Eighty years ago, a vast war consumed Asia and the Pacific.

In December 1941, having pursued an aggressive war in China for a decade, Imperial Japan at last unleashed a war of conquest against the European empires of Asia.

Launching simultaneous attacks on British and American possessions in Malaya and Hawaii on 7-8 December 1941, Japanese forces invaded European colonies in the Philippines, Hong Kong, Malaya, the Netherlands East Indies, Burma and, from January 1942, against Australia’s territories in New Guinea and its adjoining islands.

Photo: Darwin, Northern Territory, August 1942. RAAF members of a bomber squadron discuss an operation against Japanese bases in the Pacific. AWM 150391.

Australian forces in the Pacific

Australian forces became involved in the war from the outset, meeting Japanese troops in Malaya and Singapore, which capitulated in February 1942 with the capture of a huge Allied army, including 15,000 Australians. Small Australian forces had been posted across what was optimistically called the ‘Malay Barrier’, but these outposts, in Ambon, Timor and Java, soon fell to larger Japanese forces. The Australian defenders of New Britain and New Ireland were also overwhelmed and captured, with Japanese troops massacring their prisoners at Tol (New Britain), Kavieng (New Ireland) and at Banka (off Sumatra), when nurses fleeing from Singapore were murdered.

On 19 February 1942, Darwin, the main Allied base in northern Australia, was bombed, killing about 250 men and women, including Australian servicemen and civilians, and the port’s American defenders. The bombing of Darwin saw the beginning of a series of Japanese air attacks across northern Australia.

Photo: The Police Barracks and Government Offices in Darwin after being hit by several bombs during the air raid by the Japanese on 19 February 1942. AWM 026987.

While the Japanese debated but decided against invading Australia, preferring to continue their advance into Burma and to focus on defeating American naval strength in the Pacific, Australians understandably feared imminent invasion. It was not until the middle of the year that Allied code-breakers learnt that the Japanese did not intend to invade, and the Australian public were not told that invasion was unlikely until the middle of 1943.

The Japanese advance to New Guinea

Within five months, the Japanese advance had succeeded in conquering almost all of South-East Asia, and its forces continued to advance into Burma. From their new base in Rabaul, the Japanese were poised to take the final links in the chain that they planned would become their new defensive perimeter in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. These islands, and the Pacific Ocean, would become the setting for the battles later in 1942 which would determine whether Japan’s plans for conquest would continue or whether the Allies would hold their offensives in order to win back the lost territories and defeat Japan.

By April 1942 the initial Japanese advance had halted, as its forces re-grouped after its lightning conquests, while the Allies also recuperated after a series of defeats, gathering strength for the next phase of the war. Australia accelerated munitions, ship and aircraft production and procurement, mobilised its Militia force and welcomed back two of the three Australian Imperial Force divisions, returned from the Middle East by Winston Churchill early in 1942. Australia swiftly became a base for American forces, and in March 1942 General Douglas MacArthur arrived in Australia to become the Supreme Commander of Allied forces in the South-West Pacific Area. He was to direct almost all of Australia’s war effort in the coming years, loyally supported by the Prime Minister, John Curtin.

Photo: General Douglas MacArthur on an inspection tour of the New Guinea Battle Area. AWM 013419.

Five crucial battles dominated the rest of 1942, turning the tide of war in the Pacific.

In May 1942 the Japanese launched a plan to invade Port Moresby, in the Australian territory of Papua. Allied code-breakers enabled a mainly American fleet (but including the cruiser HMAS Australia) to intercept and block it. In the battle, fought in the Coral Sea, north-east of the Queensland coast, the Japanese lost an aircraft carrier, vital for further advances, defeating the invasion attempt. The battle was fought largely by aircraft, the first in which surface ships barely saw each other.

While the Japanese launched minor diversionary raids (including one using three ‘midget’ submarines on Sydney Harbour on the night of 31 May-1 June) they failed to distract Allied commanders, who possessed the vital advantage of being able to read Japanese codes.

In June, code-breakers again gave American commanders the opportunity to lure the Japanese fleet into battle and in the Pacific Ocean, in the battle of Midway, the two sides clashed. Again mostly using carrier-based aircraft, the Americans succeeded in sinking four more Japanese aircraft carriers, effectively ensuring that further Japanese advances were impossible.

Photo: Midway, Pacific Islands, 6 June 1942. The Japanese Cruiser Mikuma on fire and sinking following attacks by US aircraft. AWM 306578.

Allied victory at Kokoda

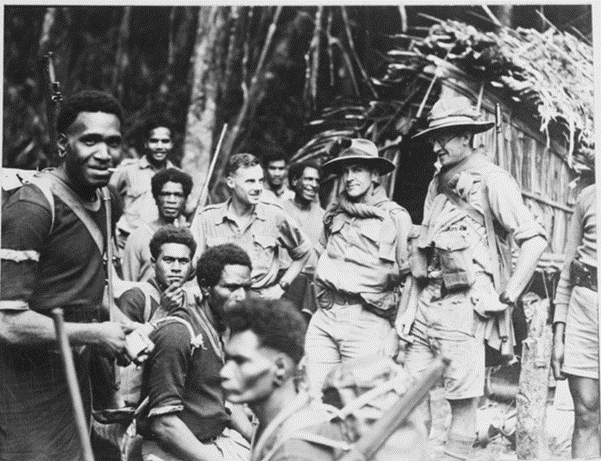

The Japanese, however, continued their offensives in Papua and the Solomon Islands. Prevented by the Coral Sea defeat from landing at Port Moresby, in July Japanese troops landed on the north coast of Papua and advanced over the trail leading south. A small force of Australian citizen soldiers, particularly the Militia 39th Battalion, met them at the village of Kokoda, high in the Owen Stanley Range. Aggressive and more experienced Japanese troops drove the Australians back, and for two months they conducted a fighting retreat, enduring some of the most arduous conditions ever faced by Australians in war, suffering heavy losses. Sustained by Papuan carriers (many of them conscripted) the Militia, later supported by AIF formations rushed to Papua, and learned to fight in the jungle. In September the Japanese, also hampered by the rugged country and at the end of a tenuous supply line, halted on Imita Ridge. When fresh Australian units attacked, they found the Japanese were withdrawing, and the fighting now flowed northwards. After a series of hard-fought actions against determined Japanese resistance, Australian troops re-gained Kokoda early in November. By the year’s end they were attacking Japanese troops dug-in on Papua’s northern coast.

Photo: Kokoda, New Guinea, August 1942. New Guinea native carriers meet Australian officers at a rest spot on the Kokoda Trail. AWM 150655.

Meanwhile, in late August, a Japanese attempt to establish a base at Milne Bay, at the eastern tip of New Guinea failed. An Australian Militia and AIF force, supported by American troops, RAAF fighters and RAN ships, fighting in almost constant rain, defeated the Japanese landing. The battle has been hailed as the first Allied victory against the Japanese since the war’s outbreak.

Finally, from August 1942 to early 1943 the Americans fought a long and costly campaign in the Solomon Islands. Making the first of many amphibious operations, American marines landed on Guadalcanal in August 1942, beginning a campaign in which over 7000 American and 20,000 Japanese died, including a bitter series of naval clashes in which 30 Allied and 38 Japanese ships were sunk. (The ships lost included HMAS Canberra, sunk with 84 dead.) Japanese losses in the Solomons compelled the Japanese to withdraw in Papua and demonstrated the Allies’ growing strength.

By the end of 1942 Allied victories, in the Coral Sea and at Midway, in Papua, at Milne Bay and Kokoda, and in the Solomons, demonstrated that the Japanese had lost the initiative and that the Allies were now ready to embark on the series of offensives which would, over the next three years, bring victory in the Pacific.

Photo: Mountain scenery from Owers Corner showing Imita Ridge and Ioribaiwa Ridge in the background, Owen Stanley Range. AWM 061958.

Postscript

The route over the Owen Stanley Range was and is called both the Kokoda Trail and the Kokoda Track, with ‘trail’ favoured in American usage and ‘track’ used by many Australians. The Australian Army adopted ‘Kokoda Trail’ as a battle honour, but the Australian official history used both ‘track’ and ‘trail’ in different volumes. Rather than argue about which should be preferred, it is better that Australians know what the words mean: one of the most arduous campaigns they have ever fought.