This red wool cape and brown leather belt were generously donated to the Anzac Memorial in 2021. They had once belonged to Florence McMillan who was one of the first women to serve during the Great War. McMillan was the great aunt of the donor.[1]

Florence Elizabeth ‘Betha’ McMillan was born on 21 January 1882 in Burwood. Her parents were Ada Charlotte nee Graham and (later Sir) William McMillan who was a merchant and highly esteemed politician. Betha attended Claremont College in Randwick and later studied art in Paris. After extensive travelling in America, Ireland and South Africa which she described as ‘relatively aimless activity’ in 1909 she commenced training as a nurse at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (RPAH) in Sydney. She was registered by the Australasian Trained Nurses Association in 1913 and qualified as a sister the following year.

War breaks out

On the outbreak of the Great War, McMillan was one of six nursing sisters from the RPAH who sailed in the hospital ship, HMAS Grantala, to support the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) in German New Guinea.[2] The Grantala sailed out of Sydney Harbour on 30 August 1914. In October the ship left Blanche Bay off Rabaul and journeyed to Suva in Fiji, returning to Sydney in time for Christmas 1914.

Photo: Group portrait of the sick bay staff from the Grantala. Elizabeth McMillan is the second nurse on the left. AWM 302802.

In April 1915 Betha transferred to the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) and embarked for Europe per SS Mooltan on 15 May 1915. The ship sailed into Plymouth in Devon on the south coast of England on 27 June and Betha travelled by rail to London, later catching a train to Manchester where her much loved younger brother Gibson was recovering from an eye injury. Gibson McMillan was born in Sydney in 1883 but was living in the Bay of Islands on the North Island of New Zealand when the Great War broke out. He enlisted in Auckland as a trooper with the Mounted Rifles, 11th Regiment, New Zealand Expeditionary Force, on 16 September 1914. Whilst training in Egypt in February 1915, Gibson was accidentally injured when a stone, propelled by a horse in front of him, entered his right eye. He was sent to England and spent the rest of his war there. He was discharged from the military in May 1916, his eye having completely lost its sight.[3]

Tending to the Gallipoli wounded on Lemnos

In July 1915 Betha and her fellow nursing sisters were informed that they would be serving with the 3rd Australian General Hospital under Colonel Thomas Fiaschi and Matron Grace Wilson on the Greek island of Lemnos. The guns at Gallipoli were just sixty miles away and hospital ships aside, the island was the closest location to Gallipoli where nurses could serve during the planned August 1915 offensive. The proximity seemed to stir intense emotions for some of the women. Staff Nurse Nell Pike, from Sydney ‘could imagine no greater joy than to be working under the canvas so close to the gallant men of Anzac.’[4]

Two Australian military hospitals were already in operation on Lemnos. Yet conditions on the barren windswept island were far from ideal and the nurses attached to the third hospital had to wait three long weeks for their equipment, tents and medicines to arrive after they landed on 9 August. Caring for the wounded in the open air with few essential supplies such as bandages and clean water to drink or wash in was tremendously difficult whilst the sheer weight of the sick and injured was deeply burdensome. On 23 August 1915 Betha wrote a letter home in which she described her first couple of weeks on the island:

‘The lack of any food but bully beef and hard ration biscuits; badly made tea; condensed milk; no kerosene for Primus stove or methylated spirits. Bread sour, made at the Ration bake house but which gives diarrhoea if eaten; swarms of slow persistent flies; boiling sun though cool by night. All patients on mattresses on the earth; the constant kneeling and lifting from that position; no clean clothing; nursing them in their gore-soaked clothes; add up a few of the difficulties against which we have been fighting.’[5]

It was all a far cry from the well-appointed RPAH where Betha had trained as a nurse. Other difficulties included no bathing facilities and a poor water supply which made sanitary conditions exceedingly grim and together with a thoroughly inadequate diet, dysentery (or ‘Lemnitis’ as it was known) was rife. As winter neared and the weather turned bitterly cold, mud and wind and the lack of fuel for heating further tested the nurses endurance on the island. Despite calls for improvements to be made, by late November the women were still housed in unlined bell tents and warm winter uniforms were yet to arrive. In his Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, Colonel Arthur Graham Butler DSO deeply sympathised with the nurses plight, but also generously acknowledged their extraordinary ability to carry on with their vital work regardless:

‘The conditions under which the nursing sisters worked both now [August] and for some time later, at Lemnos were more crude than any met with afterwards, perhaps than any in the war. The physical discomforts were great; the heat was intense. Bell tents they had, mattresses and bedding and “hard” army ration, but little else. Facilities for personal cleanliness were primitive. But it was clearly in connection with their professional work that the women were tested to the utmost…It is clear [however] that the training in the nursing profession, severe beyond most in its standards of toil, self-discipline and resource in compelling order out of chaos, enabled these trained women to adapt themselves (as they have often before) to circumstances, bend to clearly recognised ends, such means as could be found, and in a short time obtain a mastery of the situation.’[6]

Photo: Medical and nursing sisters of No. 3 Australian General Hospital in the tent lines with patients. AWM J01438.

Despite the difficulties, Betha, like many of the nursing sisters felt working on Lemnos to be a tremendous honour and privilege and to ‘share in a slight way the hardships of our brave soldiers.’[7] The decision by Lord Kitchener to evacuate all troops from the Dardanelles in November 1915 meant that the canvas tent hospitals on Lemnos would eventually become redundant. Since August Betha and her fellow nursing sisters had, despite their initial difficulties, treated thousands of patients with a death rate of just two and a half percent.[8] The Honorary Assistant Surgeon from Sydney’s RPAH, Major John Morton who was on Lemnos, paid tribute to the nurses’ work on the island. According to Morton:

‘They did splendid service and have established themselves as a necessary factor in military organisation. I feel sure that no one who had experienced what the nurses meant to the sick at Lemnos could again tolerate the system of nursing by [male] orderlies.’[9]

Following a relatively quiet Christmas on the island, the staff and patients from No. 3 Australian General Hospital were transferred to Egypt on 20 January 1916. Betha spent the rest of the war working in hospitals in Egypt, England and France.

Photo: Evacuation of patients and staff from No. 3 Australian General Hospital on Lemnos to Egypt, January 1916. AWM J01501.

Between March and June 1919, Betha was in London on leave with pay, awaiting repatriation. With so many ships lost to submarines, torpedoes and mines during the war, tens of thousands of Australians had many months to wait before they could return home. Betha took advantage of the AIF non-military employment scheme which kept the Australians stranded overseas usefully occupied by furthering their education and improving their future work prospects. More than three hundred nursing sisters took up opportunities to gain skills that would be useful to their post-war lives such as midwifery and learning to drive. Betha enrolled in a mothercraft training course set up by Dr (later Sir) Frederick Truby King at the Babies of the Empire Home and Training School in Earl’s Court, London. Here she learnt how to advise and help mothers practise good infant feeding methods which were necessary to reduce the dreadfully high infant mortality rate that was still all too common, particularly amongst the poor.

Building a post-war life in Australia

McMillan returned to Australia per Port Lincoln in charge of the nursing staff on board and arrived back in Sydney on 20 September 1919. On 19 November 1919 she received her discharge from the AIF and went back to work at the RPAH, this time in the children’s ward. Her interest in babies and children remained firm and by 1922 she was the director of the Tresillian Mothercraft Training Centre in Petersham which had been established by the Royal Society for the Welfare of Mothers and Babies to train nurses for baby clinics. In 1923 Betha became the director of the Australian Mothercraft Society and supervised the nurses at Karitane, the society’s training school at Coogee, leading the public health crusade to improve infant health in NSW in the post-war years.

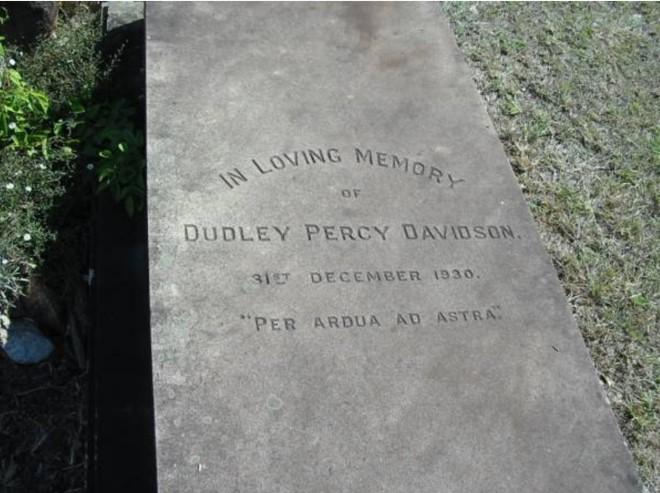

On 8 November 1929 Betha McMillan married Lieutenant Dudley Percy Davidson at St Andrew’s Cathedral in Sydney. English born and Cambridge University educated, Davidson was fifteen years her junior and the son of Vice Admiral Alexander Percy Davidson DSO of HMS Cornwallis. During the Great War, Dudley had served as a member of the Royal Naval Air Service and on his arrival in Australia in 1923 he joined the RAAF. By 1929, Davidson was a pilot with the newly-established company Queensland Air Navigation Co. Ltd. After their Sydney wedding the couple moved to Brisbane. Tragically just over a year later, Davidson was killed in an air crash at Maryborough on 31 December 1930.

Photo: Image courtesy of Gods Acre Cemetery, Archerfield, Brisbane.

After Dudley’s death, Betha returned to Sydney and wrote mothercraft columns for the Sunday edition of the Sun newspaper under the name of Elizabeth McMillan Davidson. She did not remarry and died on 9 February 1943 at her Woollahra home, her death certificate stating the cause of death to be aortic aneurysm. She was buried next to her older brother William at Waverly Cemetery. A short yet significant column printed in the Sun the day after her death called her a ‘leader in mothercraft’ and noted that the value of her work for the mothers and babies of Australia had been ‘incalculable.’[10]

Endnotes

- McMillan marked the inside of the belt with some of the places and dates where she served during the war; Lemnos 1915, Cairo 1916, France 1917-1919. In the 1930s her niece Eleanor ‘Jake’ Winifred Owen (the donor’s mother) visited Europe and took the same belt with her. Owen added Sydney 1932 and England 1933 to the inside of the belt to commemorate her overseas sojourn.

- Under Matron Sarah de Mestre, the six nurses were Rosa Kirkcaldie, Stella Colless, Bertha Burtinshaw, Elizabeth McMillan, Rachel Clouston and Constance Neale.

- Gibson McMillan died of dengue fever in New Britain in October 1922.

- Cited in Peter Rees, Anzac Girls; An Extraordinary Story of World War One Nurses, Allen & Unwin, London, 2015 (first published as The Other Anzacs in 2008), p 101.

- Betha wrote many letters home whilst she was serving overseas during the Great War. The letters were donated to the State Library of NSW in 1970. Cited in Clare Ashton, The Life and Letters of Elizabeth McMillan, 1882-1943, Anchor Books Australia, 2021, p 47.

- A. G. Butler, Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services 1914-18, Volume 1, AWM, Melbourne 1930, pp 337-38.

- Cited in Clare Ashton, The Life and Letters of Elizabeth McMillan, 1882-1943, Anchor Books Australia, 2021, p 123.

- Peter Rees, Anzac Girls; An Extraordinary Story of World War One Nurses, Allen & Unwin, London, 2015 (first published as The Other Anzacs in 2008), p 110.

- Cited in Peter Rees, Anzac Girls; An Extraordinary Story of World War One Nurses, Allen & Unwin, London, 2015 (first published as The Other Anzacs in 2008), p 110.

- ‘Leader in Mothercraft’, the Sun, Wednesday 10 February 1943, p 2.