To alleviate boredom and to contribute to maintaining morale at Bandoeng, the British prisoners in the camp set up the ‘British Theatrical Company’. Their logo ‘BTC’ appears on the posters associated with the productions they organised. They performed plays – such as Julius Caesar in July 1942, but also music hall events, comedy shows, amateur hours, ‘mock’ trials, pantomimes, stage skits, one act plays and variations on British vaudeville. There was no lack of thespian talent among those involved with the BTC, with both professional and amateur actors being available to show off their skills. The directors of the two plays featured here, Clepham ‘Tinkle’ Bell and Campbell Hill were both well-educated gentlemen who had been actors in Britain before the war. Bell in particular had a ‘booming theatrical ‘Old Vic’ voice’.[1] The BTC was enthusiastic in its productions, and they were greatly appreciated by the inmates of all nations. Prior to their departure in late October 1942, the ‘Ambonese guitarists’ had often featured in their musical shows. Some of their acts involved female characters, and naturally, the ‘leading ladies’ often created quite a stir and much hilarity amongst the camp audience. Costumes and props were improvised, borrowed and on occasion, kindly donated by the local free Bandoeng community. Posters and stage backdrops were designed by de Crespigny and crafted with his small team of artists, producing their eye catching and at times, thought provoking posters to advertise an up and coming BTC event. The production of every show, from props to performers, was an exercise in collaboration, team work and co-operation. And it was all carried out with a spirit of comradeship and mutual respect that crossed nationalities, ranks and classes.

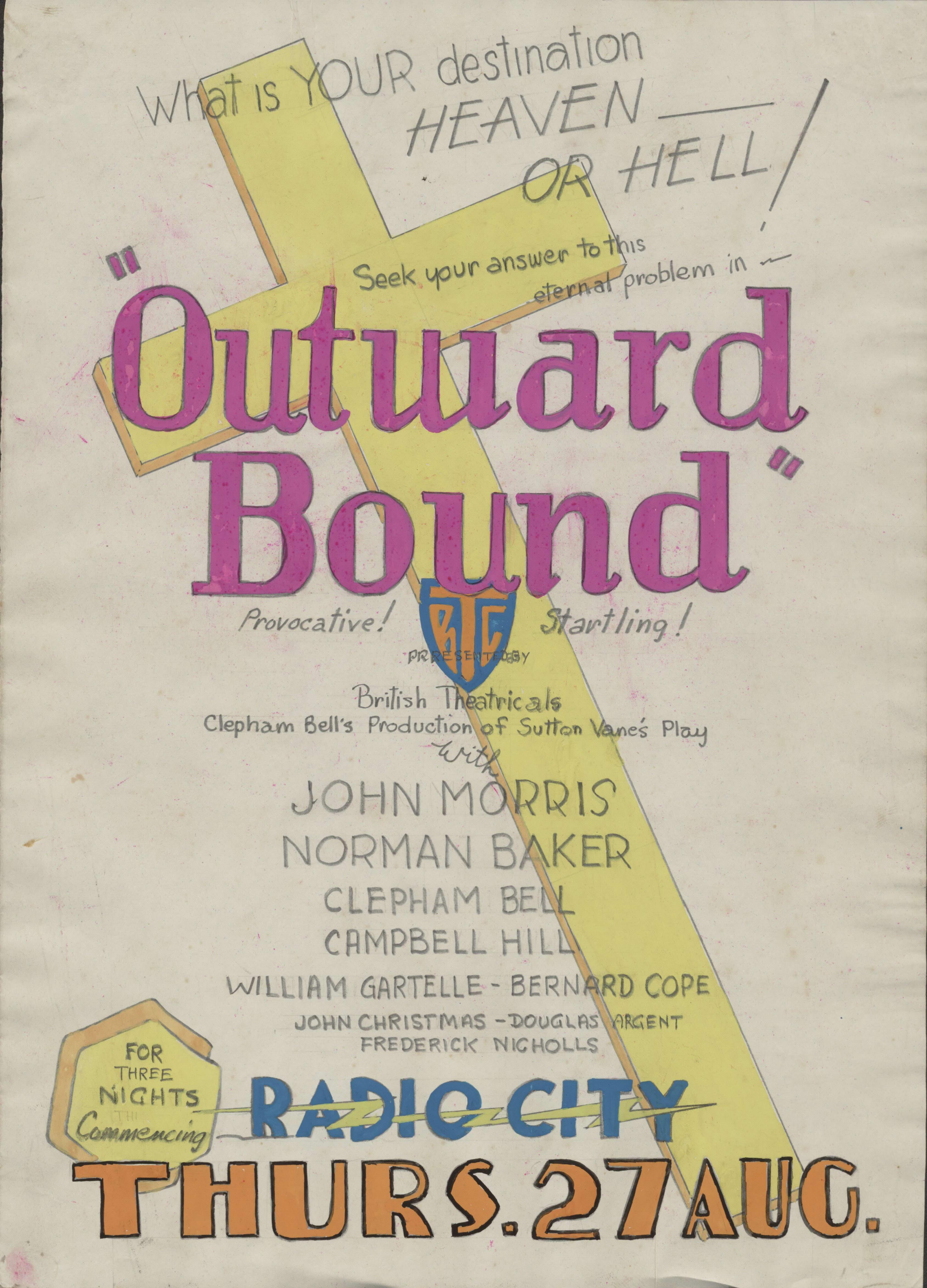

The play Outward Bound was supposed to have been performed for three nights from Thursday 27 August 1942 at the Radio City venue. However the opening show was delayed because ‘Tinkle’ Bell went down with ‘severe’ dysentery and was evacuated to hospital and so the show ran on into September.[2] Outward Bound had first been staged in London in 1923 and would have been familiar to many of the British Commonwealth men, as it had been an instant West-End hit.[3] Written by Great War veteran, Vane Hunt Sutton-Vane, and combining drama, fantasy and a touch of comedy, the play is about a disparate group of eight passengers who meet in the lounge of an ocean liner at sea. They have no idea why they are there or where they are going. Eventually they work out that they are all in fact dead and will soon be called to account for their lives before a mysterious Examiner. The main drama revolves around the central premise - Who was going to heaven? Who was going to hell?

The author, who wrote under the pen name Sutton Vane, enlisted in the British Army in 1914 at the age of 26. He was commissioned into the Army Service Corps as a temporary second lieutenant in July 1915, but was later invalided out suffering from malaria and shell shock. When he recovered in late 1917, he returned to the Western Front as a performer in one of the many travelling concert parties which provided entertainment for the front-line troops. These theatrical troupes put on musical performances, stand-up comedy, topical skits and well-known pantomimes – all part of the rich genre of music hall tradition so beloved by the British at the time.

The ‘provocative’ and ‘startling’ play would have been relatively simple to produce in the barracks setting at Bandoeng with minimum props required for a single stage set. John de Crespigny designed a set of posters to advertise the performance and he also painted (in his own words), a ‘remarkably lifelike’ oceanic backdrop for additional atmospheric scenery. Three of the characters in the play were women and their costumes and makeup were probably obtained from local resources in Bandoeng. The performances no doubt produced some soul searching and possibly also some philosophical discussion among the prisoners along the lines of ‘in the midst of life we are in death’ and ‘where to from here?’

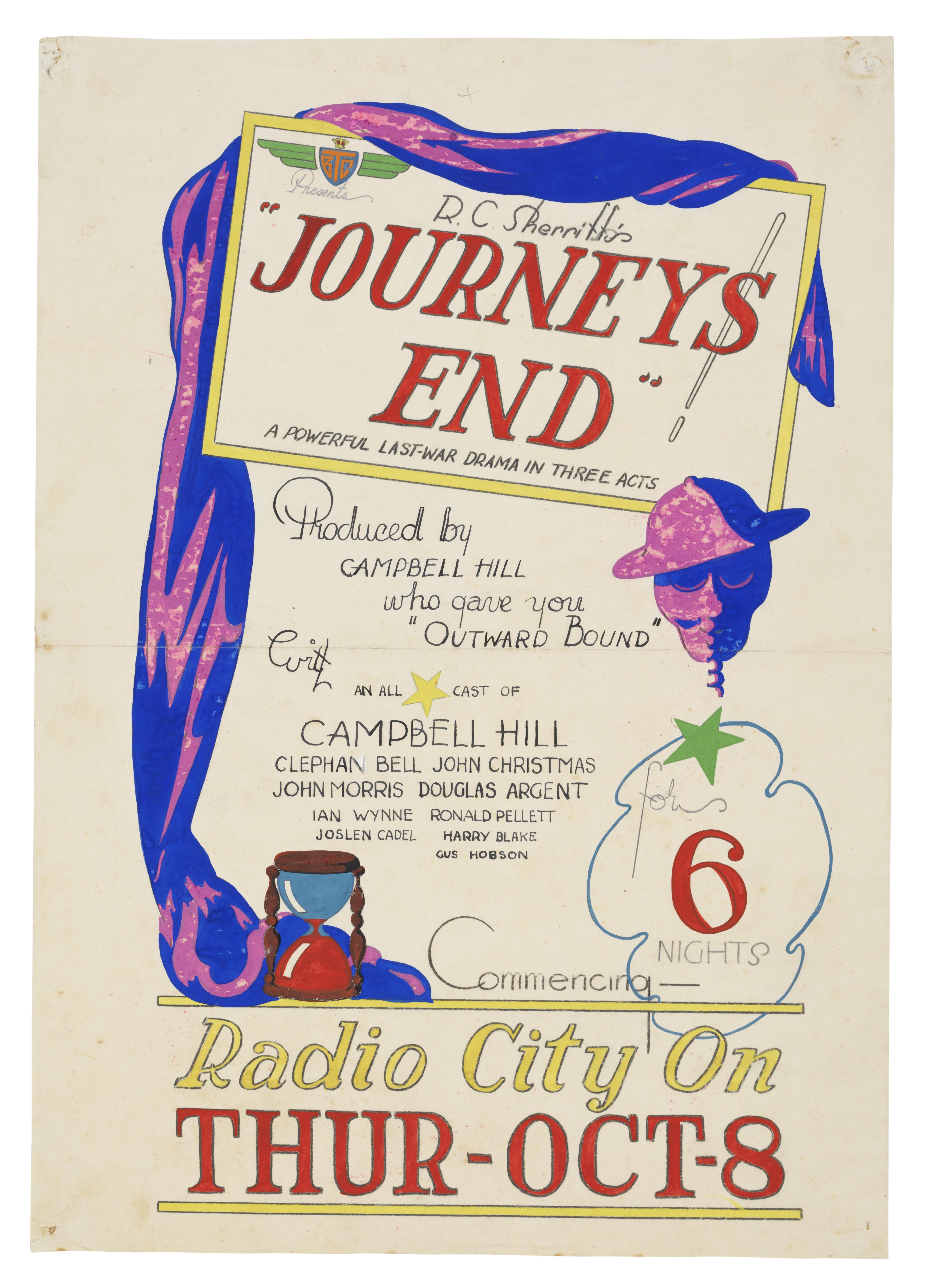

The play Journey’s End was performed at Radio City for six nights from Thursday 8 October. As with Outward Bound, it would have been familiar to many Commonwealth men and perhaps less so to those from other countries. Yet the theme for all would have been a universal one – the pointlessness of war.

The powerful drama is set in the First World War in an underground infantry company commander’s bunker on the front-line trenches near St Quentin on the Western Front. It depicts three days in March 1918, and the underlying theme is how each of the officers reacts to the pressures of the German Spring Offensive they know is coming. Of particular poignancy is the relationship between the hard-bitten, whisky-drinking but long-surviving company commander Captain Stanhope and the new young subaltern Second Lieutenant Raleigh, whose sister Madge is a good friend of Stanhope’s from before the war.

The author, Robert Cedric Sherriff was an 18-year-old insurance clerk at the outbreak of the Great War. He enlisted and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 9th Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment. He fought at Vimy Ridge and Loos and was later severely wounded at Passchendaele in 1917. Sherriff wrote Journey’s End in 1928 and based it on his own experiences of the war. In December 1928, the first stage production saw a 21-year-old Laurence Olivier play the lead role of the young hopeful Raleigh, straight out of school and facing imminent death on the Western Front. The play was immediately popular with the British public, because they identified with its themes of war-weariness and lives wasted. It received excellent reviews, however there was some criticism in the theatrical community that it lacked a leading lady (there are no women in the script, except by inference to Madge, Raleigh’s sister). This prompted Sherriff to later title his 1968 autobiography No Leading Lady.[4]

The play, mostly set in a bunker, would have been simple to stage at Bandoeng with the stage sets, uniforms and props easy to reproduce. There were plenty of men with acting and theatrical experience in the camp and perhaps a copy of the play was borrowed from the lending library to help with the script and direction. The profound and heartfelt sadness of Journey’s End with its central themes of war as futile and wasteful, must have elicited deep reflection for many audience members. We can however only speculate what the Japanese officers and guards thought about the prisoners putting on a play about a previous war in which they had been allies of their current enemies and prisoners.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Tragically Bell silenced his voice forever when he slit his own throat early in 1943, the pressures of POW life too much to bear. E. E. Dunlop, The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop; Java and the Burma-Thailand Railway 1942-1945, Nelson, Victoria, 1996, Diary entry, Thursday 15 October 1942, p 104.

[2] E. E. Dunlop, The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop; Java and the Burma-Thailand Railway 1942-1945, Nelson, Victoria, 1996, Diary entry, Wednesday 26 August 1942, p 83.

[3] It was the biggest show on the London stage in 1923. It went to Broadway in 1924 and was turned into a film in 1930 with Douglas Fairbanks Jr in one of the roles.

[4] The stage play has been very popular through the decades since and has had several screen adaptions, the most recent being made in 2018. Sherriff himself went on to write more plays, screenplays and novels and was nominated for an Academy award in 1939 and a BAFTA award in 1955.