of conscripted Asian labourers worked on the railway; approximately 12,000 POW died. Of the estimated 9500 Australian POW who were put to work on the railway, over 2500 died of disease, starvation and ill-treatment. Siam changed its name to Thailand in 1939, although Australian military record keepers still often referred to it by its previous moniker.

[8] Colonel Sir Laurens van der Post, Foreword, in E. E. Dunlop, The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop, Java and the Burma-Thailand Railway 1942-1945, Nelson, Melbourne, 1986, p xiv.

[9] His Efficiency Decoration medal was stolen in April 1977 from his home in Hawthorne, Victoria and he wrote to the Army’s HQ in Melbourne requesting a replacement.

[10] In 1955 John de Crespigny lent his diaries to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra for the purposes of contributing to the research and writing of the official history of the Second World War.