The Greek island of Lemnos, in the north-eastern Aegean Sea, became a major base for the British empire forces involved in the invasion of Gallipoli. Though Greece was not yet a combatant on the Entente side (it declared war only in June 1917) its government was sympathetic to the Entente, especially in prosecuting the war against Greece’s traditional enemy, the Ottoman empire. The two had recently fought in the first Balkan war 1912-13, in which the Greeks had occupied formerly Turkish Aegean islands, including Lemnos.

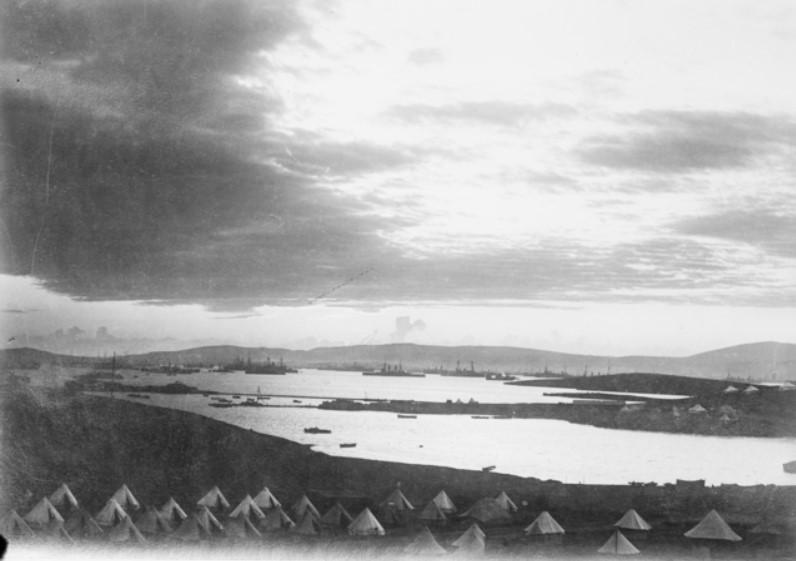

Image: Dawn at Lemnos 1915. Tents of the camp in the foreground and ships in the harbour. AWM A02706.

Located within 100 kilometres of the Gallipoli peninsula, Lemnos was well situated to form an advanced base for the Entente’s planned invasion, and in February 1915 the Greek government of Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, offered its support to military operations against the Ottoman empire. The island, low and largely treeless, is about 30 kilometres long, notable for its windmills. It is almost bisected by the huge Mudros harbour, which became the anchorage for the invasion fleet.

By mid-April the harbour saw the arrival of dozens of British and French warships, and over a hundred transports and merchant ships. Many Australians who were to take part in the Gallipoli landings spent several weeks camped around the harbour, making route marches around the island and practising handling the ships’ boats in which they would land on the peninsula. Australian battalions also visited the volcanic hot springs located in the centre of the island at a village fittingly named Therma, in the island’s south-west.

Image: A practise landing at Lemnos, April 1915. AWM A03224.

Lemnos was not just the point of departure for the tragic and ultimately futile invasion of Gallipoli. It became a subsidiary logistic base for the campaign, with supply units, reinforcement camps and hospitals. The island’s lack of water made it unsuitable as a large base, and the island of Imbros, only 30 kilometres from Gallipoli, became the main base. Early in the campaign its logistics was poorly organised – troops joked that they were ‘Lemnos, Imbros and Chaos.’

A tented Australian Rest Camp was established on the western shore of the harbour at the village of Sarpi. The other main Australian connections with the island are the hospitals that operated there in 1915, and the island’s Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries.

The hospitals located on Lemnos included the 1st and 2nd Australian Stationary Hospitals, established on the island from March and June 1915, and later the 3rd Australian General Hospital. Situated on a peninsula (Cape Pounda, then also called Turk’s Head or Millar Point) jutting into the harbour, all were housed in tents; by August 1915 they were holding up to a thousand patients at any time. While intended to treat only lightly wounded men, the disorganised medical arrangements often saw the arrival on Lemnos of badly wounded casualties.

Image: Nurses of No 3 Australian General Hospital about to follow a piper into their camp, under the leadership of their matron, Miss Grace Margaret Wilson and second in command of the hospital, Lieutenant-Colonel J A Dick at Mudros West. August 1915, AWM A04118.

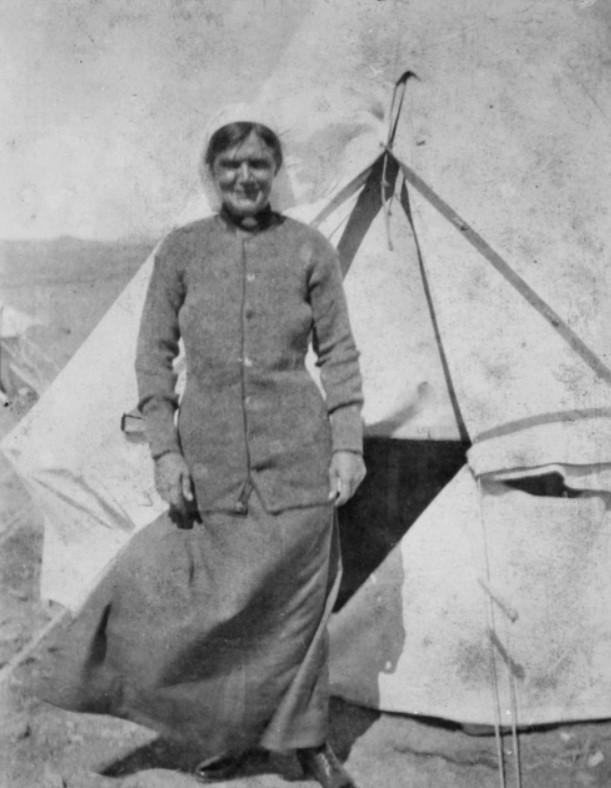

The 3rd Australian General Hospital opened on 2 August 1915, just in time to receive casualties from the failed and costly August offensive. Its matron, Grace Wilson, recorded her horror at finding the first patients lying on the ground, without water, whom for days nurses had to clean using their own soap and towels. ‘A good many died’, she wrote, ‘it is just too awful.’

Image: Matron Grace Margaret Wilson (later Mrs B Campbell) outside her 'office' at No 3 Australian General Hospital. Matron Wilson served as a senior matron during the First World War and Matron in Chief during the early part of the Second World War. AWM A05331.

Conditions were indeed harsh. One Australian nurse described them as ‘primitive’; patients and medical staff lived in tents, which was a trial in the island’s hot summer and also during the bitter winter. Both seasons suffered from the ‘meltimia’, the island’s relentless wind. While nurses slept for a time on blankets on the bare ground, the staff on the headquarters ship Aragon, anchored in Mudros harbour, enjoyed good food, baths and bedsheets. Resentful comments about the Aragon sardonically described as the ‘Enchanted Island’ appear in some diaries.

Image: Medical and nursing sisters of No. 3 Australian General Hospital in the tent lines with patients. AWM J01438.

Lemnos also housed one of the two main Canadian contributions to the campaign (in addition to the Newfoundland Regiment’s service at Suvla), in the establishment of the 1st and 3rd Canadian Stationary Hospitals which, like the Australian hospitals, treated casualties regardless of nationality. Two Canadian nurses died of illness in 1915 and they were buried in the island’s war cemeteries. By January 1916 all of the island’s remaining patients and medical staff had left for Egypt.

Image: Mudros cemetery containing the graves of Allied soldiers who were killed in the Gallipoli Campaign. A memorial stands in the background. One of a series of photographs taken on the Gallipoli Peninsula under the direction of Captain C. E. W. Bean of the Australian Historical Mission, during the months of February and March, 1919. AWM G02072.

There are three war cemeteries on Lemnos and 145 Australian soldiers are buried in two of them, at Portianos and East Mudros, both approached by roads later renamed ‘Anzac Street.’ The cemetery at East Mudros also holds the remains of 170 Egyptian labourers and 57 Turkish prisoners who died of their wounds on the island.

East Mudros cemetery is situated on the east side of Mudros Bay, above the small town of Mudros beside the Greek Civil Cemetery. Begun in April 1915, it was used until September 1919 and contains 919 mostly British empire dead, of whom 95 are Australian. The cemetery also includes memorials to Russian and French dead. The French dead were later removed to the main French cemetery on Gallipoli. The Russians, among the 5000 émigrés who arrived post-war, suffered 350 deaths from illness.

The village of Portianos is on the west side of Mudros Bay, on Anzac Street, adjacent to the communal cemetery. Fifty Australians are among the 347 burials in Portianos cemetery, overwhelmingly men wounded in the fighting on Gallipoli who subsequently died, and others who succumbed to illness.

After 1915, Lemnos left the mainstream of Great War history, but in 1918 it became the setting for the signing of the Armistice of Mudros, signed aboard the British battleship HMS Agamemnon, again, in Mudros harbour, on 30 October 1918. That treaty was portentous for the future of millions of people in the region as the belligerent states made the long and difficult transition from war to peace. As many Greeks here will know, the years that followed the armistice brought the forcible eviction of hundreds of thousands of Greeks from former Ottoman lands to Greece, and of course the transfer of Turks to the new Turkish republic.

Today, there is little popular memory of Lemnos in Australia. Australians largely do not know about the brief encounter with the small island and its people in 1915. Australian newspapers made very few references to Lemnos until in 1915 the number soared: 63 mentions in 1914, but over 5,000 in 1915. By 1919, though, the number fell again to 500 – still ten times the annual figure before the war.

The relationship between Lemnos and Australia has been commemorated in recent years. Especially during the Great War centenary, there have been various exhibitions, statues, memorials and books, and all have helped to develop knowledge of the historical relationship. Limnians, who sponsor conferences and books to celebrate the wartime relationship with Australia, feel frustrated that most Australians, even those interested in Gallipoli, know little about Lemnos, and that few ever visit. They almost invariably approach Gallipoli from Istanbul: sadly, Lemnos attracts only those with a direct personal connection or those with a specialist interest.

Further reading

Jim Claven’s llustrated Lemnos & Gallipoli (2019) is the most recent Greek-Australian collaboration on the island’s Anzac connections.

Michael Tyquin’s Gallipoli: the Medical War (1993) deals with Lemnos’s part in the wider story of medicine and the campaign.

Jan Bassett’s Guns and Brooches (1992) offers the most authoritative account of the nurses’ trials on Lemnos.

Anyone intending to visit Lemnos should consult Roger Hawthorn and Tony Whitefield’s A Lemnos Odyssey (2015) which covers the island’s Classical history, and details of its part in the Great War, including suggestions on sites to visit. It should be read in conjunction with Phil Taylor and Pam Cupper’s Gallipoli: A Battlefield Guide which though published in 1989 remains the best overall guide to the campaign, including the Greek islands associated with it.